CORONAVIRUS OP-ED

Covid-19 opens a window of opportunity to roll out mass testing for other diseases

Mass screening and testing could be as comprehensive as possible by offering a concoction of screening for TB, HIV and other underlying medical conditions. In that way, we will help to prevent the deaths of those with the underlying disease who may get Covid-19 in the future.

South Africa has been hit by Covid-19 on top of a quadruple burden: infectious diseases like TB and HIV; chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension and mental illnesses; malnutrition, maternal and childhood diseases; and violence, including gender-based violence.

Emily Wong from the Africa Health Research Institute in KwaZulu-Natal has highlighted the “colliding epidemics” of TB, HIV and Covid-19 in South Africa and the higher risk of severe disease in these patients, especially if the disease is not controlled by treatment.

Even though South Africa has one of the biggest antiretroviral (ARV) programmes, we still have about 2.5 million HIV-positive people who are not on ARVs and thus potentially at high risk. What could count in our favour is that our population profile is much younger than countries like Italy and UK that have been hard hit by Covid-19. We know that the fatality rate in those aged over 60 years increases exponentially by age and is exacerbated by underlying medical conditions. The fatality rate for those aged over 80 years is 14.8% compared to a 3.4% average fatality rate for all age groups.

Countries with more resourced health systems and healthier populations than South Africa are grappling to cope with the impact of Covid-19 on their health systems. In South Africa, Covid-19 puts additional pressure on our already under-resourced and overstretched public health system.

There are already concerns that some provinces are restricting normal primary health care services such as sexual reproductive health services and prioritising maternal and emergency services.

We argue that, on the contrary, this “colliding of epidemics” calls for a comprehensive response that includes the very necessary public health interventions of identifying those with Covid-19 and their contacts, and managing them and ensuring that we manage our current burden of disease instead of falling yet again into the default fault lines of verticalisation.

What measures has SA put in place to address Covid-19?

The South African government, like many African countries, is taking drastic steps to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic by putting in place globally recommended public health measures to slow down or delay the spread of the virus and to provide an economic and social safety net for its citizens.

Researchers from the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford University have developed a country stringency index (0-100) to the response to Covid-19. This scores the stringency of countries’ responses to the pandemic and assesses the impact of these on the pandemic. South Africa is one of the 77 countries in their first publication and was in a group of countries whose index was 80-100, meaning that we have some of the most stringent measures.

Of course, this index says little about how well these measures are adapted for the local context, how these measures are responsive to the needs of citizens, especially those who are poor and marginalised, how impactful these measures will be in the long run and what unintended consequences they will have, especially in poor and marginalised groups.

Reports from the US have highlighted the disproportionate impact this disease will have on the poor. In Chicago, the African-American population accounted for 70% of all Covid-19 cases in the city and 50% of cases in the state, despite this group making up only 30% of the population. This is due to overcrowding in urban areas and this group working in essential industries and thus not able to stay at home.

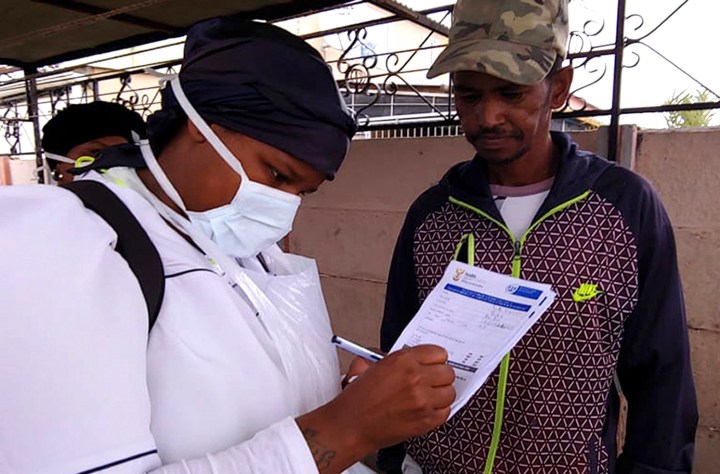

President Cyril Ramaphosa announced the rolling out of Covid-19 community screening door-to-door starting this past week using a social vulnerability index to target the most vulnerable communities. We know that mass testing was part of the successes seen in China and South Korea. In South Korea there was rapid scaling of testing to 5,500 tests for every one million people. Tests were readily available, free with doctors’ prescriptions, available publicly and privately, drive-through services were provided, and there was contact tracing with targeted testing of contacts and monitoring of infected persons, supported by technology with a government app.

South Africa is planning to increase testing capacity by using Gene-Expert technology and mobile technology for contact tracing.

So what is the problem?

While we welcome the proposed testing measures, we think South Africans need to reflect on lessons from the HIV and Ebola responses in particular. The recent article by Nathan Geffen on “How many people could die of Covid-19 in South Africa?” in GroundUp quoted work from researchers projecting that we could see 94,835 to 239,610 deaths in South Africa per year due to Covid-19. He reminds us that we have been here before in 2005 where 285,000 died from AIDS. We have learnt from large-scale testing for HIV that this works best when it’s done comprehensively.

We know that there are many in South Africa living with HIV/TB/mental illness/gender-based violence/chronic diseases. We have learnt that it does not serve us to verticalise. Not only does it not allow us to provide person-centred care, but it brings with it immense stigma.

South Africa has been practising comprehensive screening and testing for some time now. We believe that this is not the time to abandon that strategy, which was crafted through many years of experience. We do not need to repeat the mistakes of the past. When epidemics strike, fear, anxiety and despair can be agonising. We saw this during Liberia’s Ebola epidemic and in the HIV epidemic.

Things we think could be considered

Health Minister Zweli Mkhize has publicly said that he thinks between 60-70% of us will get this disease and that most people will have mild symptoms. However, those who are older and have underlying conditions will have severe illness that could lead to death. All that the lockdown measures are doing is to flatten the curve so that we can buy ourselves some time to prepare the health system and, hopefully, find a cure or a vaccine in about 18 months’ time, if we are lucky.

We could test for Covid-19, pat ourselves on the back, and count the number of people who do not have the disease and see that as a victory. Alternatively, we can also make sure that we use this crisis to catalyse our efforts to find people who are HIV-positive, have active TB, uncontrolled diabetes and hypertension who are not on treatment and link them to care.

Mass screening and testing in the South African context could be as comprehensive as possible by offering a concoction of screening for TB, HIV and other underlying medical conditions. In that way we help to prevent the deaths of those with underlying disease who may get Covid-19 in the future. Furthermore, this will address stigma, as people will know that there is a mass health screening and linkage to care.

We could maximise the use of the data centre at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) by integrating it with USSD technology or other technologies to screen people in SA for the coronavirus, HIV and TB and underlying medical risks. This will allow us to prepare them for the high likelihood that they will get the virus at some point in the near future. Our door-to-door measures could be targeted at those we think require a test for Covid-19, and when positive we should support them to self-isolate, find their contacts and medically manage and monitor those affected, offering rights literacy, engaging in discussions about primary violence prevention, and distributing chronic medication.

Moreover, during lockdown we have captive audiences of population groups we often struggle to reach. We are likely to find more men than usual at home and at designated essential services workplaces. Young people also often respond well to solutions that use technology, especially if these also provide useful information back to them to increase their agency to practise health-promoting behaviours.

We could be using medical and other health sciences students to help look at health records of all our known patients with serious comorbid diseases. We could ensure people have access to their medication, are in conditions where they can practise physical distancing, monitor them and ensure quick access to health services and other social services if required.

This comprehensive response will require a South African multi-sectoral response, including civic organisations, to reach all communities. State security forces could also support these health responses and not just be assigned military tasks. We must, however, innovate on creating community-based models of care that will allow us to increase treatment of HIV, TB, diabetes and hypertension quickly.

Even though we understand that health workers are overstretched now with the current crisis, we must realise that this is just like one finger on a leaking bucket. If we want to seal the bucket, we must find all those who have underlying conditions and make sure they receive care before they contract Covid-19.

We must refuse to be defined by the conditions we face, no matter how depressing they seem – we should choose to be defined by our response. We must plan for the aftermath and the societal rebuilding period for communities most affected by Covid-19. What we do can leave a lasting legacy in the building of resilience in our health response and ensure agency in our people. MC

Vuyiseka Dubula-Majola is the director of the Africa Centre for HIV/AIDS Management at Stellenbosch University and is the former general secretary of the Treatment Action Campaign.

Tracey Naledi is a public health specialist and the former chief director of Health Programmes in the Western Cape Department of Health and a PhD candidate at the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider