Human Rights

South Africa could play important role in South Sudan – UN

South Africa could advise South Sudan about its transition from conflict to peaceful government, despite its own imperfections, say United Nations human rights commissioners.

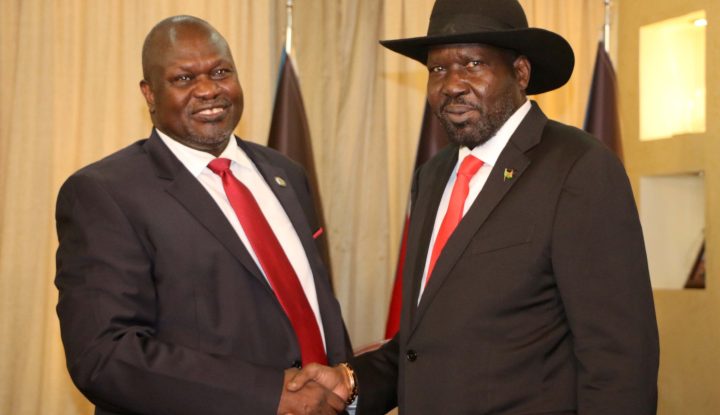

The release of a United Nations Human Rights Council report on abuses in South Sudan on Thursday 20 February coincided with an agreement between the warring leaders, President Salva Kiir and former rebel leader Riek Machar, to form a unity government on Saturday 22 February. Two such agreements since 2011 have already ended in disaster. The Report of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan details a host of abuses in the country since renewed conflict broke out in the continent’s youngest country in December 2013.

It found that millions of civilians had been deliberately deprived of access to basic services, and many were starved while the country’s politicians siphoned off national revenues, much of it from petroleum. Corruption and political competition fuelled human rights abuses and are major drivers of ethnic conflict in the country, which saw twice as many deaths in 2019 than in 2018, according to the commission. Children as young as 12 were recruited to fight by both sides. More than 55% of civilians countrywide, mainly women and children, face food insecurity, the report found, and this is exacerbated by climate-induced factors such as the locust plague that has beset the region.

Commission member Barney Afako, who joined commission chair Yasmin Sooka for a press conference on the report’s release in Johannesburg, said the role of South Africa in South Sudan’s transition was “terribly important” and should go beyond public statements to actual engagement.

South Africa is the chair of the African Union, which played an important role in the South Sudanese peace process, and it has a seat on the United Nations Security Council as a non-permanent member in 2020. It is also one of five African countries involved in the peace talks, with Deputy President David Mabuza currently tasked with the responsibility of representing South Africa in the process. President Cyril Ramaphosa has singled out the conflicts in South Sudan and Libya as the AU’s top priorities for 2020.

“It is terribly important for a respected African country to intervene, not just publicly, but also in a close way, providing support to South Sudanese leaders, [and] advice on how to govern and how to manage resources,” Afako said, adding that this included managing corruption. South Sudan could also learn from South Africa in the way leaders have addressed issues of accountability and reconciliation.

There is irony to these recommendations, though, because South Africa is still very much grappling with most of these issues within. Add to this list of ironies the ANC’s own battle with growing divisions while having to advise the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement on ways to achieve unity. The truth and reconciliation process South Africa embarked on following the first democratic elections in 1994, has been similarly imperfect. SABC foreign editor Sophie Mokoena asked Sooka how South Africa could be an example to South Sudan if its own process is flawed of holding leaders to account for crimes committed under apartheid, including former president FW de Klerk. Sooka herself served on South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In a long answer to this question, Sooka described South Africa’s process as a complex one with compromises. “When South Africa had its own transition it was incredibly influenced by the process in Latin America,” she said. The transition to democracy there was from military dictatorships and authoritarian rule, whereas South Africa was emerging more from a scenario where there was conflict in which citizens were targeted. “Also, you had a racialised system of laws under the system of apartheid which was declared a crime against humanity by the [UN] General Assembly,” she said.

Some balance was also necessary to avoid instability. The first democratic president after the military dictatorship in Argentina, Raúl Alfonsín, who came to power in 1983, almost lost power when he tried to persecute the military heads and middle level officers, and he was compelled to pass a law that gave them amnesty, Sooka said.

“The real question that held up the signing of our Interim Constitution [in South Africa] was this question of criminal accountability,” she said, with some calling for a general amnesty and human rights lawyers arguing for accountability, but not at the cost of destabilising the new government.

In the end there was a conditional amnesty premised on full disclosure, she said. “You had to prove that the actions of the crimes you had been implicated in were committed at the instance of the former state and its different organs or of the liberation movements.” She said that, by law, if you didn’t apply for amnesty or were refused, the law should take its course, and this has been the battle that many victims and their families had pursued between 2003 and 2016 to ensure proper accountability.

Sooka said the AU’s view was that it’s not an either/or choice.

“Criminal accountability on its own is not sufficient,” she said, because when you prosecute those with the greatest responsibility there are “impunity gaps”, dealt with by mechanisms like a truth and reconciliation commission. Other domestic processes as well as reparations were also part of accountability.

The hybrid court which should be set up in South Sudan according to the 2015 and 2018 peace deals was “not a figment of the imagination or a creation of the West,” she said. The AU’s commission led by former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo recommended a hybrid court on the basis of the crimes that had taken place, as well as a truth commission and a reparations authority. The hybrid court will incorporate prosecutors and judges from South Sudan as well as the rest of Africa, and consider aspects of domestic and international law.

The UN believes there should be more urgency to getting the court up and running, and the South Sudanese government should be bypassed if necessary. The repeated outbreak of conflict in South Sudan had become a way of shifting out the formation of the hybrid court, Sooka said.

“In our report we want a legal interpretation of the resolution of the AU saying: ‘you have the authority to set up this court’.” She said it was also a test of the AU’s own credibility and commitment in dealing with serious international crimes on this continent. She said the commission had compiled a list of more than 100 names of those who should be prosecuted when a hybrid court was up and functioning. It also kept open the possibility of involving the International Criminal Court.

Afako said the commission wanted the AU to put forward a timeline by which the South Sudanese should have co-operated with the establishment of the court. “We expect the delay is now a thing of the past as soon as the new government is formed,” he said. The hope in the continent is that South Sudan’s peace would hold the third time around. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider