BOOK EXTRACT

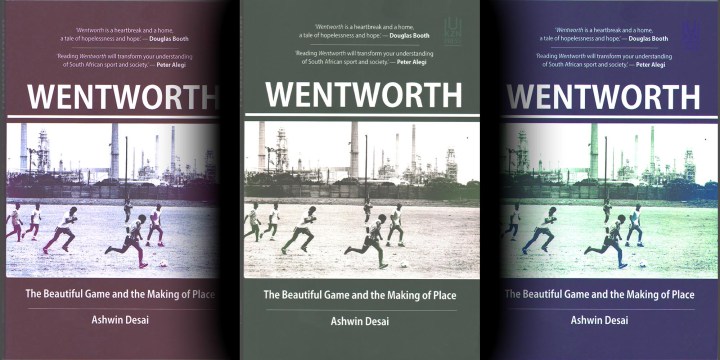

Wentworth: The Beautiful Game and the Making of Place

This book is about pioneering attempts to build the beautiful game in Wentworth. It is intertwined with housing battles, gangs, sexuality and the looming presence of the petrochemical companies that provide jobs and make the area the most polluted in Durban. This is a tale that broadens into a cast of other players, supporters and teams. In the process, they also speak of Wentworth, a place they sought to make as their world, as much as they were made by it.

In South Africa of the 1960s, at the exact time that so many neighbourhoods were being destroyed under mass relocation programmes, the quest for identity had to find surrogates. Soccer. Clubs were formed. Patches of turf were secured as a bleak landscape was turned into expressions of skill and desire to win trophies as well as developing the talents of a new generation. All this took sacrifice, a sense of mission, and for some at least, a commitment to the long haul of turning Wentworth, an apartheid-imposed Coloured township, into a place, a home. Perhaps that is also why the friendships borne in hardship and want are the most powerful.

Dolores Hayden (1995) warns that “place is one of the trickiest words in the English language, a suitcase so overfilled one can never shut the lid”. Once I opened the lid on the history of soccer in Wentworth, I could not stop looking. Photographs, trophies, beautiful memories, deep wounds that refuse to heal. Every time I tried to shut this suitcase, it burst open with the force of a suppressed memory suddenly recalled on the psychologist’s couch. It is what makes oral history exciting and challenging as one deals with deep emotions as much as fading and selective memories…

Gary Goldstone. One of Wentworth’s most iconic players. To write a life is to have a sense of a timeline that is linear. But when you listen to teammates describe Gary on the field, you realise there were no straight lines. He was all body, spontaneous and fluid, dominating the midfield, always on the edge of fury. But why then is he talked about with such tenderness? In all this, you see, there was a vulnerability, hovering on the precipice of self-destruction, a sadness even.

Goldstone embodied the spirit of the times. Wentworth. The 1970s.

Soccer players trained in grounds next to petrochemical firms that spewed black smoke into the air 24 hours, 365 days of the year. Schoolchildren packed asthma pumps alongside their lunch boxes. Cancer rates rose. Coffins of the young were lowered. Men left home to seek work in the Highveld. No matter how long you worked at the local chemical plants, you were always temporary, always on contract. The horizons for a top soccer player were limited to a pittance as a part-time professional. Gangs and drugs, like Jehovah’s Witnesses, always came knocking. To keep going at the top of your game, to pull others along with you, to remain competitive, to be a leader as Goldstone was, permanently poised, with a mad love of the round ball and a desire to win, meant a heavy dose of craziness, irrationality even. When you talk to those who shared a change room, who watched him play, it is these qualities that make Gary Goldstone so revered. Then. And now. But there is also something else. A shock, a suspicion even that Goldstone survived. When many fell. Like his dominance of the midfield, he pulled it back together and made a life.

As an aside, I ask a lifelong friend what makes Gary Goldstone a figure that endures through the generations… his reply intrigued me; “Gary lived against lies that we were nothing, because despite everything that was thrown at us, he felt we always had to prevail on and off the field; he was unstoppable but vulnerable. He still is.”

I was reminded of the words of Jacques Derrida who wrote of the person who lived as “the friend of truth – but a mad truth, the mad friend of truth”.

And it was a round ball that held the line between Goldstone’s genius and madness; between falling into an abyss or shallow grave and today tending his garden with the air of a man who refused to die, born-again.

How to capture a life? Gary Goldstone. Sometimes spoken about loudly, sometimes in hushed tones, Goldstone’s soccer was not just about his immense ball-playing skills. It was about the way he conducted himself on and off the pitch. On the field he wanted to win, throwing incredible energy into motivating his own side to greater heights, even to the extent of slapping his own centre-forward for missing a goal. In the change room, he would show his anger if Leeds lost, sometimes even demanding his goals back. And off the field, he lived life his way; he got into trouble with the law, entered a mental home and partied hard. In Argentinian football, there is the image of the pibe, born in the ghetto, who starts life playing on patches of land, with Diego Maradona as the most obvious example:

The image of the typical pibe player is based on exuberance of skill, cunning, individual creativity, artistic feeling and improvisation … a lot of disorder is expected … There is a tendency to disregard boundaries, to play games even in private life (life is experienced as a permanent game or gamble if necessary); additionally there is a capacity of recompense, penalise or forgive others in an exaggerated way; to convey arbitrary judgements and choices; to display irrational and stupid heroism, and a capacity of ‘die’ (by being imprisoned, a drug addict or alcoholic) and to be resurrected; and a special talent in critical games to make the unexpected move, ensuring victory for the team . . . The pibes serve as mirrors and, at the same time, operate as models defining the ideal of a style, a way of playing (Archetti).

As those who played alongside and against Goldstone attest, his way of playing, of living, of the sheer will to win changed Leeds and those around him. As was said of the pibe Maradona, “the teams that Diego played for were transformed by his aroma” (Archetti 1997). And that is what Goldstone gave to Leeds in its heyday, changing it into a team that played with style but also a winning mentality. Goldstone epitomises Goldblatt’s epigraph that began the journey of this book; “It is for winning, and winning in style … Because, when it came to it on the pitch, when the whistle blew and money, power, status, reputation and history were all sent to the bench, you wanted it more”. DM

The author is Professor of Sociology at the University of Johannesburg. The book was published by UKZN Press.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider