BUSINESS MAVERICK: OP-ED

Eskom pension fund is feasting off a captive audience

The Eskom Pension and Provident Fund has 2,376 so-called ‘deferred members’, people who retired before big changes were made to SA’s pension fund environment. But the fund’s rules prohibit former Eskom employees from moving their savings elsewhere.

When Allan Bruce (not his real name), resigned on 18 January 1999 after working at Eskom for 12.5 years, he was given limited choice both in terms of the law and of the fund’s own rules on what he was allowed to do with his pension fund benefits that were vested with the Eskom Pension and Provident Fund (EPPF).

He could either withdraw his own contributions (those not made by his employer), at a compounded interest rate of 3%, which would amount to R109,000 at the time, minus taxes. He would therefore realise R89,000 or leave the collective contributions of both himself and his employer in the fund, which was valued at R461,255 at the time.

The choice seemed obvious. Accepting only a fifth of what he had accumulated over the years was ludicrous at best, so he elected to leave the money there. The fact that the fund was performing relatively well in terms of investment returns at the time provided some comfort.

The pension fund laws changed in 2001, which allowed people to move their money, on resignation, to a deferred (pension preservation) fund of their choice until they retire. It was not applied retrospectively though.

It was called the Pension Funds Second Amendment Act, colloquially called the “Surplus Act”, which made some significant changes to the Pension Funds Act. The changes introduced minimum benefits that a member of a fund could qualify for, it allowed the transfer or withdrawal of funds without “penalty”, and afforded members of the fund a portion of distributed surpluses accumulated by said funds.

In simple terms, the Surplus Act aimed to ensure that former members of pension and provident funds get paid their full share of their fund benefit when leaving a defined benefit fund, and they would be included in a surplus distribution exercise without making the pension or provident fund insolvent.

This is because many pension and provident funds at the time had huge surpluses because not all former members had been paid their full entitlement when they exited the fund.

Before the 1990s, most pension and provident funds in South Africa were Defined Benefit (DB) Funds, and contributions paid into a DB fund were based on a calculation that does not necessarily aim to align the number of contributions with the benefit that will be paid when the member exits, but was aimed at paying out an agreed value at the age of retirement.

Most fund rules applied to vest scales, which meant that a member could not receive their full benefit when they left the fund unless they had worked for the employer and contributed to the fund for a stipulated number of years.

So anybody who resigned from Eskom prior to 2001, and opted to remain rather than withdraw (as the transfer was not possible in terms of the law), remained stuck in this vortex. Those who opted to do the same after 2001, when the transfer was possible, also remain stuck in that rut to the end of their days. It is a once in a lifetime choice, according to the fund rules.

“I tried subsequently, on many occasions to move the money into a preservation fund at another investment house,” says Bruce, “as the EPPF went through many periods of significantly underperforming the market, where I had other investments. I was simply told to ‘relax’, as I was going to become an Eskom pensioner whether I like it or not.”

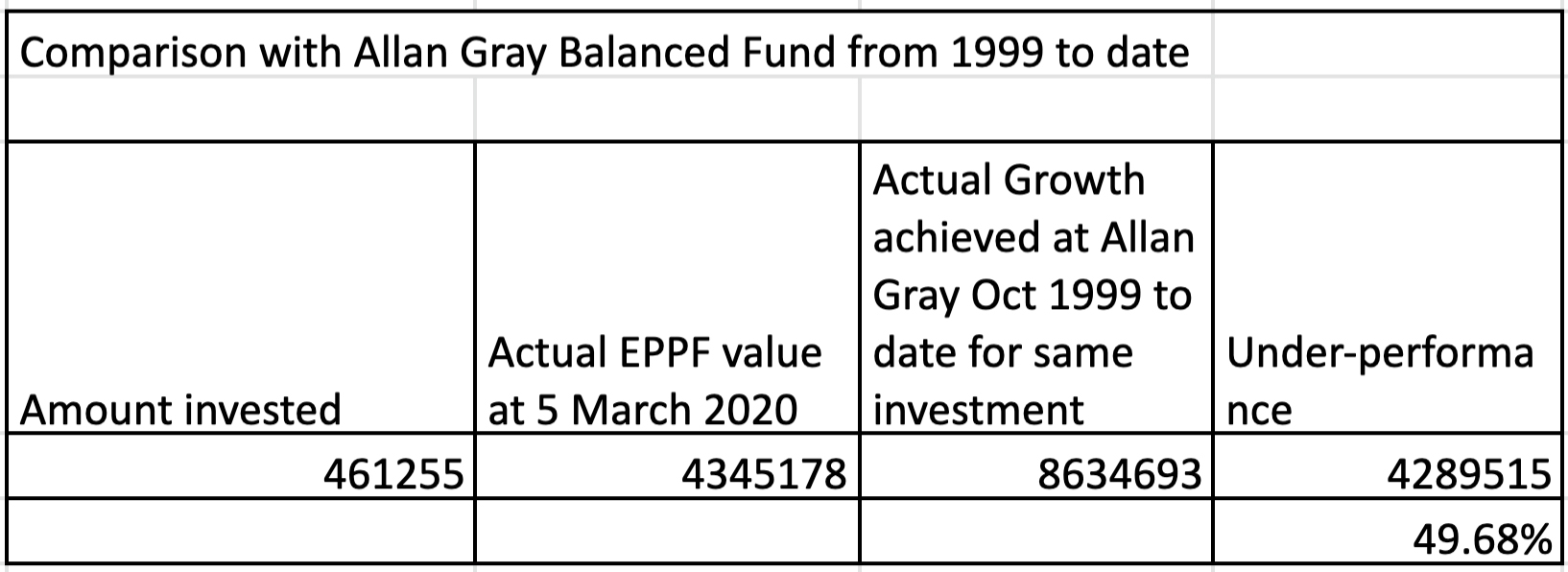

Benchmarked with the Allan Gray Balanced Fund, in which Bruce also holds investments, the restriction of movement does prove a hard blow. Similar to the EPPF, the Allan Gray offering is also a conservative proposition, with a long-term growth focus and is lacking in speculative positions.

Comparing fund performance from 1999 to date, the actual values at the respective fund level in March 2020 shows a 49,68% difference in performance:

“This shows that my R4.3-million investment could have been worth R8.6-million today if I was allowed to move my money elsewhere,” says Bruce.

Bruce blames the incompetence of the fund’s internal investment team and the blatant mismanagement of the fund administration, some of the very matters Business Maverick has been reporting on over the last few months. “Or perhaps it is just the way the funds are allocated to the captive group or a combination of all three,” he adds.

He says he is simply a spectator to the horror show of value destruction, which is the current investment performance and future prospects of his retirement savings housed at the EPPF. The EPPF reported an investment return of 4.5% in the financial year to June 2019.

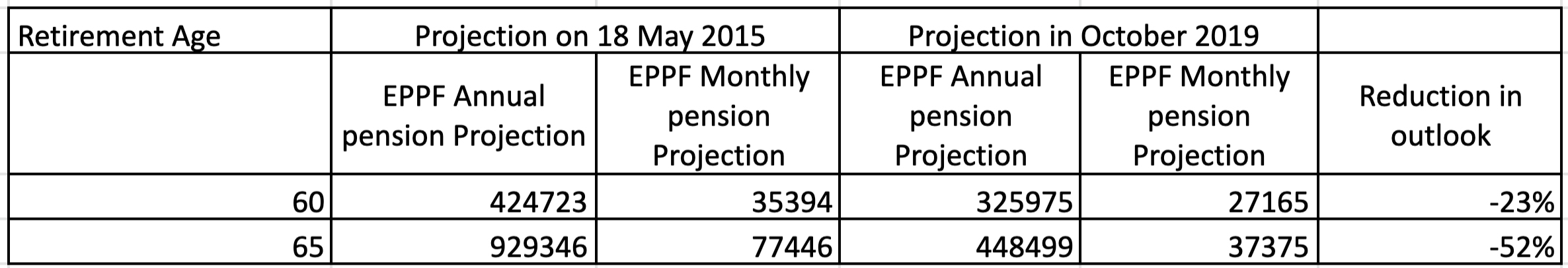

Comparing the projections, Bruce had received from the EPPF, it is clear the destructive behaviour is far from over:

The most recent projection received, Bruce says, was on 5 March 2020, which further reduced his investment projections.

“It has dramatically reduced over time,” says Bruce, “which has impoverished deferred members’ nest eggs significantly”.

“As a result, I have no choice but to continue working way into my golden years and making alternate arrangements for retirement,” he adds. “Other deferred members might not be able to afford this ‘luxury’”, he said.

Adding insult to injury is that, despite the EPPF being a defined benefit fund, deferred members are treated as defined contributors, so all investment losses are carried by the member and not underwritten by the pension fund or the employer itself. And in addition, unlike a living annuity, where the investor has a say on the withdrawal rates, the 2,000 odd members of the “lost generation” just have to be happy with the rates they get, or suck it up and stick it out – which has proved detrimental to their nest egg as the above calculations show.

Industry experts told Business Maverick the state of affairs is not unusual and may even be required for compliance with the conditions for approval as a “pension fund” as defined in the Income Tax Act. But it is inconsistent with the regulations National Treasury introduced many years ago to give members of retirement annuity funds the right to move their retirement savings to other similar structures.

In an email, the EPPF confirmed that the deferred member scheme is governed by the EPPF Fund Rules. “This scheme is a vehicle which enables Eskom employees who leave the employer to protect their pension savings until they attain the pensionable age of 55 when they are eligible to go on retirement,” they say.

“The conditions of the scheme for deferred members have always stipulated that the decision to defer a transfer value is irrevocable once made. This rule has not changed since inception and is unlikely to change as the EPPF seeks to encourage the preservation of retirement benefits.”

“Prior to 2001, the fund rules permitted deferred members to continue contributing towards the scheme after they had deferred their benefit. In 2001, the Fund was guided by the South African Revenue Services (SARS) to amend its rules to discontinue the additional contributions by members after they defer their benefit due to the dissolution of the employer/employee relationship. This is the only rule change that has been made affecting the deferred member scheme,” it adds.

A retirement risk consultant tells Business Maverick that what trustees should do is ask themselves whether these selective and restrictive fund rules are fair to the members in question. “For one, the law won’t allow you to do so today and furthermore, the situation is in conflict with their fiduciary duty of acting in the best interest of its members in terms of Section 7C of the PFA.

“It is not as much about sub-optimal asset management performance,” he says. “One can lose money anywhere. It is about allowing member choice and the freedom of association.”

Whether deferred members qualify for the EPPF’s surplus distributions, which by law they should, remains unclear, as the EPPF did not touch on this point in their email and Bruce says he has been struggling to get confirmation or any proof of the case from the EPPF. BM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider