CORONAVIRUS: OP-ED

The science and policy behind SA’s new mask recommendations

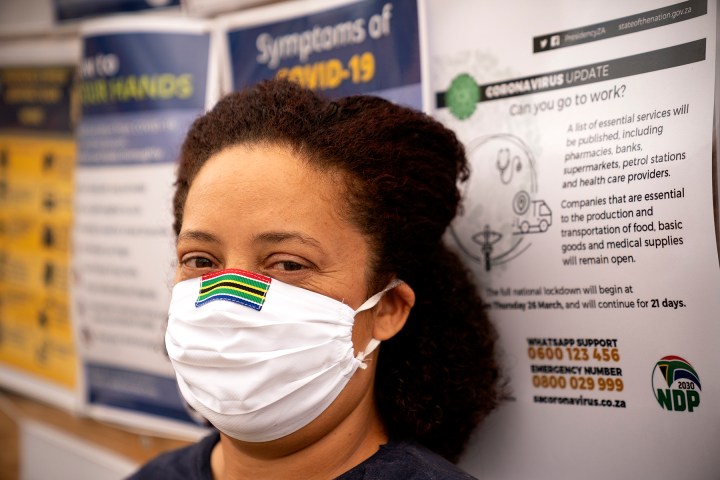

Health Minister Dr Zweli Mkhize recommended last Friday that members of the public wear cloth face masks consisting of at least three layers. This, for the first time, gave direction on an issue that was creating much uncertainty. Dr Kerrin Begg unpacks the reasons for this decision.

The question as to whether members of the public should be wearing face masks during the coronavirus pandemic has been hotly debated globally, with experts expressing divergent views. Countries and authorities have given conflicting advice, ranging from “avoid wearing masks for people who are well”, across the spectrum of “use cautiously”, to advocating widespread face mask use for the general population.

In South Africa, the messaging has until now been consistent with the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendation that the only people who need to wear masks, outside a healthcare setting, were people who were ill or those who were treating them.

A flurry of confusion arose when transport regulations issued under the Disaster Management Act required passengers using public transport to wear masks. A policy guideline was subsequently issued on 2 April by the Western Cape Department of Health, indicating that as the pandemic unfolds, the wider use of masks is indicated even for people who are not ill, especially if they move around in public. And finally, on 10 April the National Department of Health recommended the widespread use of cloth masks.

What are the issues under debate?

Arguments against mass mask use:

- We need to save valuable face masks for health professionals, especially given global shortages of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

- People don’t use them properly, either leaving their nose uncovered, or touching the mask during use or removal, thereby risking transfer of the virus to hands, eyes, nose and surfaces.

- People find them uncomfortable and thus don’t wear them most of the time.

- Inappropriate disposal may cause harm, as moist and unwashed masks containing Sars-Cov-2 may become a vector for transmission.

- Used too early in the epidemic, the wearing of masks may result in compliance fatigue at later high prevalence levels, when it may be of greatest benefit.

- Stigma may be associated with mask use, either because in the eyes of some it identifies the wearer as contagious or as a hoarder.

- Masks provide inadequate protection for the wearer especially without eye protection.

- Face masks provide a false sense of security, so wearers may reduce other measures, like hand-washing and social distancing, and end up taking more risks.

Similarly, there are also arguments for the universal use of face masks

- Any additional, even partial, reduction of transmission would be advantageous to slowing the pandemic.

- Used in combination with other measures, masks can assist to “flatten the curve” and reduce the speed at which the virus spreads.

- Face masks may provide protection where physical distancing is not possible due to socio-economic circumstances, such as in informal settlements, and where hand-washing is difficult due to inadequate water supply and sanitation.

- Masks may protect against asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic transmission, a concerning trend noted in recent weeks.

- Masks may act as a symbol of hope, shared responsibility and collective action to a life-altering pandemic.

Understanding Covid-19 and how masks might help stop the spread

Covid-19 is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus and spreads from person-to-person through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes, and from touching contaminated surfaces. Reducing transmission therefore revolves around preventing person-to-person spread by avoiding close contact (physical distancing), and using infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, including hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) such as face masks.

Droplets sprayed during coughing, sneezing or exhaling can be blocked by a face mask, to a greater or lesser degree dependent on the type of mask worn.

Face masks are critical in healthcare settings to protect healthcare workers from becoming infected when treating known and unknown cases. Knowing that PPE, including face masks, helps protect healthcare workers, it appears a logical next step to promote the wearing of masks in community settings to prevent transmission in the general population. But does it work at a population level?

Extrapolating from healthcare worker protection, the assumption is that “my mask protects me”, in other words, the wearer is protected from being infected by a positive case. Whereas it is in fact more likely that the greatest benefit, as a public health measure, is that “my mask protects you, your mask protects me”, in other words, the wearer is taking the precaution that they may be positive and ensuring that they do not spread it to others.

What does the science say?

Limited evidence is available about Covid-19 and public health prevention measures given that the epidemic is only 100 days old globally. We therefore use scientific evidence of similar viruses and illnesses such as influenza to guide us.

The evidence for “my mask protects me”:

- In the laboratory setting, all types of masks reduced aerosol exposure to a simulated infectious agent, with N95 respirators more efficient than surgical masks, which were more efficient than homemade masks.

- In the community setting, three cluster randomised trials evaluated the effectiveness of medical masks versus no masks for protecting wearers from acquiring influenza-like infection. Together these trials provide evidence of low certainty that medical masks may reduce the chance of infection by 8% compared to no masks.

The evidence for “my mask protects you, your mask protects me”:

- In the laboratory setting, a recent study involving 246 patients demonstrated that face masks significantly reduced the detection of Sars-CoV-2 in the exhaled breath of Covid-19 patients.

- In the household setting, four cluster trials (see information on trials at end of article) evaluated the effectiveness of medical masks versus no masks for protecting household members from acquiring infection from a household member who was ill with confirmed influenza-like illness. Together, these trials provide low certainty evidence that medical masks may reduce the chance of infection by 12% compared to no masks.

In summary, there is low certainty evidence that using face masks may reduce the chance of infection and therefore community transmission.

Translating science into policy

When making policy recommendations to use or not use an intervention, decision-makers need to consider the trade-offs between benefits and harms presented by the scientific evidence, the certainty of the evidence, as well as factors such as values and preferences, resource implications, equity, acceptability, and feasibility.

Importantly, policy-makers need to focus on the desired outcome. In the case of Covid-19, if the goal is to “flatten the curve” as opposed to eradicating the virus, then partial protection afforded by face masks may be sufficient, despite low certainty evidence.

Applying the precautionary principle (a strategy for approaching issues of potential harm when extensive scientific knowledge on the matter is lacking), may be the route to follow particularly with such a serious illness as Covid-19 with no known treatment or vaccine, spreading in an immune naive population, with deaths rising steeply, and health systems under strain.

So, implementing mask-wearing could assist with “flattening the curve” when used in combination with other measures known to reduce transmission, isolation for individuals who are confirmed Covid-19 positive, quarantine for contacts of individuals who are confirmed positive, hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene and physical distancing.

Translating policy into practice

Applying the same precautionary principle relating to potential harms, face mask usage should be accompanied by strictly adhering to safe use guidelines. Such guidelines should encompass obtaining, donning (putting on), doffing (taking off), not touching your face or mask while wearing, cleaning, disinfecting and disposal of the mask.

In other words, “Mask+Message” must be the essence of any implementation campaign.

It would be imperative to ensure that the “golden rules” of infection prevention and control are emphasised alongside mask-wearing.

- Hand hygiene (regular hand-washing with soap and water for 20 seconds);

- Respiratory hygiene (sneeze and cough into your bent elbow, and away from other people);

- Physical distancing (no physical contact, remain two metres away from other people);

- Reduction in gathering and congregation of people;

- Disinfecting and sanitisation of surfaces.

An important caveat is that face masks are critical in healthcare settings to protect healthcare workers from becoming infected. Given that the pandemic has led to a global shortage of PPE, including face masks and N95 respirators, these must be prioritised for healthcare workers. Homemade or cloth masks have therefore been suggested as a stop-gap in community settings in order to save medical face masks for use by healthcare workers.

Looking ahead

As we look ahead towards the end of lockdown, other measures to reduce transmission will be key. Widespread use of face masks may well be an important component of interventions to continue “flattening the curve” and mitigate the inevitable tsunami of Covid-19 cases. Masks may also serve as a symbol of hope, shared responsibility and collective action in the face of a life-altering pandemic.

Dr Kerrin Begg is a Public Health Medicine Specialist at Stellenbosch University.

This article was produced for Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest. Like what you’re reading? Sign up for the Spotlight newsletter and stay informed.

The four cluster trials:

- MacIntyre CR, Zhang Y, Chughtai AA, et al. Cluster randomised controlled trial to examine medical mask use as source control for people with respiratory illness. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012330. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016- 012330

- Suess T, Remschmidt C, Schink SB, Schweiger B, Nitsche A, Schroeder K, Doellinger J, Milde J, Haas W, Koehler I, Krause G, Buchholz U. 2012. The role of face masks and hand hygiene in the prevention of influenza transmission in households: results from a cluster randomised trial; Berlin, Germany, 2009-2011. BMC Infectious Diseases 2012, 12:26. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/12/26

- Canini L, Andre´oletti L, Ferrari P, D’Angelo R, Blanchon T, et al. (2010) Surgical Mask to Prevent Influenza Transmission in Households: A Cluster Randomised Trial. PLoS ONE 5(11): e13998. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013998

- MacIntyre CR, Cauchemez S, Dwyer DE, Seale H, Cheung P, Browne G, Fasher M, Wood J, Gao Z, Booy R, Ferguson N. 2009. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15(2):233-241. DOI: 10.3201/eid1502.081167

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider