US2020: DEMOCRATIC BATTLEGROUND

Nevada, Soweto, Russia… US politics meanders into even stranger waters

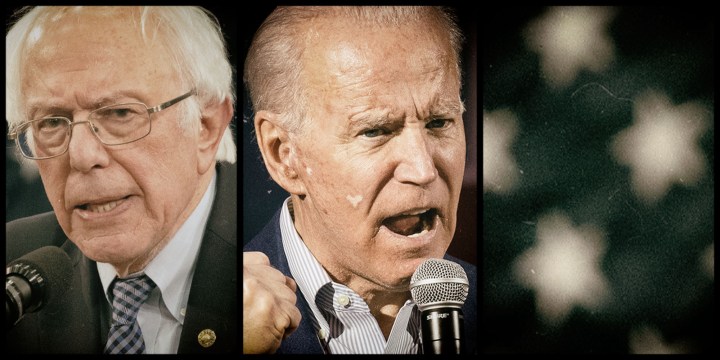

The third state battle for the Democratic nomination is now over and Bernie Sanders has clearly edged into the frontrunner spot, enjoying quite a momentum. But there is so much more left to happen. Somehow both Russia and Soweto found their way into this contest as well.

The US electoral process in the 2020 election, largely a Democratic Party affair for now, continues to lumber forward as numerous missiles were fired at the candidates – by those same candidates at themselves. But there have been even more disconcerting moments.

Over the past weekend, on 22 February, the state of Nevada had the country’s second caucus, this one somewhat less chaotic than the first one in Iowa. There, reporting the final results was delayed by days of public bungling, ineptitude, and administrative muddle by the state’s Democratic Party.

In the just-completed Nevada caucus, by Sunday the near-complete results showed Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders would now be able to claim bragging rights to the largest number of pledged delegates for the mid-July Democratic presidential nominating convention. However, the vast majority of delegates remained to be determined, with only 96 of the nearly 3,000 delegates pledged to the various candidates so far.

To become the Democratic Party’s nominee, a candidate needs to win a majority of the party’s delegates. Up until the Nevada caucus, five candidates had earned delegates from the first two contests: former South Bend, Indiana, mayor Pete Buttigieg (23), Sen Bernie Sanders (21), Sen Elizabeth Warren (8), Sen Amy Klobuchar (7) and former vice-president Joe Biden (6).

Following Nevada, results for the leading candidates came through in this order, with about half-plus of the votes tabulated: Sanders 46.6%; Biden 19.2%; Buttigieg 15.4%; Warren 10.3%; and Klobuchar 4.5%. The state’s county delegate convention is therefore likely to allocate 15+ delegates of its 36 national delegate total to Sanders, and maybe nine or 10 to Buttigieg, depending on how the actual vote distribution broke down precinct by precinct, across the state. That would give Sanders 36 total delegates or so at this point, and with the second-place candidate, Pete Buttigieg holding perhaps 34.

Polling says the most important factor for many Democratic voters in picking a candidate has been his or her perceived ability to defeat Donald Trump. Importantly, the data seems to point to a view that Sanders embodies that quality. Moreover, significant chunks of the voting electorate appear to have accepted Sanders’ arguments over a national health plan. Additionally, Sanders did particularly well with younger and Latino voters. For Sanders supporters, therefore, these are real grounds for their optimism for the weeks ahead.

But it is crucial to remember a candidate needs half plus one of a total of 3,979 delegates, and the vast majority have yet to be selected. However, 54 delegates are up for grabs in South Carolina this coming weekend, 1,357 are at stake on 3 March, 352 on 10 March, and 557 more a week later.

Despite all the victory chants from supporters that Sanders is already a done deal, the reality is that the proverbial fat lady hasn’t even gone on stage, let alone sung her song. But, by the end of March, she almost certainly will be on the last few pages of her final aria, unless a three- or even a four-way race has so divided up the pledged delegates that while there is a leader, no one candidate has a lock on a majority. Then the dreaded words “brokered convention” will be talked about – a lot.

In this entire process, as noted above, the Democrats divide their 3,979 pledged delegates among the states, the District of Columbia (the city of Washington), some miscellaneous territories and a couple of other jurisdictions without electoral votes. This distribution is based on a formula that takes into account both population and the Democratic Party’s strength in particular jurisdictions. Thus, while Massachusetts and Tennessee have similar populations and 11 votes each in the electoral college, more people vote for Democrats in the former than the latter. As a result, Massachusetts gets 91 pledged delegates, while Tennessee garners just 64.

Those delegates are then pledged to candidates from the results in the primaries and caucuses, subject to a number of lawyerly footnotes. For Democrats, a quarter of each state’s delegates are awarded on the basis of the statewide vote, and three-quarters are usually awarded on the basis of results by congressional district. Sometimes, particularly in states with just one congressional district, the delegates are awarded on the basis of the results from a smaller jurisdiction, such as state legislative district.

Moreover, a candidate must hit 15% support of the total vote in order to win delegates, either statewide or in a congressional district or smaller district. That may be difficult to achieve in a field as large as this year’s Democratic class. For example, if one candidate gets 40% support statewide, another gets 15% support, two others get 14% and others get less, only the first two will split the statewide delegates, proportionately.

There are also “superdelegates” – party officials and leaders and establishment figures. But, importantly, under new rules adopted after the 2016 primaries, superdelegates will not participate in the first vote at the Democrats’ nominating convention unless one candidate has already achieved a majority of the pledged delegates.

But, if the nomination isn’t settled by the beginning of the convention, those superdelegates’ votes would then factor into the selection of a nominee. But this would only be a factor from a second ballot onward.

As if the suspense of the actual, ongoing primary votes was insufficient, several other occurrences have been vying for our attention as well. First was the effective unveiling of Michael Bloomberg’s heretofore entirely electronic, virtual campaign as a candidate for the nomination. This was actually taking place even before his name had appeared on any ballots and thus before he had received a single vote.

To say the least, this political coming-out party for Bloomberg was not an unvarnished success. Participating in his first Democratic candidates’ debate, Bloomberg appeared, by turns, irritated, petulant, rattled, and largely unprepared for the barbs tossed at him by the other five competing candidates.

What he did not appear to be was the well-prepared master of the universe that would have befitted his having been a three-term mayor of New York City, serving in what is often called “the second most difficult job in America”. These circumstances, taken together, almost made it seem as if there are two Bloombergs on show: on the one hand, there was the towering force of nature on view in his gargantuan media buy’s worth of television and online messages.

But, on the other hand, there was the more diminished, almost oratorically diminutive figure who had appeared in the six-candidate debate. There will be yet another debate on Tuesday in South Carolina, and all eyes will be on whether Bloomberg can do a reset; if Sanders can consolidate a frontrunner status; and whether Biden, as well as Buttigieg, Warren, and Klobuchar, can claw their respective campaigns right back into the centre ring of contention.

In just the past few days, without getting much space to demonstrate his knowledge, experience, business and governmental acumen, and broad acquaintanceship with national and international economic issues, Bloomberg has been chivvied by the other candidates (and the media) for his humongous spending on his commercials (aka the charge of “buying the nomination”); an alleged record of near-Trumpian bad-boy language and behaviour towards women in his companies; and the hard racial realities of the stop-and-frisk police practices in New York City, carried out during his tenure as mayor.

Meanwhile, Biden did well enough to stay in the hunt, barely; while Buttigieg continues to hang in there too, although his ability to close the deal with minorities remains in serious question. Senators Amy Klobuchar and Elizabeth Warren had relatively disappointing outcomes, but not enough to drive either out of going forward. South Carolina seems to be a landscape where candidates will either prove their worth with that state’s black voters or begin their final fade.

In all this horserace politics and reporting and the growing level of personal attacks, the issues dividing and uniting the Democratic candidates have been getting less and less attention. Speaking about that concern, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof wrote over this past weekend, “I’ve written a couple of scathing columns about China’s initial mishandling of the coronavirus outbreak, but that feels a bit unfair. Our own health care system is a complete mess; as Walter Cronkite once said, it’s neither healthy, nor caring nor a system. So if we’re going to hold China accountable we should do the same for ourselves – and that’s the purpose of today’s column.

“An election year should be the perfect time to do that. But Democrats are bickering over Medicare for All, which Congress will never adopt anyway. Instead, the focus should simply be on ensuring universal coverage whether through a single-payer system like Britain’s or a multi-payer system like Germany’s (both work well). Meanwhile, Trump is working to dismantle Obamacare, and 400,000 children have lost health insurance. That hasn’t gotten nearly enough attention. Think about that: parents who can’t take a son to a doctor if he’s not learning to speak, or a daughter if she’s not growing properly or has an ear infection.”

The horserace seems more important than the why of an election, sadly.

Meanwhile, while all this was taking place, the government’s national intelligence community had given a closed-door briefing to the House Special Select Committee on Intelligence on foreign intervention attempts and plans to – yet again – interfere in the US national election. The briefer’s conclusions were that the Russians were going to be helpful to Trump’s chances in the general election yet again, and that they were similarly gearing up to help Sanders in his primary battles. For his part, Sanders responsibly denounced any such actions, and he called Vladimir Putin a thug for good measure, as well.

By contrast, Donald Trump called the whole thing “hoax #7”, and summarily ran the acting director of national intelligence right out of his job for allowing a staffer to have the temerity to provide Congress with these intelligence community’s findings. Then, Trump’s newest national security adviser publicly dumped on candidate Sanders, even as the adviser said he had seen none of the conclusions or evidence the briefer had just discussed with Congress. If one is looking for a motive, a pretty good set of them would be these three: to sow yet further chaos in the Democratic Party; to support a president who loves the Russian leader and keeps drawing back from places of interest to the expansion of Russian influence; and to enhance further distrust by Americans (and foreigners) in the country’s political life.

But surely the weirdest part of the week came with a special connection for South Africa. Seemingly out of the blue, Biden announced he had been arrested in South Africa during a 1977 visit, presumably while he was in Soweto and hoping to visit Nelson Mandela on Robben Island. Yup, arrested. Now the thing is, nobody else seems to have remembered this arrest. It is not mentioned in Biden’s previous writing on his life (or about this visit), and there appear to be absolutely no media reports of such an arrest, either in South Africa or the US.

Speaking as someone who had worked on numerous congressional visits (representatives and senators both) in several countries, including South African over three decades, virtually every one of those visits had an embassy staffer acting as the visitor’s schedule control officer. In a place as complex, troubled, and volatile as South Africa was in the late 1970s, the control officer and other embassy staffers (right up to the ambassador) would have given microscopic attention to the schedule and its logistics to ensure the congressional visitor’s interests were taken into consideration, but that nothing should go off the rails.

If the local police had arrested or even tried to arrest a US senator, there would have been absolute hell to pay. For everyone. Such visitors often went to Soweto to meet controversial people or visit local sites (including our own newly-established US embassy library there), but such visits were, like everything else, just as obviously, monitored by the local police or other security forces.

And as for Robben Island, then as now, there are just two ways to get there, either by boat or by helicopter and both were – and remain – under the control of the South African government. There would have been no specially arranged privately chartered travel there for a visitor. Moreover, back in the 1970s, Mandela was only receiving obvious family visits or rare visits from his legal representatives.

Now as to the “why” of this sudden pronouncement from Biden, we can only speculate. Perhaps it was one of those mature (ie older) politician’s moments where intention gets confused with the act. Ronald Reagan, for example, became well-known for speaking about important events in World War II as if he had been there, rather than his having acted out those carefully on a Hollywood backlot for the silver screen.

Perhaps, less charitably, Biden was somehow attempting to appeal in this way to South Carolina’s black voters for their upcoming primary, by identifying so closely with the famous icon. Or perhaps it had just seemed like too good a thing not to misremember.

While most American voters will likely forget about this, or never even hear about it, it may become yet one more of those things that call into question Biden’s acuity, focus, and mental agility at this stage of his life, just when his momentum is sputtering or stalled completely.

Watching all these dramas, I realised there is a play to be drawn from all this, somewhat like a mix of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and Edward Albee’s Zoo Story. Our play would take place on a city park bench where Bernie Sanders and Michael Bloomberg are feeding the pigeons while they debate the country’s economic state and its future.

Donald Trump then comes over and tries to join the conversation, but his interjections are largely stream-of-consciousness rants about Hillary Clinton and his other favourite bêtes noires. Meanwhile, Joe Biden leans over the back of the bench similarly attempting to join the increasingly vigorous debate between the two men on the bench. Poking out from among the trees are the rest of the candidates. They wave their arms, but they barely get a word into the conversation.

Eventually, the bench conversation gets so heated, Sanders and Bloomberg throttle each other into unconsciousness. Trump sits down on the bench by himself, but Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Kim Jong-un, and a masked ayatollah all come on stage and crowd Trump right off the bench and then the stage. Whatever I ate last night, I must never have that again! DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider