OP-ED

Why poaching has decreased dramatically in Mozambique’s Niassa Reserve

Mozambique’s far northern Niassa National Reserve, one of the great wilderness areas of Africa, was also until recently an elephant killing field where poachers operated with virtual impunity. Now, the poaching has been dramatically curbed and the ivory trade disrupted. The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime reports.

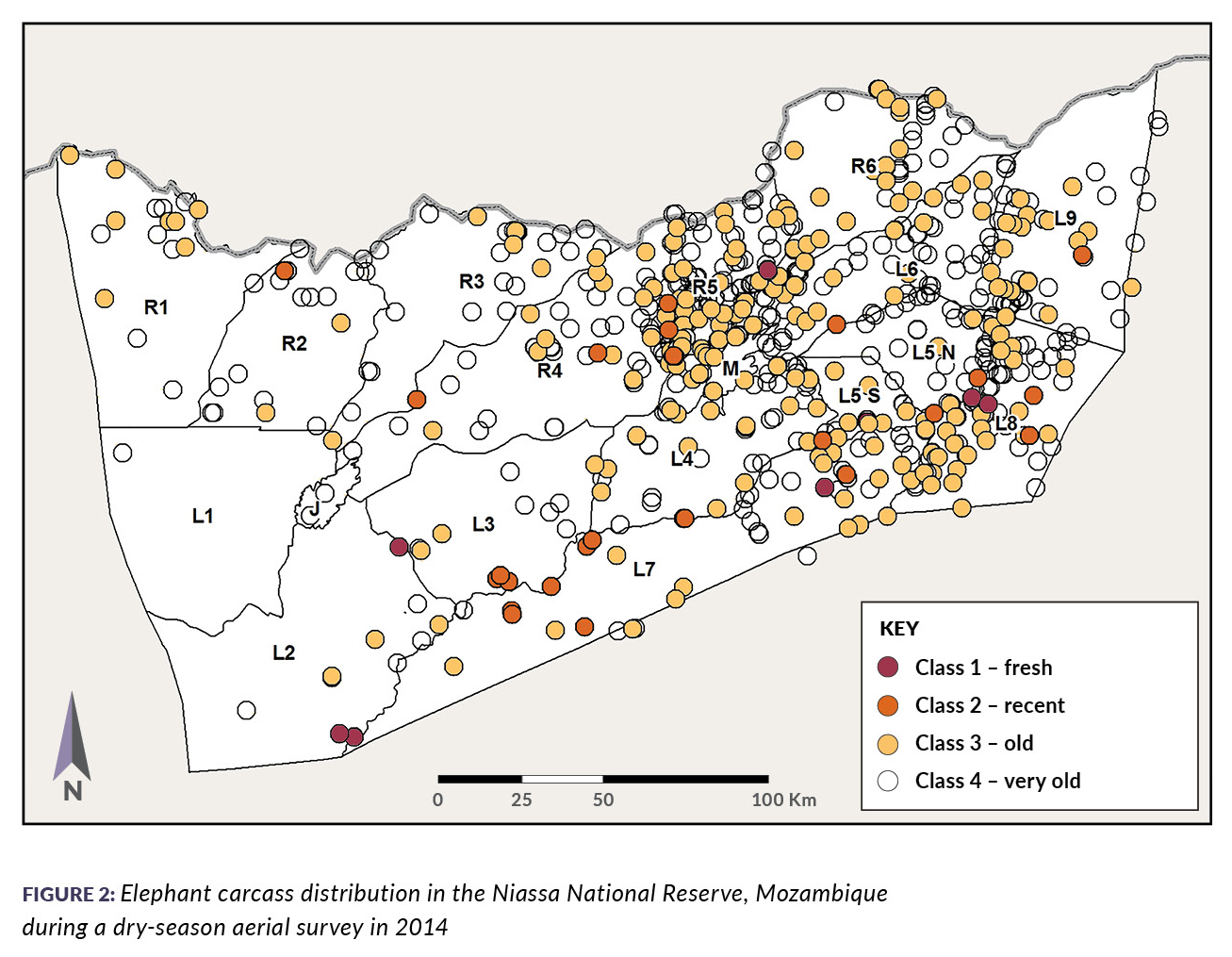

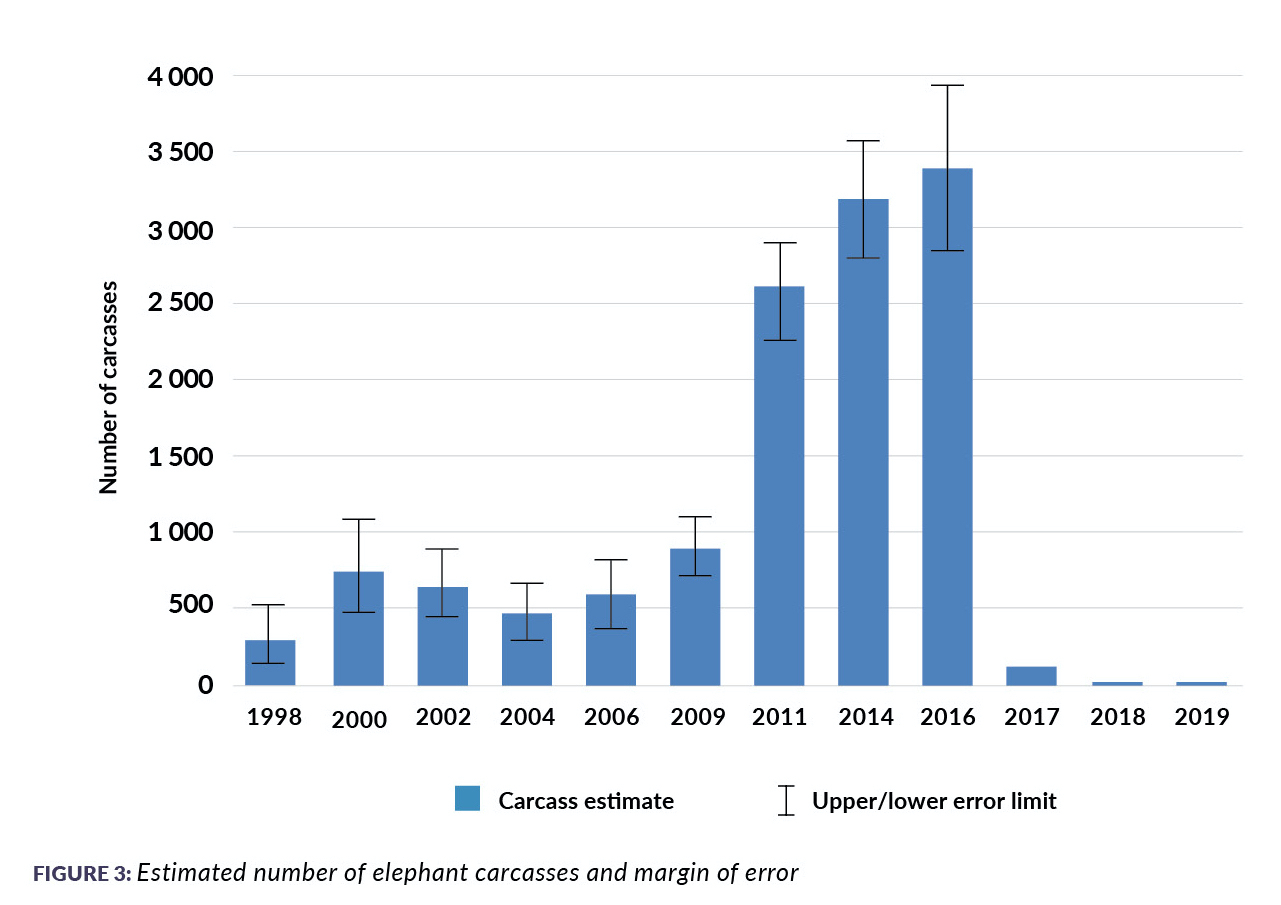

From 2009 to 2014, Mozambique lost nearly half its elephants to poaching: the elephant population declined from an estimated 20,000 to 10,300. The majority of this loss occurred in the Niassa National Reserve in northern Mozambique, where the population fell from an estimated 12,000 in 2011 to about 4,440 animals in 2014.

Despite the significantly lower density of elephants in Niassa, the poaching continued into 2017 and early 2018. However, in May 2019, Mozambique’s National Administration of Conservation Areas (ANAC) announced that it had been a year since a poached elephant had last been found in the reserve. Later in 2019, ANAC released the results of the 2018 national elephant census, revealing a stabilisation of the national population, with an estimated 9,122 animals, although losses are still occurring in key populations in the west and south-west.

Niassa Reserve, at 42,300km², slightly larger than Switzerland, is one of Africa’s few remaining remote wilderness areas where large elephant, lion and wild dog populations still roam. This started changing in 2009 when the rampant elephant poaching underway in Tanzania shifted south across the Rovuma River into the northern part of the Niassa Reserve and affected the whole reserve by 2013–2014.

By 2014, the poaching had also become increasingly professionalised, carried out by specialised gangs using high-calibre hunting rifles.

By late 2014, northern Mozambique, and the port of Pemba in particular, had become a significant hub for ivory trafficking. Ivory was trafficked from Uganda, and possibly further west, overland and by dhow down the coast from Tanzania to northern Mozambique and then to Asia.

By 2016, ivory stockpiles in Mozambique were being raided, and poaching of the Niassa Reserve elephants continued, even though the low density of elephants made them hard to find. Before 2014, most ivory from elephants poached in northern Mozambique was moved into Tanzania and exited the African continent from East Africa; but with the shift of trafficking to Pemba and Nacala in northern Mozambique, ivory stolen from stockpiles and poached in the Niassa Reserve began moving directly from Mozambique.

The first actions that contributed to the later reduction in poaching started in 2017 and 2018.

A key event was the July 2017 arrest and repatriation to Tanzania of a major ivory trafficker who had been operating in northern Mozambique with impunity since 2013. The arrest and transfer were the result of a three-year investigation involving a multi-agency collaboration between ANAC, the National Criminal Investigation Service of the Police, and the Attorney General’s Office, with NGO and donor support.

In 2014, this trafficker had been operating five poaching gangs in the Niassa Reserve. Just two of the gangs had together supplied him with 825kg that year alone. There is also evidence tying him to the theft of 867 pieces of ivory from a stockpile in northern Mozambique in late 2016. He was well known for maintaining a local network of bribery payments to maintain his anonymity and security – making his arrest and repatriation even more notable.

Following this arrest, and based on information gained from interrogations, a further six ivory traffickers operating on the eastern side of the Niassa Reserve were arrested and convicted in court in the province of Cabo Delgado in northern Mozambique. At the same time, higher-level networks trafficking ivory from the ports of northern Mozambique were being exposed, and in some cases dismantled and individuals arrested.

Recent fieldwork in Pemba, Mozambique, by a Global Initiative team found no indication of ivory being trafficked through that port. Other sources in the area have indicated that the local ivory trade has ceased because the perceived threat of arrest and conviction is high. The same sources suggested that local ivory traders are holding small stockpiles from the past, but are too afraid to move or sell them.

In early 2018, changes were also made on the ground in the Niassa Reserve. Key partners – ANAC, the police, the Wildlife Conservation Society (ANAC’s co-management partner for the reserve), the Niassa Conservation Alliance and other operators – began to implement a coordinated anti-poaching strategy. This included deploying a specialised rapid-response police unit, appointing a senior police liaison officer to coordinate all police forces with reserve scouts, better equipping the scouts, making a light aircraft available year-round, and chartering a helicopter during the 2018 and 2019 wet seasons.

Improvements in communications were also made through investment in a radio network and regular meetings between the partners. In addition, the partnership cleared out illegal mining and fishing camps in the reserve. Finally, a significant proportion of the elephant population was collared and tracked in order to focus protection activities. In the first 12 months that the police rapid-response unit operated in the reserve, they arrested 46 people, of whom 26 were convicted.

A final key component of the reduction in elephant poaching in Niassa Reserve has been high-level political support. In November 2018, Mozambique’s president, Filipe Nyusi, visited the reserve and participated in a widely publicised elephant-collaring operation. He used this opportunity to emphasise the need to restore the rule of law, while also reducing resource conflicts with local people.

It is unlikely that the decline in elephant poaching in the Niassa Reserve is purely the result of effective anti-poaching operations and increased sentencing. Our recent fieldwork ascertained that while ivory from the Niassa Reserve was not for sale, live pangolins are, and local sources confirm that pangolin scales and lion bones originating from the reserve still transit Pemba and can be sourced if wanted.

It is not surprising that anti-poaching operations alone in an area the size of the Niassa Reserve have not stopped illegal wildlife trade across the board. Further, there is evidence that sentence length alone is not a good deterrent, but rather the likelihood of being caught and a sanction occurring have a higher impact on deterrence. This may be exacerbated in Mozambique where prison overcrowding means that prisoners are fairly regularly released early to make space for new offenders.

Therefore, while effective anti-poaching operations and effective sentencing are key components of improving the rule of law in and around protected areas, there may be several other key factors that are critical to reducing organised high-value poaching. In this instance, key specific factors include:

- The 2017 arrest of northern Mozambique’s most notorious ivory trafficker, who was the key link between poaching and stockpile thefts in northern Mozambique and the Pemba ivory traffickers;

- The immediate follow-on arrests of lower-level ivory traffickers;

- Disruption of the corrupt protection of ivory traffickers and poachers, which has, in turn, broken the general perception of impunity;

- The increased perception of the likelihood of arrest and conviction for ivory trafficking resulting from the recent crackdown;

- Reduced demand for ivory from traffickers in Pemba, which had become a major centre for transnational ivory trafficking;

- Cooperation between trusted individuals in key government law enforcement agencies (ANAC, the National Criminal Investigation Service and the Attorney General’s Office), to overcome information leakage from local law-enforcement agencies;

Direct operational support from donors and NGO partners for these cooperating law-enforcement activities;

- The work of international law-enforcement agencies to dismantle the ivory-trafficking networks operating from northern Mozambique; and

- High-level political support.

At the same time, the wider context of the breakdown of the rule of law in northern Mozambique due to ongoing violence, and other ongoing illicit trades in the region, must be borne in mind. The specific successes described here should be attributed to improved rule of law that focused on a specific product – ivory. This has overcome a culture of impunity and created a feeling of vulnerability in the criminal networks dealing with that product. DM

This article appears in the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime’s monthly Eastern and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin. The Global Initiative is a network of more than 500 experts on organised crime drawn from law enforcement, academia, conservation, technology, media, the private sector and development agencies. It publishes research and analysis on emerging criminal threats and works to develop innovative strategies to counter organised crime globally.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider