MAVERICK CITIZEN: ASTRONOMY FOR ALL

Exploring the words to discover a universe of other worlds

The number of words in all the world’s languages to describe the starry skies we all admire, ponder and fear must be too many to count. Yet, in South Africa, English and Afrikaans continue to dominate the way we speak of astronomy. Two University of the Western Cape masters students have set out to change this, translating resources for high school students into indigenous languages. They hope to connect the dots between the science and the indigenous knowledge of astronomy.

When Chaka Mofokeng finished high school in the Free State, he applied to study astronomy out of curiosity, to stray from the path of engineering so many of his peers were following. It was a leap of faith into a field he had encountered infrequently and, frankly, knew very little about.

He was hooked after his first class, and years later he is about to embark on his doctorate in astronomy at the University of the Western Cape.

He was lucky. Others, not always so much.

He doesn’t want scholars to be at the mercy of luck like he was. He wants astronomy to invite them in, with a greeting in their mother tongue, and assure them that it’s not the stuff of science-fiction – there is a space for them, too.

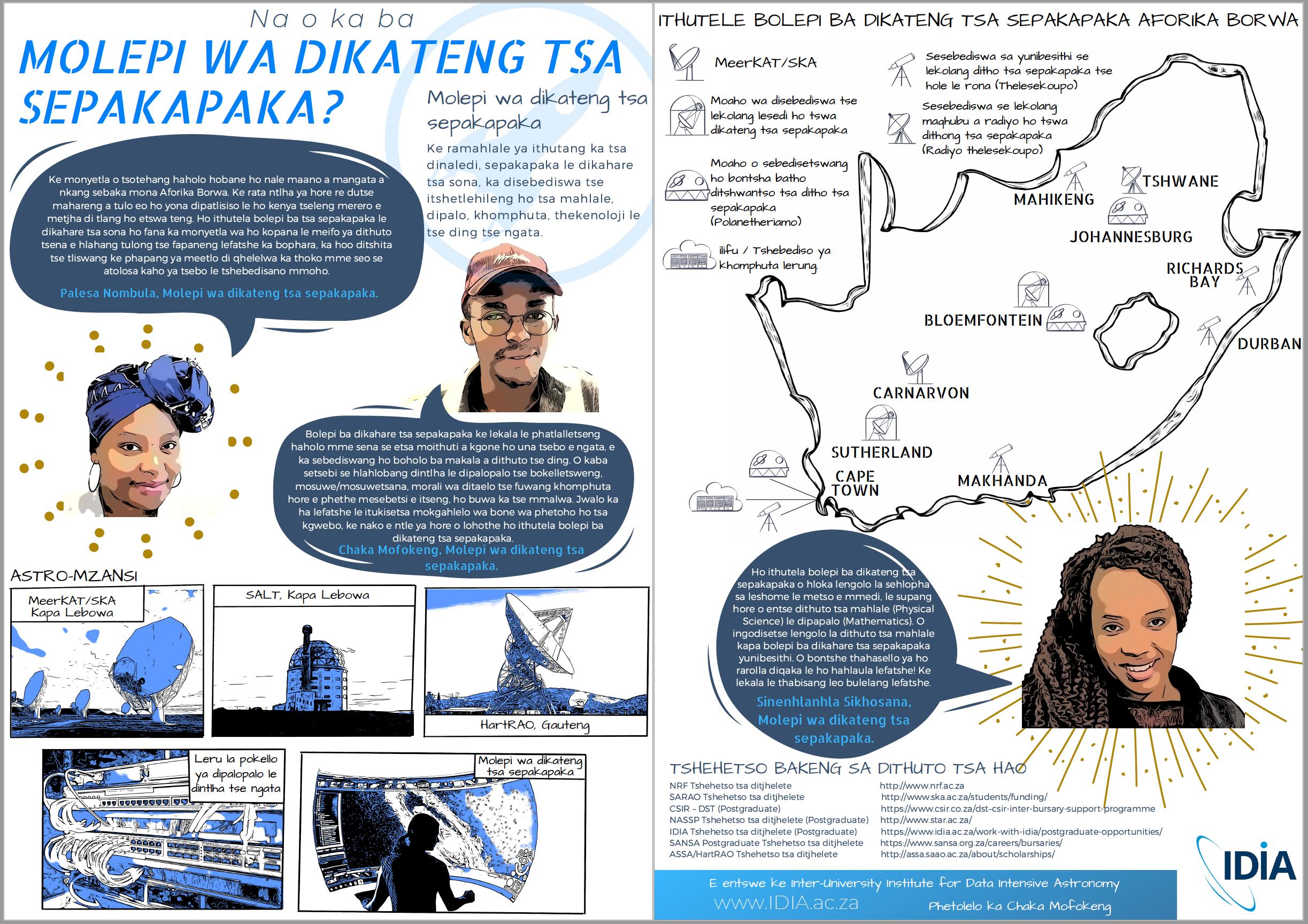

For the past year, he has been working with an associate professor in the astronomy department, Doctor Carolina Ödman, to translate some of the resources they provide to high school students in the townships of Cape Town to introduce them to astronomy. He translated the resource from English to Sesotho himself, but he has now joined forces with a masters student from the Department of Xhosa to expand the project. Their vision is for the material to reach scholars in township and rural schools in particular and to keep translating to invite as many of South Africa’s linguistic communities into astronomy as possible.

Ödman started this venture with a simple request on social media: that people translate the resource she had designed to inform and encourage high school students to seriously consider a career in astronomy. She received it back in Setswana, Afrikaans, Spanish, Romanian – and a Sesotho version from her student, Mofokeng.

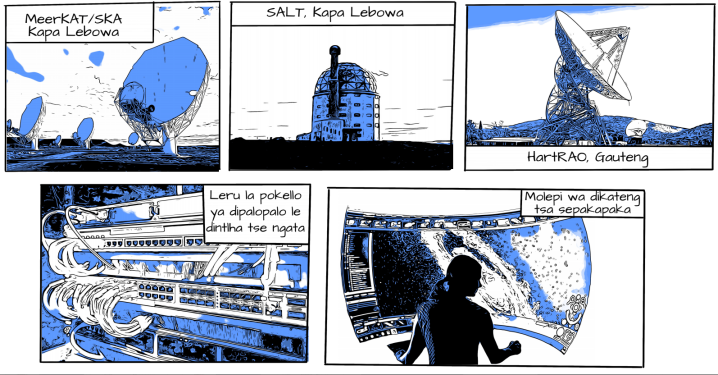

The English version of the guide Dr Ödman designed to introduce high school students to astronomy. (Source: Carolina Ödman)

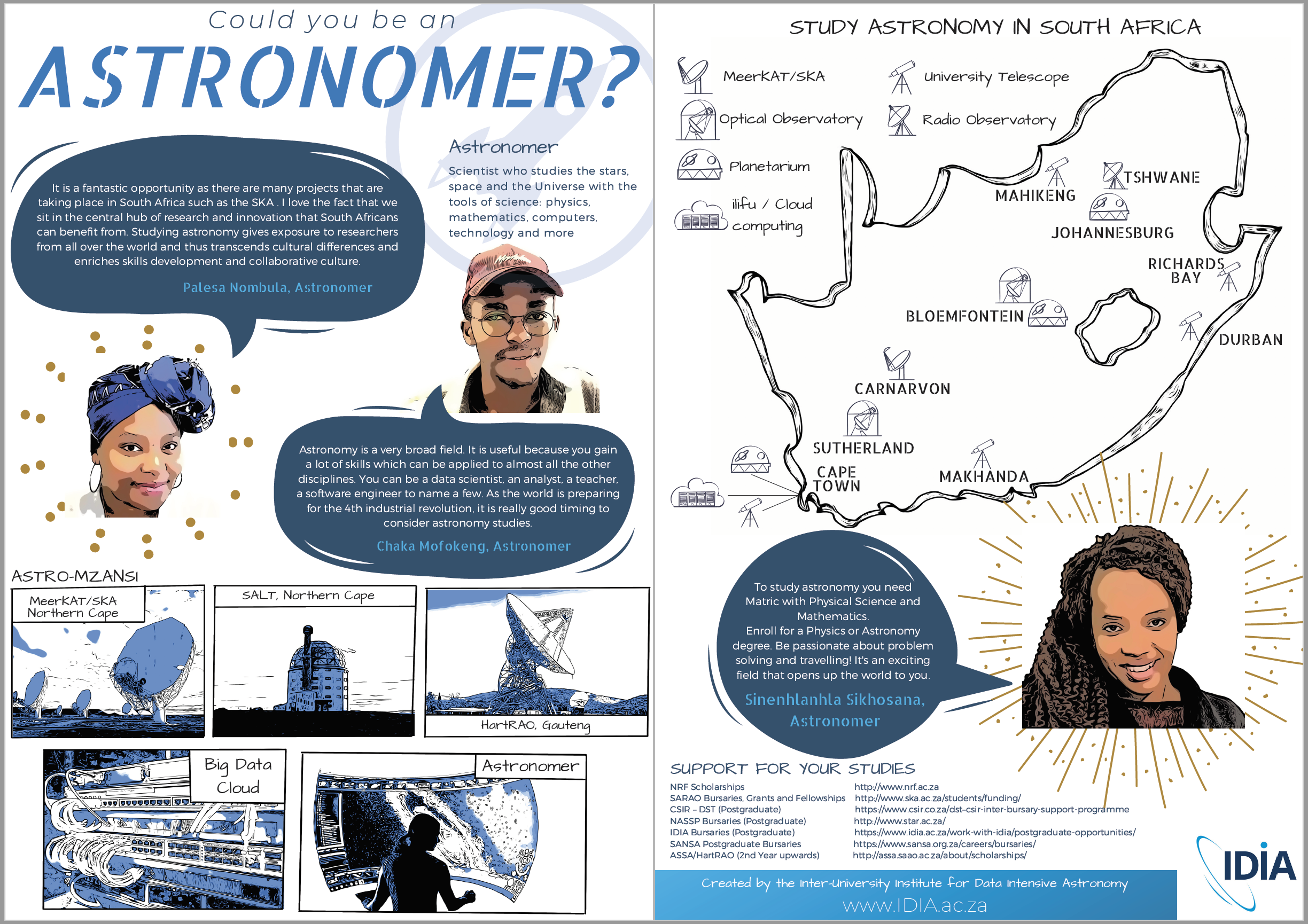

The Sesotho version of the guide Dr Ödman designed to introduce high school students to astronomy. It was translated by Chaka Mofokeng, who is about to start his doctorate in astronomy. (Source: Carolina Ödman)

She runs the outreach and development arm of the Inter-University Institute for Data Intensive Astronomy and and when she developed this updated, illustrated guide she thought it would be “silly” not to translate it into indigenous South African languages.

“What Chaka did beautifully is instead of taking the few technical astronomy terms that were there [in the pamphlet] and just using the English, he actually expanded them into a whole explanation. I thought: this is the way to do it,” recalls Ödman.

The scholars of Mofokeng’s old high school, Leseding Technical Secondary School, were surprised when they were handed a booklet about astronomy in Sesotho. Mofokeng said they were familiar with the words but hadn’t seen them used in the context of astronomy. People on Twitter had the same reaction and instantly offered their help in future projects.

Mofokeng himself had this experience when he did the translation. “I realised during my first translation of the resources into Sesotho that I always knew about these words but had never taken care to notice that they actually mean the same thing as the English counterpart,” he says.

Through Ödman and the head of the university’s Department of Xhosa, Dr Sebolelo Mokapela, he was introduced to Sinethemba Nobom who is doing a masters in Xhosa at the university. In fact, the process of translating resources for the astronomy department has become the focus of his thesis.

Although a language student for many years, Nobom too encountered words he knows, but came to know in a new unexpected way when he began this translation. He and Mofokeng constantly converse about what words truly mean, whether by WhatsApp, phone call or on campus.

Mokapela explains that a translator cannot work in isolation. The translator will receive the “source text” from a client and then assess who the audience is and the best way to speak to them.

They consult with an expert, which in this case is Mofokeng, who can help them to understand the technical terms accurately. Once the first translation is complete, the text is edited to ensure equivalence to the original.

It is then proofread, and then read again and translated back into the original language and compared to the source text. If the messages match, then the translation can be shown to a sample of the audience. If they give it the go-ahead, it can be released.

As Nobom and Mokapela point out, translation is not a process of creation, but is also not about simply finding equivalents.

“Translation is a cultural exchange. It’s not merely a document you must translate by finding equivalent words. It involves a cultural dimension. Every language says something about the universe,” explains Nobom.

Nobom scours books, listens to radio and discusses words with elders to try to get to the language the Xhosa-speaking scholars can relate to. It already exists – he just needs to access it.

“Some of the things our elders do know of, like the names of the stars. We have that in our language – it’s just that when having to talk about it in English, we sort of see it as a difficulty or fail to understand. When we put it in the language that we’ve had before, it then makes more sense,” he says.

For Mokapela, using this existing, familiar language is crucial to the success of the translation.

She explains that in her experience, taking the information to a community in isiXhosa instead of the English version is more likely to spark curiosity in a child.

“Chaka is one of the very few who out of curiosity would want to know about this, but how many are like him? Now that the information is going to be given to them in isiXhosa, then it will say in their mind that the reason why this is being given in isiXhosa is because it is for them – they must go and do this and be an astronomer too.

“It invites them: come and be part of us. We have space for you by providing this information in their language. Come, you are one of us. You are not different. You can also make change. Prove to people that this is for everybody. That’s how I look at it,” she says.

For her, this project is part of the broader movement towards transformative linguistic justice where all of South Africa’s languages operate as equivalents in society.

For the rest of the team this, together with the decolonisation of the sciences and education, is the broader mission at hand.

Mofokeng notes that there has been a lot of discussion about the decolonisation of education recently, but never before has anyone gone to this length to translate material about the sciences for high school students in such a meaningful way.

“I get the feeling that this project works towards decolonisation. We are not just adapting the language or taking a direct translation, but digging deeper and even into our culture, so it’s actually going towards that,” he explains.

This has been Ödman’s motivation all along. “Scientific terms are also colonial and carry the colonial history… It’s something that as a science community we need to be sensitive to and as we seek to make science available in other languages we need to take the opportunity to refresh it and remove colonial references and reference the science better,” she says.

All are adamant that this is just the beginning of a much larger effort to translate astronomy resources and vocabulary into as many languages as possible and to spread them far and wide.

There seems to be an appetite for it – printouts get picked up “like hotcakes” and they have been inundated with interest. For now, the guide will be available online and at schools around Cape Town.

Ödman says it seems to touch something very deep.

“I think maybe it’s in the approach, because I’m not sure that science is generally seen as being humble and as acknowledging its colonial history. I think this is really where we come from, that science has to be humble and it has to be inclusive. If we want science to mean anything for this country, it has to be done by people from this country and we can’t be an elite practice. We really have to make it available,” she says.

Mokapela echoes this sentiment. Her hope is that the resources can be taken to rural areas so that no one is left out.

“Yes, it is long overdue, but I am happy that we are working with astrophysics and making this information accessible to all the communities, especially isiXhosa for now, and opening these doors for the indigenous communities of South Africa.”

Ödman reckons that with time and effort there can be a national project to create advanced science vocabularies in South African languages which are made up of words which “… convey not just scientific knowledge, but science as something which is owned here and is meaningful here. It must be something we can talk about without having to use borrowed terms. Then, I think we have something huge.”

Nobom says he will have peace of mind when his thesis is done. He hopes that his small contribution will be built upon by other translators too.

“This work is going to take generations – it’s a harsh reality. It is going to take generations for it to reach a level where isiXhosa can be used as a language which is equivalent to English.” MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider