CORONAVIRUS & HUMAN RIGHTS

De-densification is just a fancy word for eviction

Are our state authorities using the Covid-19 outbreak as an excuse to justify the forcible eviction of informal settlement residents?

During a press briefing on 24 March 2020, Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation Minister Lindiwe Sisulu announced that the government planned to “de-densify” 29 heavily populated informal settlements in an effort to stop the spread of Covid-19. Since then, five specific settlements were identified as priority areas. According to Sisulu, de-densification is necessary to ensure that families living in densely inhabited informal settlements are able to effectively practice physical distancing.

But what does de-densification actually mean? The Social Justice Coalition (SJC)’s Axolile Notywala explained it best when he said that de-densification “is a fancier word for forced eviction”.

De-densification, as conceived of by the state, means relocating people away from their existing homes to a different location – usually somewhere less well-located with fewer resources.

As Sisulu said: “We will need to urgently move some of our people for the de-densification to be realised. Land parcels to relocate and decant dense communities have been secured”. She added that these relocations were necessary to relocate communities to “healthier and safer homes”.

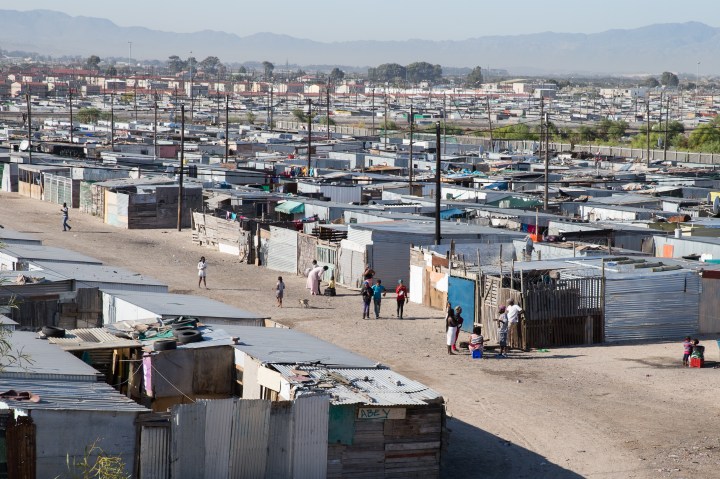

There is no doubt that communities living in informal settlements are particularly vulnerable to the spread of Covid-19 as many informal settlements have limited (if any) access to basic services, including water, electricity and sanitation – a direct consequence of the failures of the post-apartheid government to improve people’s standard of living.

However, Sisulu’s announcement was met with concern by civil society, housing activists and informal settlement residents. They are afraid that the type of accommodation that will be offered to informal settlement residents – rather than “healthier, safer homes” – would more likely be underserviced, government-sanctioned shacks, located in far-flung areas and without adequate access to basic services.

These concerns are not unfounded. This is exactly the kind of accommodation that the government has offered people being evicted or relocated for decades in Cape Town, Johannesburg and Durban.

The government calls these settlements Temporary Relocation Areas (TRAs) or transit camps, but residents refer to them as what they are – “amathini”, “blikkies” or “government shacks”. Kerry Ryan Chance, an anthropology lecturer at Harvard University, has likened them to “human dumping grounds”.

TRAs are “temporary” camps made of tents or corrugated iron dwellings erected by the government to house families who have been displaced as a result of an emergency or eviction. The dwellings are often poorly constructed and fragile. In many respects, these camps are indistinguishable from the corrugated iron shacks that people have been removed from, except for one crucial difference: their location.

TRAs are often located at the margins of urban areas – even further away from economic opportunities, transport routes and social amenities like schools, hospitals, police stations and clinics than the informal settlements from which people have been removed.

As a result of their peripheral location, these camps often have limited or no access to basic services, forcing hundreds of families to collect water from a few communal standpipes and share a small number of outdoor toilets (that are often blocked or broken). In some instances, poor planning has meant that people are relocated to TRAs before the requisite infrastructure for the most basic services is in place.

Many informal settlement residents have resisted evictions and relocations to these areas for decades. However, in the face of a national disaster as a result of the Covid-19 outbreak and with the full institutional force of the state supporting their removal, many will be unable to fight their relocation.

This is not the first time that health concerns have been used to justify removing people from their homes. During the colonial and apartheid eras, the state often violently uprooted whole neighbourhoods of black and coloured households on the basis that their very presence in well-located urban areas threatened the health of the public as a whole.

Laws like the Health Act of 1817, the Slums Act of 1934 and the Health Act of 1977 gave the police far-reaching powers to forcibly relocate black and coloured people. The apparently race-neutral language of these laws masked their insidious impact and the ease with which the colonial and apartheid states could employ them to do the dirty work of racial segregation.

These historical removals raise some deeply concerning questions. Could our state authorities be using the Covid-19 outbreak as an excuse to justify the forcible eviction of informal settlement residents?

In Cape Town, these concerns may be justified. Within a week of Sisulu’s announcement, Western Cape MEC for Human Settlements Tertius Simmers announced that two densely populated informal settlements had been identified for “thinning”, namely Greater Kosovo and DeNoon. Both of these areas had historically been earmarked for relocations by the City – leading some to question whether the City is using the national disaster to more easily push through evictions that it was already planning.

And this isn’t solely an issue in Cape Town. Of the five informal settlements identified by the government for de-densification, three have seen attempted evictions either at the hands of the state or private landowners – DeNoon in the Western Cape, Kennedy Road in KwaZulu-Natal and Mooiplaas in Tshwane. Local politicians have long considered Kennedy Road and DeNoon “problem areas” – probably due to regular community protests and active community resistance. In most of these settlements, attempts at eviction or relocation have been resisted and even challenged in court. Now, however, the already limited ability of informal settlement residents to resist their relocation has been significantly diminished.

Relocating informal settlement residents to accommodation modelled on existing TRAs or transitional housing could have devastating consequences. Research on the impact of TRAs conducted by Ndifuna Ukwazi in 2017 shows that relocations have an incredibly disruptive impact on the fragile social support networks of informal settlement residents – support that is essential during an international health crisis. But more worrying is the dire economic implications that even relatively minor relocations could have as people are cut off from their sources of livelihood or income-generating opportunities and forced to spend more of their earnings travelling to and from work. In the face of the looming international economic fallout in the wake of Covid-19, should we not do everything in our power to protect people’s existing livelihood strategies at all costs? And given that the basic services in TRAs are frequently worse than in existing informal settlements, are these homes really going to be “healthier and safer”?

Perhaps most worrying is that these relocations will not be temporary. Many of the TRAs set up by the government have ended up becoming permanent as residents wait years or even decades to be moved to permanent housing. KwaZulu-Natal Human Settlements MEC Peggy Nkonyeni recently admitted that “many people have been staying [in transit camps] for more than 10 years and if you ask me how their living conditions are… they are very very bad.”

Some TRAs, like the infamous settlements in Blikkiesdorp or Wolwerivier, have become synonymous with government neglect. Mark Hunter, an associate professor at the University of Toronto, has said that residents are “often left in these areas indefinitely without any timeline on when they will be provided permanent accommodation”. At the periphery of the City, they fall off the housing radar and become invisible to those in power.

But Cyril Ramaphosa’s government doesn’t have to repeat the mistakes made by previous governments. It has the opportunity to adopt a more humane, sustainable response to the housing needs of informal settlements while also doing everything in its power to slow the spread of Covid-19. One option, suggested by the Cape Town Community Action Network (CAN), is to utilise existing public facilities to house informal settlement residents temporarily during the crisis.

If certain informal settlements need to be “de-densified” to help with social distancing, then why not move those residents into hotels like the UK government plans on doing? Or move residents to sports stadiums and schools with boarding facilities? Using these kinds of existing, well-located facilities that are already equipped with running water and adequate sanitation would ensure the temporary housing is both healthier and safer, and that it is in fact temporary. After the crisis, residents would be allowed to return to their homes because they cannot just be left in public facilities the way they could be dumped on the outskirts of the city. Another option would be to offer residents tenure security on well-located public land rather than peripheral areas.

In the 1870s Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx’s collaborator on the Analysis of Capitalism, documented the horrific housing conditions of the working classes in industrial cities in England. Engels wrote that the bourgeoisie has no method for settling the housing question other than moving it around. In a poignant passage, he wrote:

“[S]candalous alleys and lanes disappear to the accompaniment of lavish self-praise from the bourgeoisie on account of this tremendous success, but they appear again immediately somewhere else…”

More than 150 years later, our governments and elites have still found no better way of dealing with the housing needs of the poor and working-class other than to move them to a place where they are invisibilised – at least until the next crisis comes along.

“For billions across the world, and for us here in South Africa,” Ramaphosa said in his national address on 9 April 2020, “the coronavirus pandemic has changed everything. We can no longer work in the way we have before”.

Our government recognises that we need to adapt to a new reality. And this demands that we protect and house the vulnerable in a dignified way. DM

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider