MAVERICK LIFE ART

No space for distancing

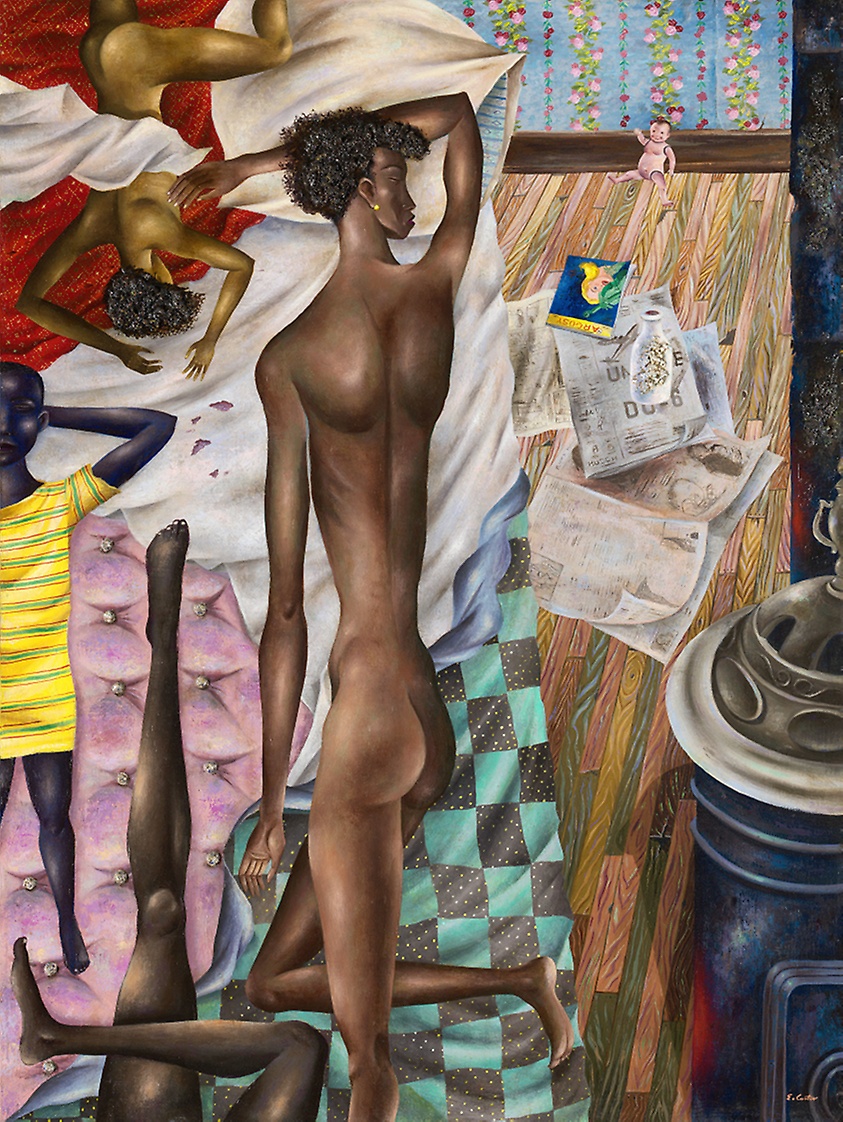

Eldzier Cortor painted his The Room No. VI in 1948. Now, 72 years later, this work of art resonates deeper than ever with viewers.

Eldzier Cortor’s The Room No. VI is overwhelmingly crowded. A messy bed, really a jumble of tangled sheets and bodies, fills the left half of the painting. Newspapers, magazines and a milk bottle are scattered across the floorboards to the right, a potbelly stove peeks in at the edge while a little baby doll smiles unclothed against the wall, limbs splayed in all directions.

Eldzier Cortor. The Room No. VI, 1948. Through prior acquisition of Friends of American Art and Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison; through prior gift of the George F. Harding Collection. © Eldzier Cortor (Image: The Art Institute Chicago)

Almost every inch of the painting is busy with bold patterns and colours, making it hard for the eyes to settle on any one part. A blanket is checker-boarded with sea-green and yellow-spotted grey squares; a rosy peach-pink mattress is stippled with grainy circles flanked with dark, curving lines; a scarlet sheet is delicately crisscrossed in dashes of gold; one figure wears a vibrant yellow nightgown striped with green and red; and bars of soft blue patterned with diamonds peep out of a pillowcase. Even the floorboards — a grid of swirling ochre, pine, coral and baby blue — are as vivid as the floral wallpaper in bright spring tones. The painting moves and pulses with colour, it gives you a headache if you look at it for too long. It might even be why its occupants have closed their eyes.

Four figures, black women and girls, sleep on the bed. Their long bodies bend to fit together like puzzle pieces, filling all available space: a crooked arm accommodates an outstretched leg, a foot slots between ankles. Each person is rendered in a different tone, alluding to diversity among African-Americans, ranging across deep purple, cocoa and copper. Their bare skin shines as if sweaty, highlights accentuating the curves of slim thighs, calves, backs and bottoms. There is something strangely urgent about their rest. It seems as if they are trying to sleep rather than snoozing easily. The little room seems hot and claustrophobic, escapable only in slumber, the only respite from the cramped conditions.

American contemporary artist Eldzier Cortor painted this picture in a Harlem hotel room in 1948 and brought it back to his home on the South Side of Chicago on a Greyhound bus. The nude figures, one of the artist’s staples, aroused a certain excitement on the journey back but his painting is far from erotic. He was capturing life on the South Side as he remembered it; specifically, life in a compact kitchenette apartment.

Larger houses and apartments were converted by white property owners into multiple single-room units, divided by cheap beaverboard walls and rented on a weekly basis to the influx of poor African-Americans who migrated to Chicago in the first half of the 20th century, fleeing racial violence in the south for economic and social prospects in the north. Whole families were housed in single rooms and shared inadequate kitchens and bathrooms with others in the building. Cortor’s own family was part of the Great Migration, moving from Richmond, Virginia (the formal capital of the pro-slavery Confederacy), to Chicago in 1918 when Eldzier was just a year old.

“At that time Chicago was a swinging place,” he recalled in an interview for BOMB’s Oral History project.

Life in the derogatorily named “Black Belt” was indeed swinging. Though economically and socially isolated from the rest of the city, African-Americans flourished as best they could in the new urban environment, developing an independently thriving community with its own businesses, institutions and a whole lot of culture. The Black Belt soon transformed into the “Black Metropolis”, centred in the historic Bronzeville neighbourhood, home of a cultural renaissance akin to Harlem in the 1920s and Sophiatown in the 1940s.

Here, jazz greats like Louis Armstrong, Nat King Cole and Dinah Washington performed at the iconic Regal Theater. The Chicago Defender, “far and away the most important publication in the coloured press”, built its headquarters on Grand Boulevard (today Dr Martin Luther King Jr Drive). Canonical artists like Elizabeth Catlett and Margaret Burroughs all lived and worked there, as did renowned poet Gwendolyn Brooks who memorialised the neighbourhood in her writing, even including a meditation on the kitchenette building in her 1945 A Street in Bronzeville collection of poems.

“We are things of dry hours and the involuntary plan,

Grayed in and gray. ‘Dream’ makes a giddy sound, not strong

Like ‘rent’, ‘feeding a wife’, ‘satisfying a man’.”

Cortor came of age in this dynamic yet trying environment. In art classes at Englewood High School, with classmate Charles White, he would visit the Art Institute of Chicago to study Western masters across the eras. Though he dropped out of high school to work and support his family, he later completed his education at the museum’s prestigious art school and today is well-represented in the collection alongside some of the Western masters like Jacques Louis David, George Seurat and Thomas Hart Benton, who he credits as major influences. Like these painters before him, Cortor’s work has strong social motifs, commenting on the conditions of black life as he experienced them in Chicago and the southern states. He rarely painted from life, preferring to construct images from memory and imagination, allowing him to make multiple references in single works.

In The Room No. VI, the finely modelled features of the nude women are inspired by African sculptures seen at the Field Museum of Natural History, marking a link to his people’s heritage. The papers on the floor represent real publications familiar to him from childhood like the weekly pulp fiction magazine Argosy and what are likely copies of the Defender.

“Those are real things from my memory as a kid that I hold onto; that are precious to me,” he says of his use of memorabilia.

Precious or not, the memory of the kitchenette apartment was definitely vivid for Cortor. Cramped and claustrophobic spaces recur in his work from the late 1940s, in paintings like The Room No. V and Lady Knitting, both occupied by women who he resolutely affords dignity in spite of their inadequate surroundings. Cortor believed that African-American women represented the continuation of the race, a source of eternal renewal for black life. In his paintings, women are markers of strength and hope to counter the difficult conditions they are represented in.

Looking in today’s context, 70 years after the work was painted, a new set of concerns arises. Though Cortor could not have anticipated this, his interior scene immediately brings to mind the stay-at-home and social distancing orders being issued around the world as the threat of the coronavirus pandemic looms large.

This work with its tightly packed figures contending with limited space is particularly tense. First, one considers the disproportional impact of the virus among African-Americans concentrated on Chicago’s South Side today where black people make up about 70% of Covid-19 deaths despite constituting 30% of the city’s population.

Similarly distressing figures are being reported in Michigan, Louisiana, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Black Americans are more likely to work in essential service jobs and positions without sick pay, live with pre-existing conditions like diabetes and asthma as a result of environmental and economic conditions, and receive poorer quality healthcare. The virus has thrown these racial disparities into sharp relief in a fatal way.

Though the US is the current global leader in Covid-19 cases, racial and socioeconomic disparities in South Africa also mean that the poorest will be the hardest hit by the virus.

“If it touches down here, or in any township, it’s game over,” says Kayamandi resident Vusi Mokoena in Daily Maverick, aware of the profound risks facing those living in densely populated townships. The New York Times reports that at least 15% of the population, some four million people, live in informal urban settlements where there are “five or six or even more to a tiny, unventilated corrugated shack”.

Immuno-compromised populations with high rates of HIV, TB and malnutrition, who have no choice but to share limited resources like toilets and water taps and cannot afford the luxuries of stockpiling food or working-from-home are almost totally helpless to contain the spread of the virus. Further, the economic knock-on effect of the national shutdown, extended last week, will only exacerbate the dire poverty already experienced by millions of South Africans.

“In these environments, staying home itself can be a risk,” reports the Mail & Guardian. Unfortunately, disempowered black people around the world have little choice in the matter, whether in the 1940s or today.

Looking closely at this painting, we can consider some of the most vulnerable members of our societies across history without losing sight of their humanity, dignity and resilience. Black lives are not statistics and will never be disposable. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider