A Tribute

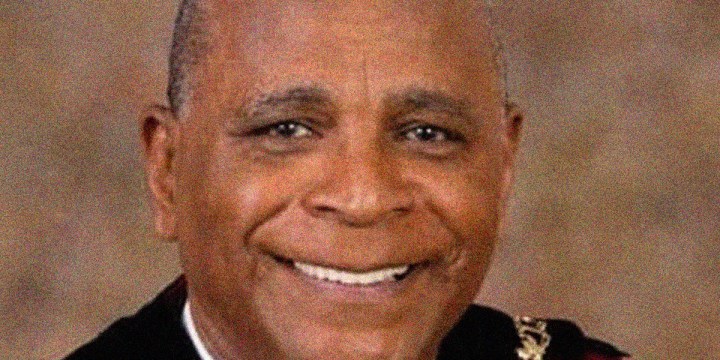

Conrad Sidego (1946-2020), a true brother

Conrad Sidego who died last week was no ordinary acquaintance of mine. He was an older brother, over the years he looked out for me and, by virtue of age, had the authority – with my mother’s blessing – to pull me into line when required. Respect flowed both ways but arched upwards.

Conrad Sidego was upset– possibly angry – with me. His wife Amy probably remembers his true reaction. It was sometime towards the end of 1994 that Frederick van Zyl Slabbert and Alex Boraine took me to Norway, Sweden and Denmark, as an introduction to the key donor personalities that so generously funded the Institute for a Democratic Alternative for South Africa (Idasa), an organisation I took over from Boraine as executive director in August of that year. Conrad was South Africa’s Ambassador to Denmark, based in Copenhagen, and we never paid him a courtesy visit.

I suppose it was an understandable habit inherited from the apartheid past, where visiting a representative of a government that we despised and opposed was unthinkable. But Conrad represented the transition from FW de Klerk to Nelson Mandela and was no apartheid apologist. De Klerk appointed him as the first person of colour to represent a country in transition to democracy.

Still, a visit to Conrad and Amy was not on our schedule. After our formal business was done my eldest daughter Gabby became violently ill from soured milk inadvertently provided by a kind young man at our hotel and we spent the rest of our short time there focused on nursing her back to health.

I tell this story because Conrad Sidego who passed away last week was no ordinary acquaintance of mine. I first met him sometime in the mid-1960s when he (and later his sister Daisy) joined Hewat Training College in Athlone as student teachers. My parents, Pat and Shelma James, were the house parents of the student residence. My father was the woodwork master at Hewat and my mother gave up her primary school job to look after the 65 students placed in their care. Jakes Gerwel, appointed to teach Afrikaans language and literature at Hewat, joined the residence as an assistant to my father and became part of what, in time, became a close and durable extended family.

Conrad Sidego arrived at Hewat, the striking figure that he was, truly tall, dark and handsome. He was from the beautiful town of Tulbagh (flattened by the September 1969 earthquake), spoke a delicate Afrikaans, was religious without being pious, had a hearty irrepressible sense of humour, and was friendly, charming and just plain decent a human being.

He came from a large, poor and clearly talented family in an era when rural coloured people’s greatest aspiration was to have their children excel educationally and retain their conservative cultural values and religious mores. Conrad also had obvious leadership qualities and was a clear choice for head boy, appointed instantaneously by my father.

Seven years my senior, Conrad was and remained, much like the late Jakes Gerwel, an older brother to me. Over the years he looked out for me and, by virtue of age, had the authority – with my mother’s blessing – to pull me into line when required. As with all older brothers, whether biological or not, the younger sibling typically had to go to them rather than them come to you. Respect flowed both ways but arched upwards.

So, I was surprised to have a call out of the blue from Conrad sometime in 2011. Helen Zille had asked him to run as the Democratic Alliance’s mayoral candidate in Stellenbosch. I was Federal Congress chairman of the party – an honorary position, really – at the time and he had some questions.

Conrad had a great deal of experience in the world of journalism, corporate communication, management and, most recently, diplomacy. He was also a people’s person and at ease with ordinary folk. He understood poverty and had an authentic feel for the daily struggles of brown and black people. But he had no experience with party politics nor did he understand the political culture of the DA, which he was about to join as a member.

What was the political culture – the formal and informal anthropology – of the DA like, he wondered? What was it like to work with Helen Zille, he probed? Were coloured people respected in the DA, he asked? I had a lot to share with him and we spent many hours over tea in discussion.

In Stellenbosch, Conrad had a real opportunity. It is South Africa’s second oldest formal town of the colonial era. It is a gem of a place situated in one of the world’s most breathtakingly beautiful geographical settings anywhere. At its heart was a decent university that carefully navigated its transition from being an Afrikaner nationalist think tank to serving the nation. Situated in the heart of a successful agricultural economy – grapes, wine and fruit – it was surrounded by a research and innovation infrastructure that, if leveraged with major investments, could turn Stellenbosch into a South African University of California at Davis, Cornell University at Ithaca, Wageningen at Wageningen, Netherlands, or the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences at Uppsala.

Getting there would cost money and much besides. It required a cohesive town and a people who benefitted from a thriving knowledge economy.

Stellenbosch was a deeply divided town by race. The historian Hermann Giliomee documented how apartheid brutalised its coloured residents (Nog altyd hier gewees, 2007) including my grandmother Deborah Newman who with her family and friends were removed like pieces of dirt from the centre of town. My mother’s sister Josephine, beautiful and dark-skinned, took her opera lessons from a Stellenbosch University diva who insisted she enter and exit her house through the back door. Black people were not tolerated in the area, except for the descendants of the Mozambican slaves (called the Mozbiekers) brought to the neighbouring town of Pniel (where my grandfather Pieter James was born) and who were absorbed into the coloured community. Stellenbosch has never reckoned with its deeper history of slavery.

Conrad attended Luckhoff High School in Stellenbosch when apartheid was being elaborated there and understood its history. Today, the racial demography is profoundly different, yet Stellenbosch remains extensively segregated and unequal, and Conrad understood that too. He worked hard to bring the world of the historically excluded together with the extraordinary wealth of the Afrikaner elite who resided there.

He had to help solve the problems of the university, the most compelling of which was as basic as the shortage of parking bays. Most of all, he had to attract a scale of public and private investments to upscale the housing and public transport systems desperately needed and develop the modern digital backbone to power the local economy and the town’s promising science and technology park. Conrad spent the last years of his working life starting an ambitious project that will take many more years to fulfil.

Historical legacies are cumulative and Conrad Sidego’s started at Hewat Training College. It was there that his gift as a communicator was recognised. His training as a teacher was valuable, but it never became his vocation, journalism did.

He was political but not doctrinaire. He didn’t take sides in the heated ideological battles in the coloured community, ranging from the Trotskyist left to the reformist right, opting like a good journalist to report on the debates. He wasn’t sectionalist, but he also was a strong voice for the concerns of the coloured community. The last time I saw him was June 2017 when he wished me well with finding, as he put it, “some breathing space” in the US.

Conrad shared a birth date with my wife Delecia and our phones retained their reciprocal wishes exchanged over many many years. We will miss him greatly and send his wife Amy and children Jonathan, C-J and Bibi our greatest sympathy. DM

Dr Wilmot James teaches at Columbia University in New York City and is a former Federal Congress chairperson of the DA. He is in self-quarantine in New York City, his “breathing space” a necessary prison.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider