BOOK EXTRACT

8000 Days: Ambush in the office

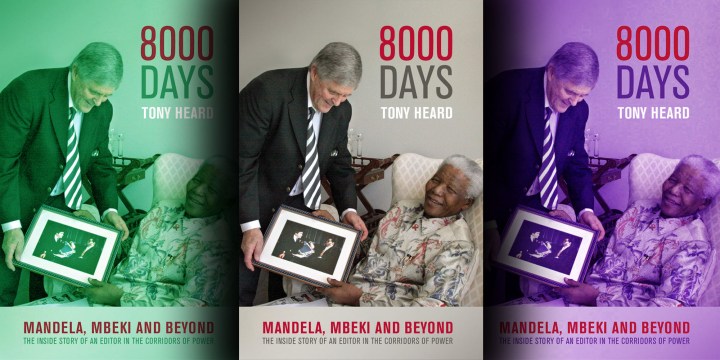

In his new book, ‘8000 Days’, former Cape Times editor Tony Heard describes his decade in the Presidency as special adviser, and a dozen years elsewhere in government. He interacts with Presidents Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki, and joins their entourages on two unforgettable visits to the UK. In this extract, Heard describes a remarkable ambush in his office by the eccentric ex-Minister of Health, Manto Tshabalala-Msimang.

She bore down on me with a vengeance showing unshakeable belief in a myth of the age.

It was spring 2008. The scene was the Union Buildings in Pretoria, in my office in the West Wing.

The issue was HIV/Aids.

Her name was Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, who was married to influential Mendi Msimang, former treasurer-general of the ANC.

This visit meant trouble.

There was a caretaker president in office in South Africa, Kgalema Motlanthe, who had previously been minister without portfolio in the Presidency. His career had been more than upwardly mobile.

The president-in-waiting, Jacob Zuma, licking victorious lips, was preparing for what the astute commentator, Max du Preez, was to describe as his “wrecking-ball” role in the nation.

A lesser question had nagged us in the Presidency: who would succeed Motlanthe as the new minister in the Presidency? The choice was Motlanthe’s, as interim president, working with the ruling ANC headquarters (HQ) in Johannesburg.

Those of us serving in an already shell-shocked place because of the removal of President Mbeki did not have long to wait. High farce lay ahead for me.

Tshabalala-Msimang, a former controversial health minister, was soon stalking the corridors of the Union Buildings titled “minister in the Presidency”. We who worked on the second floor would see her each day, walking from the lift to the large corner office once occupied by previous incumbent Dr Essop Pahad. This was a space I knew well. I would view her guardedly as she passed my door. I was no fan. I saw only awkwardness ahead.

I had been special adviser to Pahad but, in 2004, had branched out to an advisory job working right across the Presidency, not only for the minister. That arrangement, serving several Principals and not one, had suited me well.

One day, Manto had made an unexpected appearance in the Presidency after having been removed from the health ministry, where she had caused such damage in her stewardship of HIV/Aids under Mbeki.

Not knowing the subtleties of my job title, some friends, including presidential wordsmith Ken Gardner, had mirthfully texted me condolences, assuming I’d inherited Manto as my minister. They knew I’d prefer eating glass.

With glumness, I saw my record of 14 years advising in Presidency and government ending in ignominy, as I was assumed to be serving someone for whom I had no respect. That would have meant my resignation.

It is a state many threatened civil servants and politicians know, the sudden career slide-down. I had tasted some splendid moments working as adviser or as drafter and speechwriter for figures I respected and liked in the Presidency, especially with President Thabo Mbeki in overall charge, his own fall having led to Motlanthe’s rise.

I loathed the thought of working, even remotely, for this eccentric ex-health minister. She had, more than any other, helped tarnish Mbeki’s reputation, and South Africa’s. In those early years of the new millennium, our country had been in the eye of a global storm when our government under Mbeki was perceived as dissidently questioning the firmly established link between HIV and Aids (in medical terms, Aids being a life-threatening, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, caused by the virus, HIV).

I had thought the debate around Mbeki’s position on Aids was not only lost, but over, with the more mainstream Motlanthe in charge in South Africa. I was to be surprised in more ways than one.

Suddenly, shortly after her appointment, there was an unannounced visit from Manto to my own office.

Right in front of me stood a bugbear figure – for me and most of South Africa.

She came straight in, led by competent, agreeable Caroline Mangwane, who had deserved her promotion to administrative secretary in the ministry.

At first sight, this could have been mistaken for a goodwill visit by Manto, to meet and greet those whom she, as minister in the Presidency, would see as her own staff situated on the second floor. The thought gave me no comfort.

She seemed relaxed to begin with. She spoke to me as if I were one of the advisers dedicated to her new job. This required nifty footwork, denial and explanation, which I did with a vehemence born of nervousness. No, I averred, I had left the ministry in the Presidency, and my post fell under the director general, on the budget of communications in the Presidency. That is, I was at one remove from the ministry she had inherited.

After some confusion, Manto twigged. I was not part of her own dedicated staff but instead served the Presidency in general.

While this sank in, and after reflection on both sides, with the drone of Pretoria and the random hooting of Church Street taxis below, we settled on a tolerable way forward. She asked me whether I could help any of her staff who lacked experience in their new jobs. That was fine, I said, relieved to see a way forward.

Then her soft voice suddenly changed from relaxed to hostile, with a certain shrillness.

She abruptly thrust her diminutive frame forward, in front of Caroline Mangwane. The minister looked relatively healthy, though weakened after a liver transplant, following which she had done widely publicised jumping-jack exercises outside Parliament. I felt cornered, as she launched an obviously prepared attack:

“It was people like Joel (Netshitenzhe, presidential policy guru) and you who were so wrong to try to get President Mbeki not to speak on Aids.”

I was flabbergasted. There was a hint of an incongruous smile on her face which made the moment seem more bizarre. For me, it was incredible to discover that the discredited Aids-denial was still her stock-in-trade.

Here was a senior minister, marching into my office (behaviour unusual for ministers), to give me a lecture on my and others’ attitudes over a botched Aids policy. It had of course been sensibly well-revised by then (2008) through the combined forces of public opinion, NGOs, the courts, and cabinet pressure. The chief ruminator on Aids, Mbeki, was out of office anyway.

Stunned, I held my ground, asserting that those who had tried to keep President Mbeki quiet on Aids had done so out of a sense of patriotism and concern for his rightful place in history. It was designed to keep him and our country out of trouble, which was our main job as presidential advisers. I was puzzled that she bracketed me with Joel, who had played a much more significant role than I had in fighting inside government what was viewed as Mbeki’s denialism over Aids.

Standing my ground against a minister, I thought this was the firing moment. Dismissal is a distinction I have known only twice in my career: as the editor of the Cape Times in 1987 and with most of George Soros’s Open Society Foundation for South Africa board in the mid-1990s when the US philanthropist felt, inter alia, that too many of us (three in number) worked for the Presidency.

Firing by Manto Tshabalala-Msimang would mark a hat-trick of distinguished dismissals.

Though not technically my minister, she could have arranged my rapid departure in her new position. Firings by then were passé in the Presidency with Mbeki camp followers either having left or leaving that once so inviting apex of government.

My remark drew a retort from Manto that made me realise how far her judgement had deserted her in the Aids fiasco.

She said: “… and now you can see, Mr Heard, from what is happening in the world over Aids, how right we have been proved to be all along. The whole world now accepts the approach we adopted.” She meant, of course, the dissident views she had held to so disastrously as health minister. All I could think was, this is incredible.

She could not have been more wrong. She had always sought to conflate nutrition with cure. She seemed to think that reliance on her favourite onions, beetroot, garlic, olive oil, potato or lemon, and God knows what else, had finally won through as Aids cures in the view of a contrite world once over-reliant on antiretrovirals.

She was blind to the dark days of public confusion and ridicule we had endured, especially in the Presidency. She was also blind to the savaging Mbeki still received on this issue, even after his political fall, not to mention the countless tragic deaths we continued to experience in South Africa.

She did not seem to appreciate how far, under President Motlanthe, we were moving in the right direction on Aids. Nor how universally the medical world had applauded us over this paradigm shift and the roll-out of antiretroviral drugs, our distribution to become the highest per capita globally.

The exchange confirmed what I’d felt for years. The satirists and cartoonists had been dead right to depict Manto as worse than eccentric. In that conversation she failed to betray the slightest notion that she might be wrong. I was reminded of Dr Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd’s omniscient self-confidence that I’d seen decades ago in Parliament, as he brought us to the brink of ruin.

The encounter on the second floor ended inconclusively, but I still value the measure of vindication I felt. More senior and influential officials than I, notably the hero of the piece, Joel Netshitenzhe, had fought that corner in a Presidency once seen as a global laughing stock on the issue.

I felt personally delivered from at least some of the opprobrium heaped on us down the years. My vindication was qualified by the thought that we, those around Mbeki, should have been tougher in resisting his public ruminations.

That was the last time I saw Manto. In the next few months before the elections of 2009 I avoided her in exemplary public service ducking and weaving, facilitated by the labyrinthine nature of the Union Buildings, and my lengthy stays in Cape Town for my work. Manto was based mostly in Pretoria till her merciful fall from Cabinet when President Zuma took over in mid-2009, as we unknowingly faced more woes.

Despite Manto’s obstinacy and her strictures aimed at me, I was saddened to note her death in December 2009. Not to mourn the departed, with few exceptions, reduces one’s own humanity. An eye-opener was the praise heaped on her by ANC heavyweights at the funeral. Many who had privately or publicly disagreed with her on Aids joined in the tribute to her life of struggle. In her day, she had been part of a great movement seeking elementary justice in our land. She will be remembered for the idiocy over Aids.

How, then, did I – a newspaperman for 40 years – transmogrify to the Presidency for a decade, and to government departments for a dozen years? In all, this covered 22 of our first 25 years as a democracy, in other words, 8,000 days. DM

Tony Heard is a former editor of the Cape Times, and spent a decade in the South African Presidency as special adviser, and a dozen years elsewhere in government. He has a philosophy honours degree from the University of Cape Town, and as editor of the Cape Times, was awarded the international Golden Pen of Freedom in 1985. He is the author of The Cape of Storms, and was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard University. 8000 Days is co-published with Missing Ink.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider