BOOK EXTRACT

Eden Lost, and Regained: How one man saved the Kruger National Park from being lost forever

AP Cartwright’s book ‘Spoor of Blood’, published under the pseudonym, Alan Cattrick, the classic history of the bloody slaughter of southern Africa’s wildlife by a succession of hunters, has been reprinted. What follows is an extract, preceded by a necessary explanation of the work’s style and place.

In 1957, the board of the Rand Daily Mail fired the editor, AP (Paddy) Cartwright, for similar reasons to the later firings of Lawrence Gandar and Allister Sparks – his political stance was viewed as being too liberal. Cartwright, a prolific author of 19 books, used his forced temporary retirement to write the classic history of the bloody slaughter of southern Africa’s wildlife by a succession of hunters, Spoor of Blood, published under the pseudonym, Alan Cattrick. The book was ultimately a tribute to the handful of men (they were all men) who saved South Africa’s decimated wildlife by establishing the modern-day Kruger National Park, under its first and perhaps most famous warden, James Stevenson-Hamilton. Now it has been reprinted under AP Cartwright’s own name, as Eden Lost, and Regained by Footprint Press. In this extract, Cartwright describes the seemingly impossible task Stevenson-Hamilton faced in taming what had until then been a hunting free-for-all. Ironically, many of the threats to the park that existed then – among them mining, farming, water extraction and poaching – still exist today.

Written in the late 1950s, the book would in places be considered politically incorrect today, with its references to forced removals, “natives” and “boys”, among others. But it is an invaluable historical record, and in his foreword, Cartwright’s son Tim writes, “Paddy Cartwright was always on the side of the underdog and did not have an ounce of racism in his makeup. If some of the old phrases, no longer correct, appear in this reprint it is simply because it can be difficult to replace them with appropriate words – and the terms were in everyday use by most of the characters described in this book.”

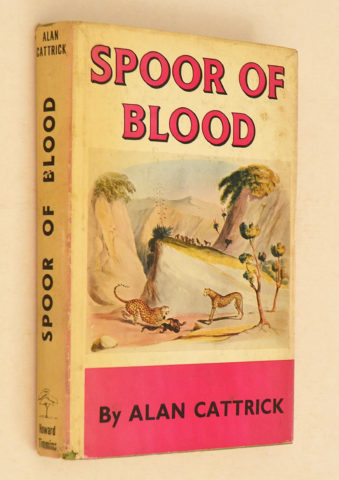

Spoor of Blood (Photo: supplied)

Of the men who sent Stevenson-Hamilton to Sabie in 1902 not one had ever set eyes on the territory he was to control. Even among the burghers of the South African Republic there were few who had been there.

In 1838 Louis Trichardt’s party of Voortrekkers had crossed the area near Pretorius Kop in their disastrous march to Lourenço Marques. Earlier than that the Van Rensburg trekkers, 49 of them in all, had trekked into what is today the northern sector of the Kruger National Park. They were also bound for Lourenço Marques and they followed the course of the Pafuri River.

These events had given the Sabie area an evil reputation. It was the “white man’s grave”, a district where there was a particularly noxious brand of fever and where the tribes were hostile.

The Portuguese had explored there much earlier. There is an account by De Kuyper of an expedition from Lourenço Marques which reached Komatipoort in 1825 and which fought a skirmish with the native inhabitants somewhere near the present Crocodile Bridge and then retreated to the Lebombo mountains. Some fifteen years later an Italian named João Albasini, who had become a Portuguese subject, settled on the banks of the Sabie River and lived there for many years.

João-Albasini. (Photo: supplied)

I should like to be able to tell you Albasini’s story, but the records are vague. He seems to have combined the qualities of Prester John with some of the weaknesses of King Solomon. He built himself a mansion in the wilds, organised teams of trappers and hunters and did a roaring trade with Lourenço Marques. He acquired huge herds of cattle, laid out orchards, planted coffee trees and generally made himself comfortable. In the end he became virtually the white chief of the tribes between the Crocodile and Sabie rivers. A most remarkable man, and one whose name stands very high on the list of traders and adventurers who opened up Africa.

The South African Republic was naturally anxious to establish a route to the port of Lourenço Marques and made several attempts to explore the territory. Karel Trichardt, Louis Trichardt’s son, led the expedition that finally trekked through to the coast and, it seems probable, followed the route that Albasini’s porters had established in their journeys from the Sabie River to Lourenço Marques. The first discovery of gold at Lydenburg in 1869 led to the building of the first real road, if road it could be called. AH Nelmapius, a Hungarian, appeared upon the scene and with the approval of the Transvaal government, established a transport company to operate between Lydenburg and Lourenço Marques. He began by transporting goods up the Komati River in barges as far as the foot of the Lebombo Mountains. From there hordes of native porters carried them as far as Pretorius Kop, whence they were loaded on to wagons and taken on to the goldfield. As malaria killed white men who crossed what is now the game reserve and the tsetse fly killed oxen, native carriers were regarded as the most economical means of bridging the gap. They were supposed to be immune from any form of fever. Nelmapius’s reward for this service to the republic was the gift of a number of farms along the road, some 10,000 morgen in all, on which he established camps for the caravans.

This route eventually became the wagon road to Lydenburg which Percy Fitzpatrick immortalised in Jock of the Bushveld. The transport men used to make a night dash from the Crocodile River to Ship Mountain to avoid the tsetse fly (which does not attack its victims after dark). But the sight and smell of the oxen sweating at the yoke were too much for the lions which scouted along the wagon track and eventually they grew so bold that they attacked the wagons. The old road, overgrown and almost concealed in the undergrowth, was still to be traced when Stevenson-Hamilton took over some thirty years later. It is no exaggeration to say that it was paved with the bones of native carriers, oxen and some of the white transport riders who died in taking the wagons through.

James Stephenson-Hamilton.

Hendrik Potgieter, one of the Voortrekker leaders, settled near Lydenburg as early as 1843 and round him grew up a Boer community of solid, hard-working farmers who counted this the finest area in the Transvaal. The Lowveld became their hunting ground. Every winter they made expeditions along the banks of the Sabie and Olifants rivers and found a paradise of game. From this community sprang a well-remembered figure in South African history in the person of Abel Erasmus, whom the republic appointed native commissioner of the whole area as far as the Portuguese border. Erasmus was far more than a mere native commissioner. In fact it would be more accurate to describe him as the governor-general” of the Lowveld. He spoke the languages, knew every chief between the Letaba and the Crocodile and bluntly told them what to do and what not to do. His word was law and he was venerated by the tribes even as far as Swaziland. He was also a first-class rifle shot and a great hunter.

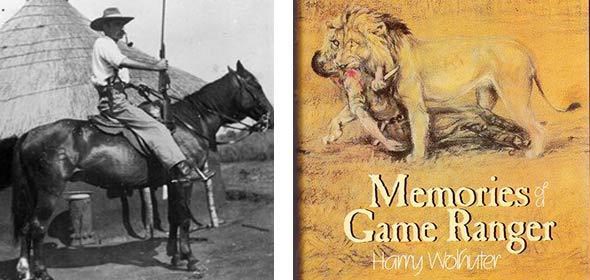

In addition to the Boer hunters there were a number of men who combined trading, raising cattle and hunting as a means of making a livelihood. Among them were Henry Glyn, the Sanderson brothers, Francis, David Schoeman and, later in the day, young Harry Wolhuter. Add to these the hunters who came for a season and then moved on, pursuing the dwindling herds of elephants, and you have the whole list of the hundred-odd men who knew the Sabie reserve.

Of all these men only Albasini had actually settled in the “fever belt” so that when Stevenson-Hamilton decided that, come what might, he must live among his charges, he was the second white man in history to become a permanent resident in this no-man’s-land. At the point on the Sabie River where the Selati Railway line came to an abrupt halt (it was known as Sabie Bridge though, in fact, the bridge had not been completed) there was a blockhouse built by the men of Steinacker’s Horse who had been stationed there. It was an unpretentious building of brick and corrugated iron but it had one advantage that caught Stevenson-Hamilton’s eye.

Someone had built on to it an “observation post” which commanded a view up and down the river and which received the full benefit of such breezes as there were. This, he decided, was where he wanted to live and he moved in. The old-timers warned him that he would not survive. He must leave the river every summer when the rains and the fever came, they said. He would certainly get a fever and might expect to die of “blackwater” in a year or two. He ignored these warnings and lived there for forty-four years (though not in the same building, of course). The headquarters of the administration of the Kruger National Park are there to this day.

On that little verandah above the river, Stevenson-Hamilton had his meals and there, when he was not in his office” (a rondavel with a thatched roof that he built nearby), he sat in the evenings brooding over his problems… And what problems they were! Imagine yourself set down in a spot such as this, in the year 1902, with instructions to establish a game reserve. You have no money worth mentioning, no staff and no amenities within fifty miles. You have 1,200 square miles of wild country to control and your transport consists of an ox-wagon, some donkeys and a couple of horses. There are anything up to five thousand primitive Africans living in the area, most of whom have to be removed. There are poachers, both white and black, who must be arrested and punished. But you have no powers of arrest or legal authority to punish them. You are not even sure where the boundaries of the reserve begin and end…

There was no textbook on the management of game reserves. No one had ever tried such an experiment before. This was the first wildlife sanctuary in Africa and he the first “head ranger”. There was nothing for it but to write the rules as he went along.

He began at once. As soon as the newly appointed rangers were at their posts he trekked to Komatipoort and took the train to Pretoria. In his pocket was a set of draft regulations which would give his rangers powers of arrest and authority to expel from the reserve anyone whom they considered undesirable. But that was the least of his demands. Much more startling was his plan for enlarging the reserve by taking in all the land between the Sabie and Olifants rivers and then extending the whole protected area as far as the Limpopo by adding to the reserve all the State lands north of the Letaba river to the Transvaal border. Even that was not all. He wanted the western border, between the Sabie and Crocodile rivers, pushed out a further twelve miles to take in the excellent grazing country in the foothills of the Drakensberg and to provide a buffer strip between the heart of the reserve and the towns and rapidly growing farming areas of the Lowveld.

All he was asking for, in fact, was an extra 12,000 square miles of the borderlands of the Transvaal!

While Sir Godfrey Lagden and his staff were studying the details of this plan (and presumably wondering whether they had appointed yet another eccentric to the post of chief ranger) he went to Johannesburg and interviewed the owners of all the farms in the Olifants river area. He pleaded the cause of game conservation and managed to persuade them all to sign an agreement by which they allowed government control of their land for a period of five years. In return, the staff of the reserve was to protect their farms, prevent prospecting and look after the fauna and flora. With this agreement signed (he did it all in ten days) he went back to Pretoria and talked the administration into giving him what he wanted. At some stage of the proceedings, he also managed to abolish the title “chief ranger” and became the warden.

This was the first of Stevenson-Hamilton’s triumphs in getting civil servants to see eye to eye with him. How he did it we shall never know. The man had uncanny powers of persuasion which he was to exercise throughout his life but he never won a greater victory than this one. In these negotiations, undertaken barely six months after his appointment, he succeeded in obtaining a corridor of wild country which gave the game free movement between Portuguese territory and the Transvaal. He had, in fact, established today’s Kruger National Park and it was done by striking while the iron was hot. Five years later, even three years later, it would have been impossible to persuade the Transvaal government to give away such a large area of State lands. Ten years later, even had it by some miracle been possible to persuade the administration to hand over part of the area, the cost might have been well over £1,000,000. Thus South Africa gained its greatest national asset at the cost of a railway journey from Komatipoort, some hours of steady talking by Stevenson-Hamilton and a little paper and ink. In after years, there was a bill to be met when the private landowners were bought out by the State, but it was a fraction of what it might have been. Stevenson-Hamilton’s vision and his determination had won a victory for generations yet unborn.

The first poster advertising the game reserve, by renowned artist Stratford Caldecott. (Photo: supplied)

It did not happen all at once, of course. It was many months before the new regulations were promulgated and much longer before the Shingwidzi country north of the Letaba was proclaimed a reserve. But the fact is that Stevenson-Hamilton, who had taken up an appointment as chief ranger of a game reserve of 1,200 square miles in July, 1902, found himself in charge of an area of 14,000 square miles little over a year later. By that time he had five white men scattered through the area and fifty native rangers assisting them. His rangers had the right to arrest trespassers and poachers within the boundaries of the reserve and he had been appointed a special Justice of the Peace, with power to try cases of poaching and inflict the necessary penalties. This obviated marching prisoners to Barberton or Lydenburg magistrates’ courts, five days’ journey away in those days and an impossible procedure.

While the administration of the reserve was taking shape Stevenson-Hamilton proceeded to show in no uncertain way that he meant business. He received a report that a party of very senior police officers, including the deputy commissioner, in two ox-wagons and accompanied by a white guide and a number of orderlies, had trekked through the reserve to the Portuguese border. Native rangers reported that, in the area south of the Olifants river, they had shot a giraffe and a number of wildebeests. Though the country here had not yet been proclaimed part of the reserve a ban had been placed on all shooting in the area and this had been displayed in the Government Gazette, required reading for all police officers.

By this time Stevenson-Hamilton knew his Lowveld. He knew that, remote and sparsely populated as the area might be, there was as much gossip among its inhabitants, white and black, as in any garden city. Everything this police expedition did would be faithfully reported by the grapevine and discussed for years afterwards.

His reputation would depend upon what action he took to investigate this infringement of the regulations. But even had that not been the case he was not the man to put up with the sheer effrontery of this expedition into the reserve without so much as a chit to the warden. I suspect that he was in a white heat of rage.

He sent Harry Wolhuter off to investigate the reports that had been received at Sabie Bridge and to question the police officers. It was on that expedition that Wolhuter had his encounter with a lion, a story that is now part of South African history. A lion sprang on to Wolhuter’s horse from behind, and the terrified animal threw its rider. Another lion, which had been crouched nearby, seized the ranger by the shoulder and carried him off, his legs dragging along the ground under its belly. Wolhuter managed to get his left hand to the sheath-knife he carried, drew it and, stabbing upwards, drove it into the lion’s heart and its throat. The lion dropped him and slunk off into the bush to die while Wolhuter, despite his fearful injuries, hauled himself up into a tree. There his boys found him and took him to Komatipoort. He was then sent by train to the Barberton hospital where, thanks to a magnificent constitution, he recovered and lived to serve the game reserve faithfully for another forty-three years.

Harry Wolhuter. (Images: supplied)

He tells the story better than anyone else can in his book and in all the long history of hunting in South Africa there is nothing to equal the cold courage of this tale of a young man, desperately wounded, who killed a full-grown lion with a sheath-knife. When in his letter to me the other day he said that his lion-bite” shoulder was worrying him, he was 84.

By the time Stevenson-Hamilton heard of the disaster that had overtaken Wolhuter it was too late to intercept the hunters. However, another ranger who was sent to the spot cross-examined all the available native witnesses and established beyond doubt that a giraffe had been ridden down and shot and that a number of animals had been killed. With this evidence in his hands, Stevenson-Hamilton went into Barberton and laid a criminal charge against the two most senior police officers in the Transvaal.

Probably only an attempt to prosecute the chief magistrate of Johannesburg could have caused a greater flutter in the civil service of the Transvaal. Because the principle for which he was fighting was not understood, there was very little sympathy for Stevenson-Hamilton. If a senior police officer could not shoot in a game reserve, who could? And what was a game reserve for if not to provide a little shooting for the brass-hats? Of course, there had to be regulations against poaching, but these were meant to apply to natives. It was ridiculous to call the deputy commissioner of police a poacher. The man was getting too big for his boots.

The wheels of officialdom began to turn. The man must be persuaded to drop the charge.

At a luncheon given by Lord Milner, which he attended on one of his visits to Pretoria, Sir Alfred Lawley, the Lieutenant-Governor of the Transvaal, asked him whether he was quite certain that the evidence showed that the officers had actually committed an offence. Another official told him that it was being said in Pretoria that the prosecution was a “vindictive” one. Clearly he was being given every opportunity to backpedal.

But Stevenson-Hamilton was deaf to all hints, subtle or otherwise. He had collected the evidence and laid the charge. It was now up to the authorities to see that the law was carried out. There was a delay – a very long delay. But at length, nine months after he had laid the charge, he was informed that the men would appear in the magistrate’s court at Pietersburg, which was the district in which one of the officers exercised authority. The case was duly heard. Ranger De la Porte gave his evidence and native witnesses were called. The defence, I gather, was that the officers were genuinely under the impression that they were in Portuguese territory and not in the area governed by the game reserve regulations. The magistrate imposed a fine of £5 on one of the officers for shooting a wildebeest in the protected area. He found, however, that there was reason to doubt whether the giraffe had been shot in that area or on the other side of the Portuguese border.

As the giraffe was killed close by I could never quite make out exactly how the magistrate managed to convince himself that its death might have happened across the frontier,” commented Stevenson-Hamilton afterwards.

The prosecution, and the humiliation of the court proceedings, did not endear the warden of the game reserve to the senior officers of the South African Constabulary (even the police in those days had not yet grasped the ideal which he had tried to establish). But, if for some time thereafter there was a cold war” between the police and the staff of the reserve, it was well worth this inconvenience. The newspapers, as far as I can discover, missed this cause celebre. But the Lowveld grapevine fairly trembled with excitement. There was not a white man or a native between the Letaba river and the Swaziland border who did not know that the big chiefs” of the police had been caught poaching and had appeared before a magistrate. The moral effect of those proceedings was to last for the next ten years. Stevenson-Hamilton had effectively demonstrated that there was one law for all, and that there would be no exceptions to it. His stubbornness in seeing the prosecution through won him the respect of the whole population. And, even more important, it established respect for the game laws.

South African Eden, by J Stevenson-Hamilton. (Photo: supplied)

The Shangaans, who had their own name for every white man in the district, had already christened him “Skukuza”, a title which may be liberally rendered in English as “he who reorganises” but which, taken literally, means “he who turns everything upside down”. When they heard that he had “tried to put the big baas of the police in jail”, they must have decided that they had chosen the right name!

In the winter of 1903, Sir Godfrey Lagden felt that it was time he visited Sabie and found out what that mysterious sub-section of his department headed ”game reserve” was doing with the money he supplied it from time to time. Accompanied by a retinue of officials of the Native Affairs Department he set out for Komatipoort. There the sole surviving locomotive of the Selati Railway Company was hauled out of its shed and put into training a week before the official party arrived. It puffed its way to Sabie Bridge drawing a special coach in which the distinguished visitors made themselves as comfortable as possible. Stevenson-Hamilton was “at the station” to meet them though, of course, there was no station, only the old blockhouse above the river and a rondavel or two.

Nobody knew what a “game reserve” meant in those days. These visitors seem to have expected a vast, fenced enclosure where tame fallow deer might be expected to salute them while hungry lions roamed about outside. They were startled to find the primitive conditions under which the warden lived and even more startled to find that bully beef was almost all there was to eat (Stevenson-Hamilton’s cook improved the shining hour by serving a curry made with Cooper’s Dip which the host snatched from beneath the noses of his guests in the nick of time).

What happened after that is best told in the warden’s own words.

“It was, perhaps, a little disconcerting when one had been practising self-denial in the midst of comparative plenty to find people, and officials connected with game preservation at that, fresh from a hearty beef and mutton diet, crying out for game meat, and to hear one of them ejaculate as an impala ewe, inspire with newly engendered confidence, stood gazing at him within fifty yards distance, ‘Oh, what a lovely shot; how I wish I had my gun’.

“Great surprise and some incredulity was evinced when I confessed I never shot any game and I was told I ‘ought to keep my eye in’. Indeed it was not long before I received what amounted to an order to go and slay a buck for my guests. With assumed cheerfulness I fared forth accordingly. Presently, having returned and made confession that I had been so unfortunate as to miss the only animal seen, a deep gloom settled on the party which was maintained until by a happy inspiration a member of it, reputed to be a good shot, volunteered to see if he could do better than the discredited warden.

“I lent him my rifle and in due course guided him to within range of a herd of impala when, rather to my relief, the expert made two clean misses and the animals disappeared into the blue. In justice to him I ought to add that I had stupidly forgotten to tell him that the rifle shot high.”

Even his immediate superiors in the Milner administration had failed to grasp his ideas. They, too, thought that a game reserve was really nothing more than a preserve for privileged people.

Later on Sir Godfrey Lagden, who had been a most sympathetic and helpful chief, made a remark that must have cut him to the quick.

“Hamilton, what a good thing it was that I didn’t appoint a sportsman to your job!” he said.

Stevenson-Hamilton commented drily: “No doubt the term is capable of different interpretations.”

That was the game reserve’s first visit from its departmental head – and its last for twenty years. In 1923 Colonel Deneys Reitz, Minister of Lands under whose departmental control the reserve was to fall, paid it a visit and was deeply impressed by all he saw, but in the intervening years not one of the number of administrators whose financial charge it was thought it worth going there. From time to time minor officials went there because they had to, and in 1916 the members of the Game Reserve Commission decided that an inspection in loco was necessary. But for the rest of the time, Stevenson-Hamilton was left severely alone. This is in marked contrast to what happens today when not a month goes by without some sort of official visit and most members of the Cabinet find time to “look in”. Of course, communications were much more difficult then than they are today and there was the danger of contracting malaria. But the fact remains that not one of the men who spoke so eloquently in favour of abolishing the reserve or of handing it over to the farmers, had ever been there.

A member of the Legislative Council of the Transvaal once rose in that assembly to attack the preservation of wild animals and to criticise the “extravagant salaries” paid to the warden and the rangers. “Why,” he declared, “I would do it myself without any pay at all – just for the shooting.” Needless to say he had never been there.

Stevenson-Hamilton did not mind this loneliness. In fact, as time went by, he grew to like it. He was the lone hand. Except when he arrived in Pretoria to ask for more money for more staff or more regulations, nobody gave a damn as to what he was doing. He was the captain of his ship, the sole policy-maker and the laird of 14,000 square miles of wild country. And already the game was coming back to its old haunts. There were more impala, more buffalo, more lions. Within two years his policy had begun to show results – and South Africa had tightened her embrace. DM

Eden Lost, and Regained by AP Cartwright, with a foreword by Tim Cartwright, is published by Footprint Press.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider