ART

Authenticité – a culture fix that’s not streaming on Netflix

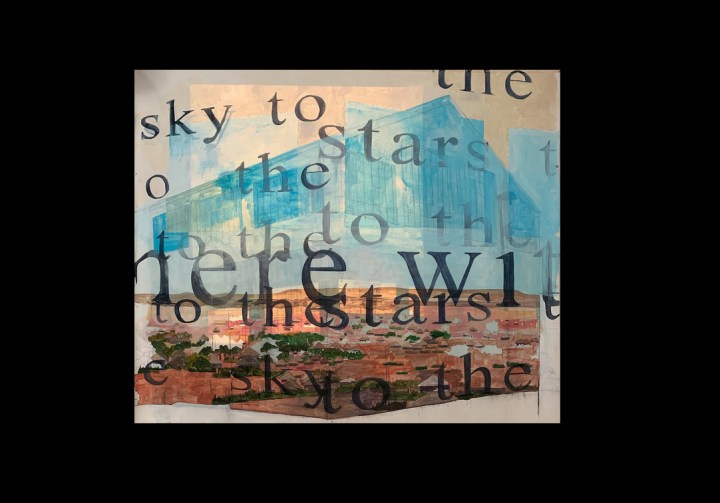

Goodman Gallery’s latest exhibition Authenticité brings post-independence history into digital space, stretching digital possibilities with thoughtful artwork and stories from nine artists from across Africa and the diaspora. Visit the gallery from home for a culture fix that’s not streaming on Netflix.

It has been a while since anyone went to an art gallery. Perhaps you miss the social buzz of openings with free wine. Or is it the white rooms perfectly lit for a photo that says, “I have taste” while showing off a great outfit? Or perhaps it is the actual exhibitions – the art and the ideas that you miss.

Luckily, some of the gallery experience is still available from home as South African galleries and museums shift operations to digital space in light of the ongoing national shutdown. And while there is no free wine and dressing up is up to you, Goodman Gallery’s Authenticité, an online exhibition of nine artists, is live and the artworks in this “viewing room” are worth a visit.

You can optimise the “gallery” experience in a few ways. Go full screen on the computer and really make a thing of it, just for thirty minutes if you can. I had a cup of tea and sat with the curated playlist on in the background. A collection of 20 songs from the post-independence era, the music speaks to the triumph, optimism, uncertainty and grief swelling in the wave of successful decolonisation movements across Africa in the 1950s and 70s. This is the soundtrack of the period the exhibition finds its source material in and provides a welcome accompaniment to the visual content.

Feel free to skip the opening text at first and scroll straight down to the art – it’s a little wordy, and you can always come back later. In brief, Authenticité wrestles with colonial history, a familiar and recurring concern in contemporary African art. The different artworks grapple with national memory from a decidedly 21st-century post-post-independence (if you will) perspective.

All the work in the show was made in the past six years, mostly by artists aged around 40, a bridge generation born in the 1980s that comfortably melds historical and contemporary politics in their work. Their mode of authenticity is a no-nonsense reckoning with the continent’s past to the good and the bad. Historical despots like Rhodes and Mobutu appear along with lesser-known figures like Zimbabwean spiritual leader Sekuru Kaguvi, an everyday Maria in Mozambique, and South African author Bessie Head.

The debate around looted objects in European museums also comes up, including Trevor Noah weighing in problematically from The Daily Show desk as he asks Europe for “a tiny piece of that sweet colonialism money and build a museum in Africa that you feel confident in.” Though Noah’s presence reminds us that these historical wrongs are very much tied up in our daily cultural reality. The exhibition tries to deal with African heritage on multiple levels: intellectual, political and material, and does this largely from a post-colonial perspective, one that places Mobutu Sese Seko as an unsettling centrepiece.

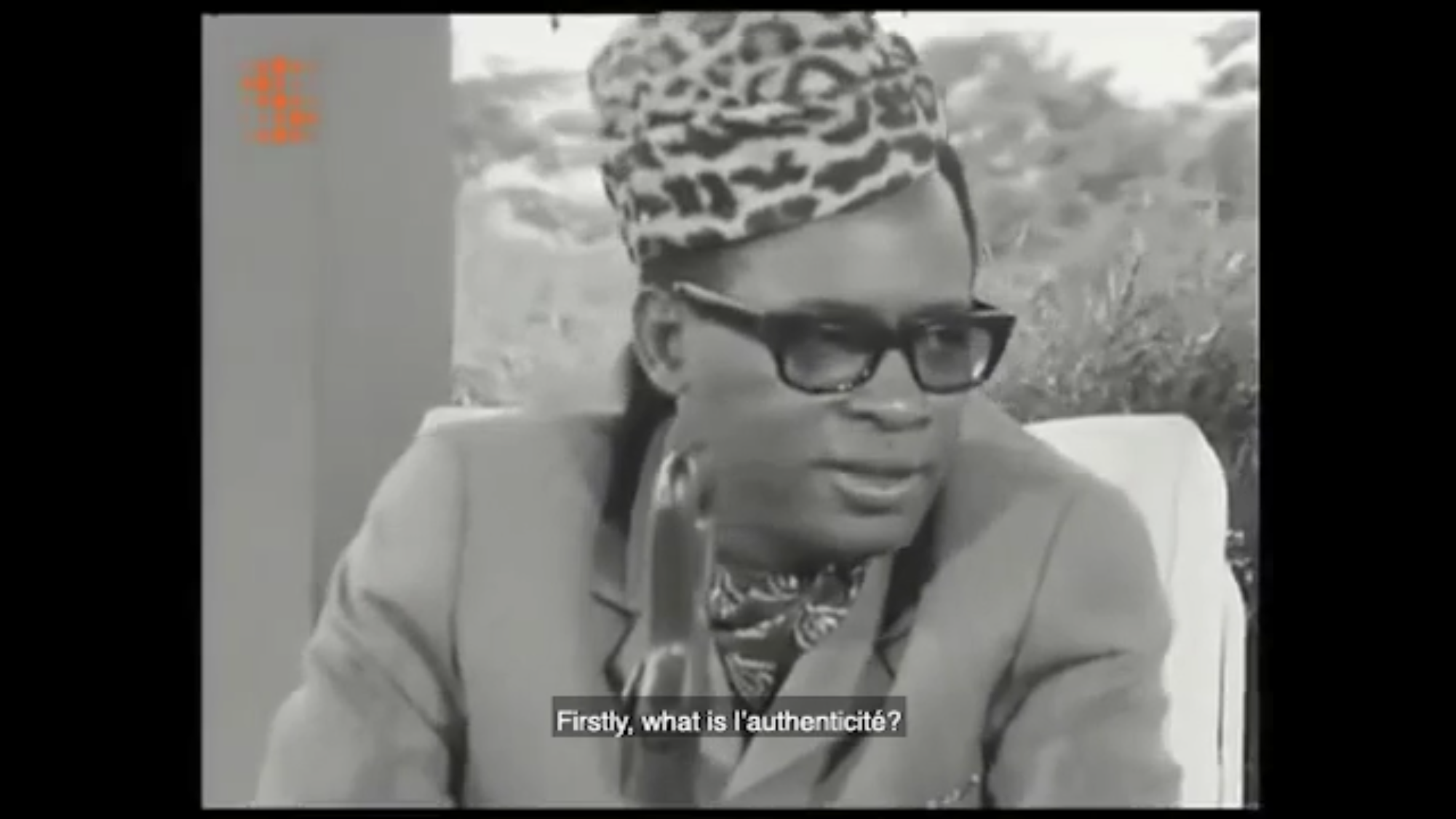

Mobutu Explique ce Qu’est “L’Authenticité” Le 28 Mai 1972 –Uploaded by Nerrati Afrique on 5 March 2013

The exhibition title comes from Mobutu’s concept of Authenticité, a quest for state-sanctioned cultural authenticity. This empowering project involved the total erasure of colonial inheritances like statues and names as well as the repatriation of Zairean art from Belgium. The exhibition features an insightful 10-minute interview with Mobutu on the subject. And while we see his iconic leopard skin cap, little attention is paid to his true signature, the brutal, decades-long dictatorship in what is today the DRC. Described in The Atlantic as “one of the last five-star despots of the Cold War era,” Mobutu gripped power on the basis of fatal violence and corruption for decades, yet the text provided by Goodman barely hints at this, allowing his identity as a cultural theorist to take the fore. At first, this seems insane and irresponsible, but perhaps it is a master-stroke, opening space in the project.

This complication is graphically represented by a sculpture by Cape Town-based Haroon Gunn-Salie, the youngest artist in the show. Part of his 2015 series, Soft Vengeance, two bright red arms stick out of the white gallery wall and are cast from a statue of Cecil John Rhodes at the Iziko South African Museum. The body and head of the notorious colonial figure have vanished, only his blood-red hands remain, a potent symbol of guilt as well as a reference to the defacing of colonial and apartheid-era monuments during the #RhodesMustFall activism.

Haroon Gunn-Salie – Soft Vengeance (Cecil John Rhodes), 2015 Reinforced urethane (Image courtesy of Goodmal Gallery)

Gunn-Salie’s work decontextualises hodes and makes him unrecognisable. Does it make his despicable record unrecognisable too? In erasing the villain do we erase the villainy? Similar questions apply to the narrow representation of Mobutu, forcing us to consider our own power in making history as we decide what to memorialise, forget, or reconstruct, and inevitably lose some authenticity no matter what we choose.

Misheck Masamvu – Prison staircase, 2014 Oil on canvas (Image courtesy of Goodman Gallery)

A stand-out moment comes from Misheck Masamvu, who triumphantly solves these problems. His 2014 painting, Prison Staircase, is a deliberately fictional history that Masamvu claims as fact. A Zimbabwean spiritual leader is modernised as a silver-screen superhero in the picture, glowing green and hovering with a red cape. A voice recording from the artist accompanies the image, Masamvu explaining that Shona elders like Sekuru Kaguvi and Mbuya Nehanda, who appeared to have supernatural powers threatened the colonial order and were fearless of the machinery of the state.

“They could describe a gun as something that the bullets might actually turn into water. They always knew how to empower their community, to look at danger right in the face. That is what Marvel Comics are trying to do—you can be invincible!”

Hearing directly from the artist is part of the authenticity made possible in this viewing room. It activates the artwork beyond the screen. Brief audio and video clips from Pamela Phatismo Sunstrum, Cassi Namoda, and Gunn-Salie put voices and faces behind the material, offering a window into the processes and concepts behind the art. This doesn’t typically happen in the gallery space where work is presented in a polished format.

It is exciting to see Goodman using the online platform to expand the possibilities of what an exhibition can be. On top of music, voice notes and behind-the-scenes footage, the viewing room platform promises a new type of interactivity and researchability, especially as a trip to the gallery is impossible with current stay-at-home orders in place. Most of the works are part of bigger series or projects which deserve attention in their own right, like Kudzanai Chiurai’s drawings that link vintage Nollywood with celebrated African literature. This extends the exhibition further into the internet, taking advantage of the connectivity of the platform.

The gallery is working to draw commercial interest to and from these larger works too, a little blue “Sale enquiries” button hovers next to every piece, using the ease of digital space to profitable ends. There is still opportunity for further development here but the viewing room could become a critical part of the contemporary art landscape if treated seriously and enthusiastically.

There are, of course, some losses in experience that cannot be bridged between the real and the virtual worlds. The last artwork in the show is a stunning structure of eucalyptus leaves by Canadian artist Kapwani Kiwanga. Flowers for Africa: Rwanda literally remakes history as Kiwanga builds a flower arrangement seen in a photograph of Rwandan independence celebrations – she then lets the plants decay, poignantly reflecting on failed ambitions of the era. Here, she produces a towering archway covered in leaves. Sitting at the computer you imagine, regretfully, how the leaves might feel in your hands, how it might dwarf you as you walk underneath, how heady that eucalyptus scent might be.

While digital space has a lot to offer it is not going to be a total replacement for the real life gallery which some may be missing more than others. It’s not supposed to be a one-to-one experience, but a new one. Authenticité is a compelling case for embracing the viewing room and hoping that museums and galleries continue to develop this format post-quarantine, either as a complement to physical exhibitions or as independent projects.

#MuseumFromHome can, after all, still exist when we are allowed outside. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider