MAVERICK LIFE: Remembering Santu Mofokeng

World-class photography, born under the roof of apartheid

Santu Mofokeng experienced life as violent, tragic and futile. His photographs make a persuasive case for his inclusion in the pantheon of greats. Not just in SA, but globally.

In 2007, 13 years before his death on 27 January 2020, photographer Santu Mofokeng phoned and thanked me for the “nice obituary” I had written. He was referring to a short profile in the Sunday Times that coincided with his travelling survey exhibition, Invoice, at the Standard Bank Gallery, Johannesburg. He laughed. Mofokeng often laughed. It frequently punctuated the narration of his self-organised survey of photos describing everyday life in Soweto, rural serfdom in Bloemhof and the spiritual malaise occasioned by the demise of apartheid, that “impossible ancestor,” as he described it.

One laugh bears recalling. It bookended his narration of Train Church (1986), a now-celebrated series of close-up portraits of religious worshippers shuttling in and out of 1980s Soweto on crowded passenger trains. “I call it a project,” Mofokeng said during a public walkthrough of Invoice in reference to this breakthrough series, “but I was just a journalist making pictures.” Mofokeng recalled colleagues at Afrapix, the activist photo collective he joined in 1985, saying they “weren’t journalists but documentarists doing projects”. This earnestness was still a source of mirth for him in 2007. His uncontained laughter pealed through the gallery.

Mofokeng died from progressive supranuclear palsy, a degenerative illness that stole away his life in increments. First his voice and laugh, around 2014, followed by his ability to walk, and finally his cognitive abilities. Rather than think of the wraith I saw seated one day in a Rosebank gallery, a sallow-faced man reduced to communicating via SMS, I prefer to remember the laughter.

Laughter was both a palliative and seditious weapon for Mofokeng, who graduated from Soweto street photographer to darkroom technician to 1980s news photographer to a man with a “project” in the early 1990s. The immensity of that project was heralded by his self-organised survey of his work, Invoice, which premiered at Cape Town’s South African National Gallery in 2006 and travelled to London in 2009. As was his habit, Mofokeng wrote a short text to accompany this exhibition of photos.

“Apartheid was a roof,” he stated. “And under this roof life was difficult, many aspects of life were concealed, proscribed. People tried to live their lives in dignity but their joy was tainted with guilt and defiance.” The demise of apartheid, he added, had “brought to the fore a crisis of spiritual insecurity for the many who believe in the spiritual dimensions of life. Today, this consciousness of spiritual forces, which helped people cope with the burdens of apartheid, is being undermined by mutations in nature. If apartheid was a scourge the new threat is a virus; invisible perils both.”

Among the loosely grouped photos on Invoice condensing this big-picture insight into singular photos was a head-and-shoulders portrait of Mofokeng’s older brother, Ishmael. Titled Eyes-Wide-Shut, Motouleng Cave, Clarens (2004), the photo was taken in a Free State cave shortly before Ishmael’s death from Aids-related complications. Much like Soweto, Ishmael provided ballast for Mofokeng in a world he variously understood and experienced as violent, tragic and futile. The loss of his brother was the source of immense pain and confusion for Mofokeng.

Santu Mofokeng (b 1956)

Eyes wide shut, Motouleng Cave – Clarens (2004)

©Santu Mofokeng Foundation

Images courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

Born in 1956, Mofokeng was the tenth child of Johannes Mofokeng and the sixth born to his mother, Martha. Johannes died in 1960, and so Ishmael came to fill the vacuum of a role model. Ishmael was good with a knife and an expert at judo, but shunned fighting. As an adult, he devoted himself to spiritual practice and became a traditional healer. Ishmael is an unavoidable protagonist in any reckoning of Mofokeng’s life.

He forms the subject of the final book of the photographer’s magnum opus, Santu Mofokeng: Stories (2019). Distilled from an archive of approximately 32,000 frames, this 21-volume anthology tracks Mofokeng’s work from 1985 to 2013. It offers a major restatement of the photographer’s career. In a country where Peter Magubane and David Goldblatt are revered as icons of concerned photography, the 581 photographs in Stories make a persuasive case for Mofokeng’s place in the pantheon of greats. Not just in South Africa, but globally.

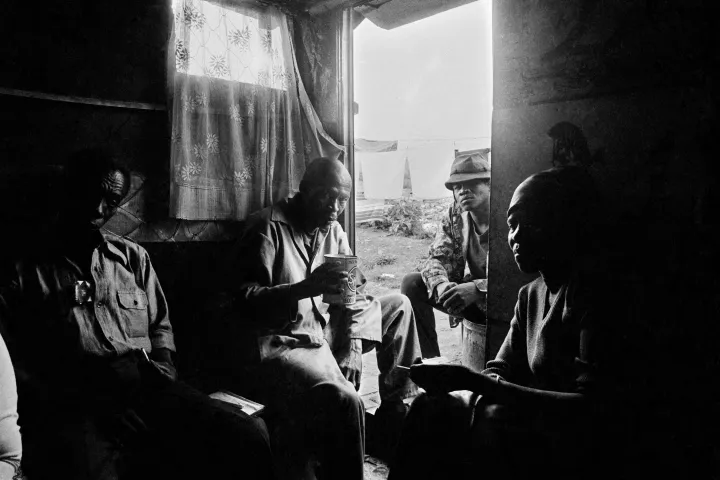

Santu Mofokeng (b 1956)

Winter in Tembisa (c.1991)

©Santu Mofokeng Foundation

Images courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

Santu Mofokeng (b 1956) Police with sjamboks, Plein Street (c.1986) ©Santu Mofokeng Foundation Images courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

“Given the quality and quantity of what is included here, Mofokeng deserves top tier international renown,” wrote New York photo critic Loring Knoblauch last year in a review. Full-blown acclaim in New York eluded Mofokeng, although elsewhere, in Europe, he was heralded as a great. In 2002, Mofokeng’s photography was featured in Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor’s landmark Documenta 11 exhibition in Kassel, Germany.

Enwezor was instrumental in showing Mofokeng’s The Black Photo Album/Look at Me: 1890–1950, a slide-show exhibition of found studio portraits commissioned by members of 10 black, working- and middle-class families. This archival project grew out of Mofokeng’s decade-long association with the Institute for Advanced Social Research at the University of the Witwatersrand, where he worked as a visual anthropologist and researcher under the mentorship of social historian Charles van Onselen. It is how Mofokeng came to make photos in Bloemhof.

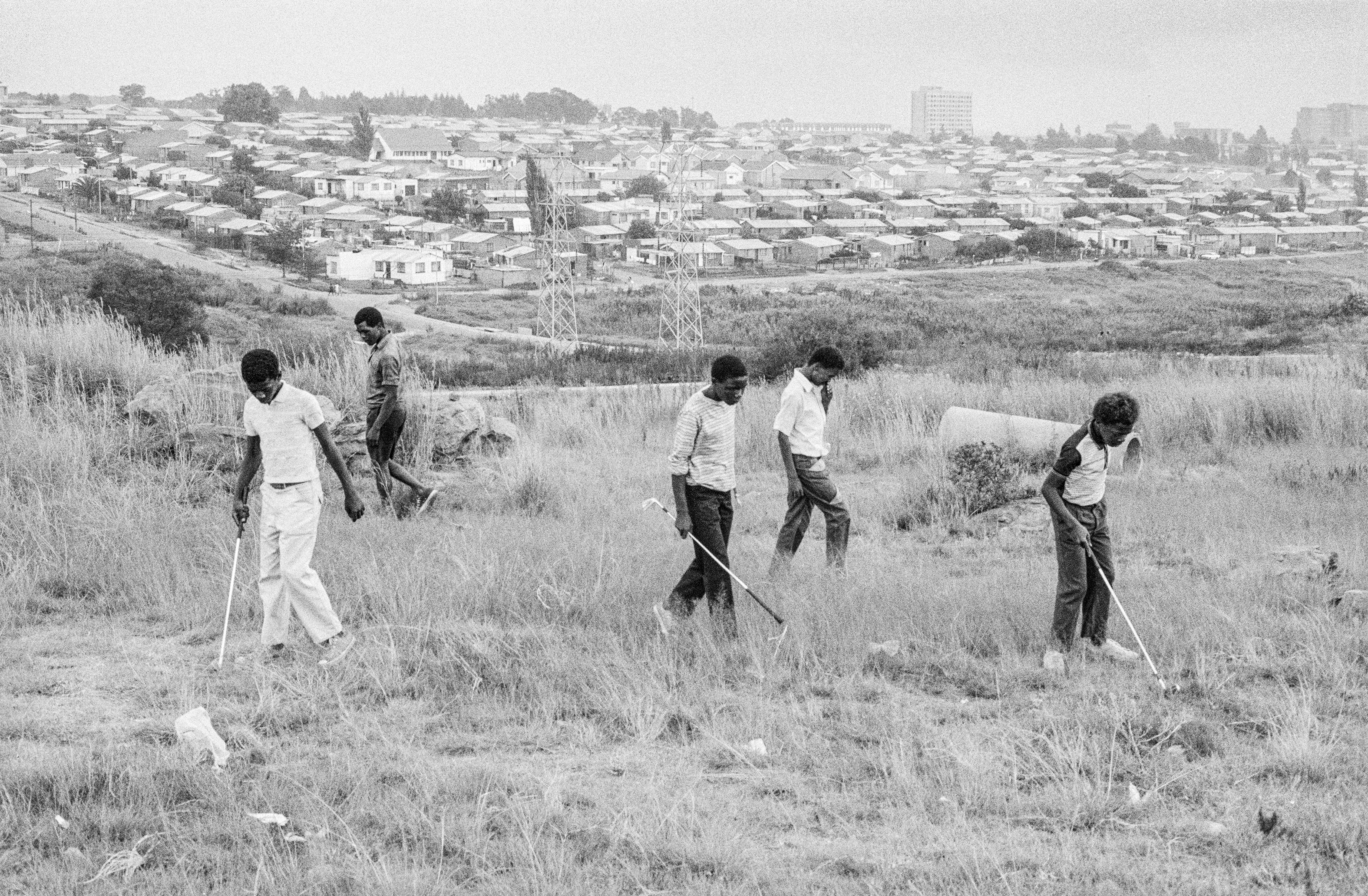

Santu Mofokeng (b 1956)

Fairways, Golf in Zone 6, Diepkloof, Soweto (c.1987)

©Santu Mofokeng Foundation

Images courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

Santu Mofokeng (b 1956); Afoor family bedroom, Vaalrand (1988)

©Santu Mofokeng Foundation

Images courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

Alongside The Black Photo Album, Mofokeng is best known internationally for Chasing Shadows (1996-2014), a photographic essay largely composed in the caves of central South Africa. The naming and coherent articulation of this latter project largely stems from Mofokeng’s association with French art historian Corinne Diserens, who in 2011 organised the first international survey of Mofokeng’s work, Chasing Shadows: Santu Mofokeng, Thirty Years of Photographic Essays (2011), at Paris photography space Jeu de Paume.

Comprised of some 200 photographs, Diserens argued that the photographic essay, with its emphasis on “complexity,” allowed Mofokeng to recover ambiguity and nuance in the portrayal of black South African life. Interestingly, the exhibition featured new landscape photos made in colour. In 2013, Mofokeng was invited to show alongside Chinese artist Ai Weiwei in the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. He presented an excerpt of The Black Photo Album alongside new colour photos of graves and mining sites, as well as an unseen colour photo of the cave where Ishmael had sought consort with the ancestors.

Although best known for his chiaroscuro views of late-apartheid and early post-apartheid life, colour is not coincidental in a reckoning with Mofokeng. In 2013, a few months after I saw the photographer stuffed into a blazer at the opening of the Venice Biennale, I reached out to him for comment. Photographer Zwelethu Mthethwa has just been arrested on charges of murder. Mofokeng’s response is worth elaborating as it describes the complexities of the nebulous cultural world he negotiated throughout his career, one that celebrated and ignored him with equal force.

Mofokeng admitted to holding a “complex view” of Mthethwa. Some of that complexity surfaced in an incident in a small Shinjuku eatery in Tokyo. Mofokeng was part of a cohort of South Africans, Mthethwa included, exhibiting at Tama Art University in 2004. Eating tempura and drinking beer one afternoon, Mofokeng turned to Mthethwa, a convicted murderer who once represented the vanguard of new South African photography with his colour portraits of shack dwellers, and said: “Chris Ledochowski takes much better township photos than you.” Mofokeng was ribbing Mthethwa. He laughed.

“I last met Zwelethu in Tel Aviv where he said something I found to be very strange,” Mofokeng continued in his email from 2013. “He told me, many people wished us to be enemies. Of course, I suspect I know why. Our practice and our approach to photography are antithetical.” Mofokeng admitted to admiring Mthethwa’s image as a self-made dandy in a Porsche. “Zwelethu destroys the myth of the poor black artist. He flaunts that he is successful and he has money and this has the tendency to rub people the wrong way. Why I like his attitude is it encourages the youth to see documentary photography as a vehicle to take up in order to make a living.”

But that’s where his respect ended. Mofokeng disliked Mthethwa’s strategic valorisation of colour as a marker of post-apartheid photography. In particular, he thought Mthethwa’s argument that “colour dignifies” specious. When he read Mthethwa’s claim that black and white photography “was used to deny (rob) black people of dignity, I felt that my work and that of lefties, groups and archives and other activists and organizations, along with their efforts were being insulted and thrown out like so much apartheid paraphernalia and baggage.” He read this as a personal attack. “As a past member of Afrapix, I felt our efforts in fighting and agitating for apartheid to be disbanded and abandoned were being rubbished.”

What constitutes the meat of an adequate obituary? Quotes by eminent nabobs that affirm the validity of a life juxtaposed against broad platitudes about struggle and triumph? Gossip proposed as needless muckraking?

Santu Mofokeng’s life exceeded the clichés of his hagiographers. He was a complicated man, and admitted as much in a magisterial essay appearing in his first book of photographs from 2001. Mofokeng was a man of our messy present. I once wrote to him, in 2014, that his undiagnosed silence was punishment for being sassy. Actually, I wrote tjatjarag. He liked that, he replied. “Tjatjarag is my photography. I have been doing it for almost my entire life. Why is it now talking so loud, I wonder.” ML

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of Maverick Life delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider