South Africa

Needle and thread rebellions for a broken world

‘Has the pen or the pencil dipped so deep in the blood of the human race as the needle?’ Olive Schreiner once asked. Maverick Citizen examines the revival of the so-called feminine arts as acts of radical engagement in world problems.

At a recent exhibition of work by young artist-activists, Sydney Adams, who calls herself an “art-school drop-out”, sewed blank cotton dolls in diverse flesh-like colours. Participants in this art intervention were invited to stuff tissues, wet wipes, bandages, tea bags and dried lavender into the openings Adams had closed up with zips. “The stuffing of the dolls is two things: violation by another on the one hand, and healing by the self on the other. People get to think about what women hold, what they carry.” The installation was called Build-A-Woman. (Photo: Karin Schimke)

A few years ago, a young man was visiting Willemien de Villiers’ Muizenburg studio. He was gazing at the images pegged up on a kind of washing line on the wall while De Villiers chatted to his mother.

“I saw him peer more closely at one of the pictures and then I saw him recoil. He actually jerked back.”

De Villiers looks out on to a little courtyard, the French doors are open and lengths of embroidered linen shiver and flap in the breeze. The walls are a minty green. On an easel is an unfinished painting in black, red and pink of a woman as you would find her depicted in medical texts. There’s a weaving frame on the table with half-finished cloth on it, and directly in front of her chair is a delicate mess of mostly pink and red threads, threaded needles, pins in pincushions, scissors, and stained and ruined second-hand tray cloths.

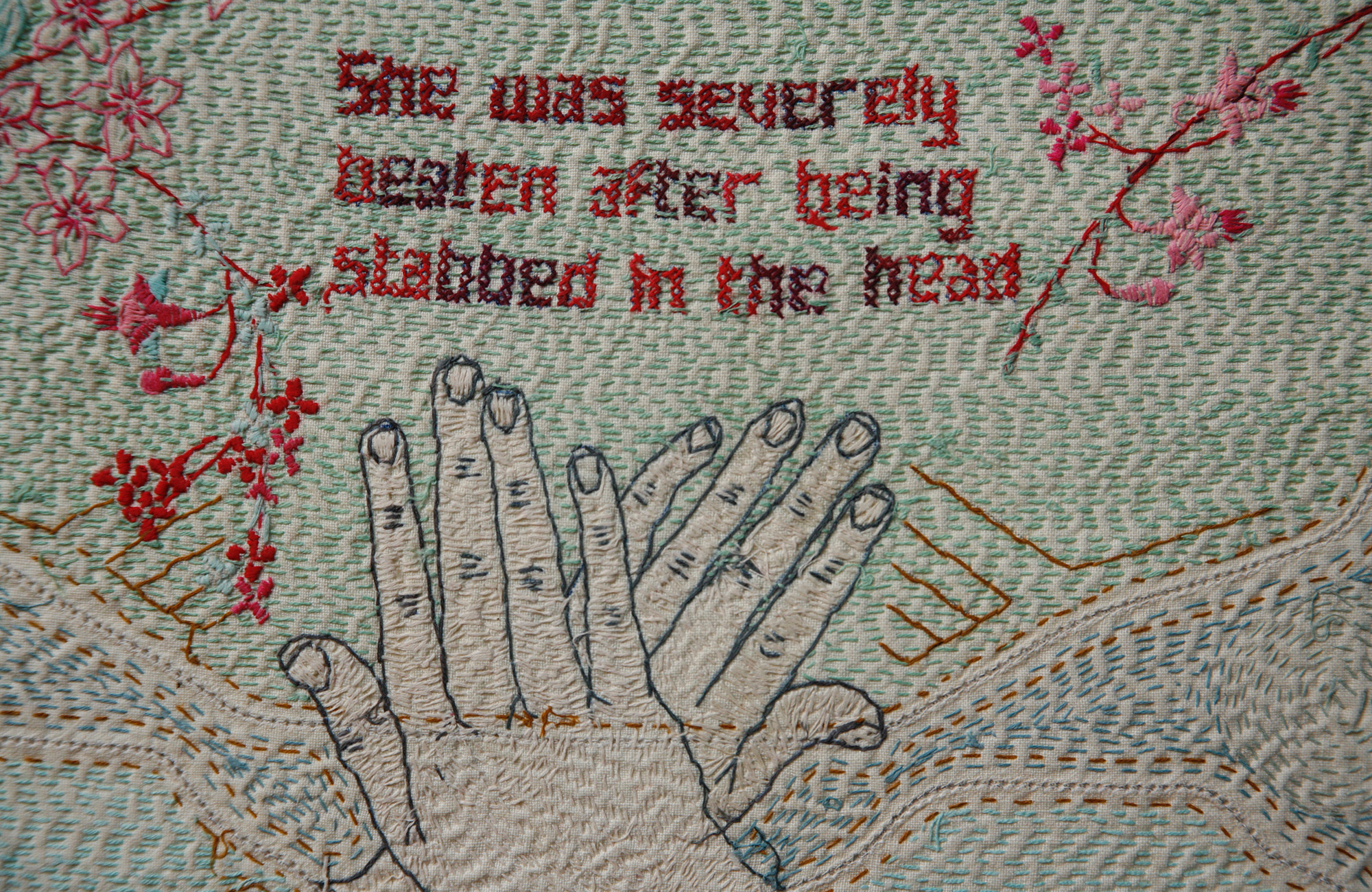

What the young man had reeled back from in the midst of all this unthreatening femininity was a photograph of an embroidered panel: the delicate depiction of a pair of hands resting on top of one another in a restful, almost resigned, way, with red flowers tumbling down the margins.

Above the hands, cross-stitched in various shades of red, from fresh blood to clotted wound, are the words: “She was severely beaten after being stabbed in the head.”

A detail from a panel of work that is part of a series called “Domestic”, which De Villiers stitched in response to words found in newspaper reports on domestic violence. (Photo: Willemien de Villiers)

Mary Sibanda is an internationally acclaimed South African artist, probably best known for her work Long Live The Dead Queen, in which fabric plays such a significant part of the story she is telling. In it, her alter-ego, Sophie – a domestic worker – is represented as a life-sized closed-eyed figure kitted out in voluminous Victorian-style dresses which, in colour and finishing, are reminiscent of the ubiquitous South African domestic worker uniform with its fringed half-apron. Sophie’s eyes are always closed against her reality – servitude – while she dreams herself into the realms of the coloniser, the powerful.

“To know the history of embroidery is to know the history of women,” says Rozsika Parker, author of The Subversive Stitch.

Women producing things using needles and thread is a story as long as the history of humans. Some, like Sibanda and De Villiers use fabric as an extension of that history to produce internationally acclaimed art. They make visible what has, for the most part, been consigned to the private women’s world of domesticity and servitude.

De Villiers embroidered this image from a vintage life-saving manual on the back of a tray cloth. “I suspect it was an antidote to the despair I felt making the “Domestic” series, which was based on actual newspaper reports on incidents of gender-based violence. I felt drawn to the gentleness of these imagines. They reconnected me to the basic goodness of human beings, the possibility of kinder connections.” (Photo: Willemien de Villiers)

Textiles were one of the world’s first major industries, but with industrialisation, production was shifted to factories where men were used as spinners to work the machines. The result of this was “the dispersion, deauthorisation, and expropriation of women’s skills and knowledges along with the destruction of many women’s bodies (the witch burning). The rest of these knowledges and practices were consigned to the domestic sphere as ‘mere’ reproduction,” write Jack Z Bratich and Heidi M Brush in an article entitle “Fabricating Activism: Craft-Work, Popular Culture and Gender” in a scholarly magazine called Utopian Studies.

The word “craft”, which is employed to cover the knitting, crochet, embroidery, tapestry, weaving and sewing, and which has in recent years spawned a pop culture wave of hipster handiwork all over the interwebs, is telling because of its associations with trickery.

To be “crafty” is to be clever and sly in order to achieve your aims by indirect or even deceitful means.

Like Philomela, a minor character in Greek mythology, did. She used tapestry to communicate her rape and the cutting out of her tongue by her rapist. When her message was received, her violation was spectacularly avenged.

Madame Defarge, the fictional “bitter-knitter” from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, knits the names of aristocrats to be sent to the guillotine into her work.

In a more recent act of fabric rebellion, unpaid factory workers in Turkey sewed hidden notes into Zara clothing, saying things like, “I made this item you’re going to buy, but I didn’t get paid for it.”

The rise of social media seems to have ushered in a new era of interest in what has always been considered the hidden labour of the domestic arts. Fabric craft is perfectly suited for cocking a snook at power because it resists being integrated into profit-making systems. It is slow, not fast. It is personal and experiential rather than repetitive and specialised. It encourages a gift exchange instead of supporting mass production. It is communal, even while it is individual. The softness of its materials stands in contrast with the rigidity of war paraphernalia. It exalts value over convenience, and production over consumption.

What was always pushed to the margins, limited to the confines of the home and labelled “women’s work”, is now a world-wide trend that revels in its anti-capitalist, anti-war, pro-environmental and pro-social justice stance.

De Villiers is drawn to pictures from old medical texts. Her embroidery is saturated with this kind of imagery, and the reproductive parts of plants and humans are almost always in evidence in some form or another, blurring the boundaries between species and pointing to the interconnectedness of all life. (Photo: Willemien de Villiers)

The interior has been made exterior. Crafts have come out of the closet. Seeing them practised in public realms is experienced as extremely unsettling, just as breastfeeding in public was — often still is — seen as obscene.

Sue Montgomery, a mayor in Canada, made the news in May 2019 because she knits during council meetings. What really upset people, was not so much that she was knitting — though doing so in meetings is thought to be disrespectful, while knitters say it helps them concentrate better — but how she was knitting. She knitted in red when men spoke and in green when women spoke. The product is a garment that is overwhelmingly red. She said she realised her work was a generalisation, but she found that women were succinct in their addresses, while men were far more inclined to pontificate and seemed to like to hear themselves talk. The knitting bears that out.

Revealing what was once hidden is in itself a powerful statement. One of its consequences is that it has dented formerly inflexible ideas about gender. Social media is awash with hashtags like #menwhoknit and #manbroiderer. While the use of soft materials contrasts strongly with hyper-masculinity, fabric work is no longer seen as only women’s work.

From artists like Abdoulaye Konaté and Pierre Fouché, to the men and boys who sew, knit, crochet and embroider for their own pleasure, textile arts and craft are no longer seen as an exclusively female undertaking, and so a new layer has been added to what is often called “craftivism”.

“Craftivism” is a term coined by the author Betty Greer in 2003 for work that combines craft and activism, according to the book The Subversive Stitch, by Rozsika Parker.

“Craftivism is a way of looking at life where voicing opinions through creativity makes your voice stronger,, your compassion deeper and your quest for justice more infinite,” Greer is reported as having said.

Some feminists have criticised the rise of female handiwork in the public realm, saying it is more retrograde than it is radical, enforcing the ideas of women’s work. These critics do not appear to be in the majority. Other feminist thinkers say that the renewed interest in what falls under the domestic arts reclaims and revalues the activities of women. The old domesticity was associated with female subordination, restricted social roles and gendered labour divisions, while the products of their labours were devalued. This new domesticity is the middle finger to all of those things.

While fabric crafts have become more public, some things about fabric art have never changed: it has always been a source of community, creative satisfaction, relaxation and concentration.

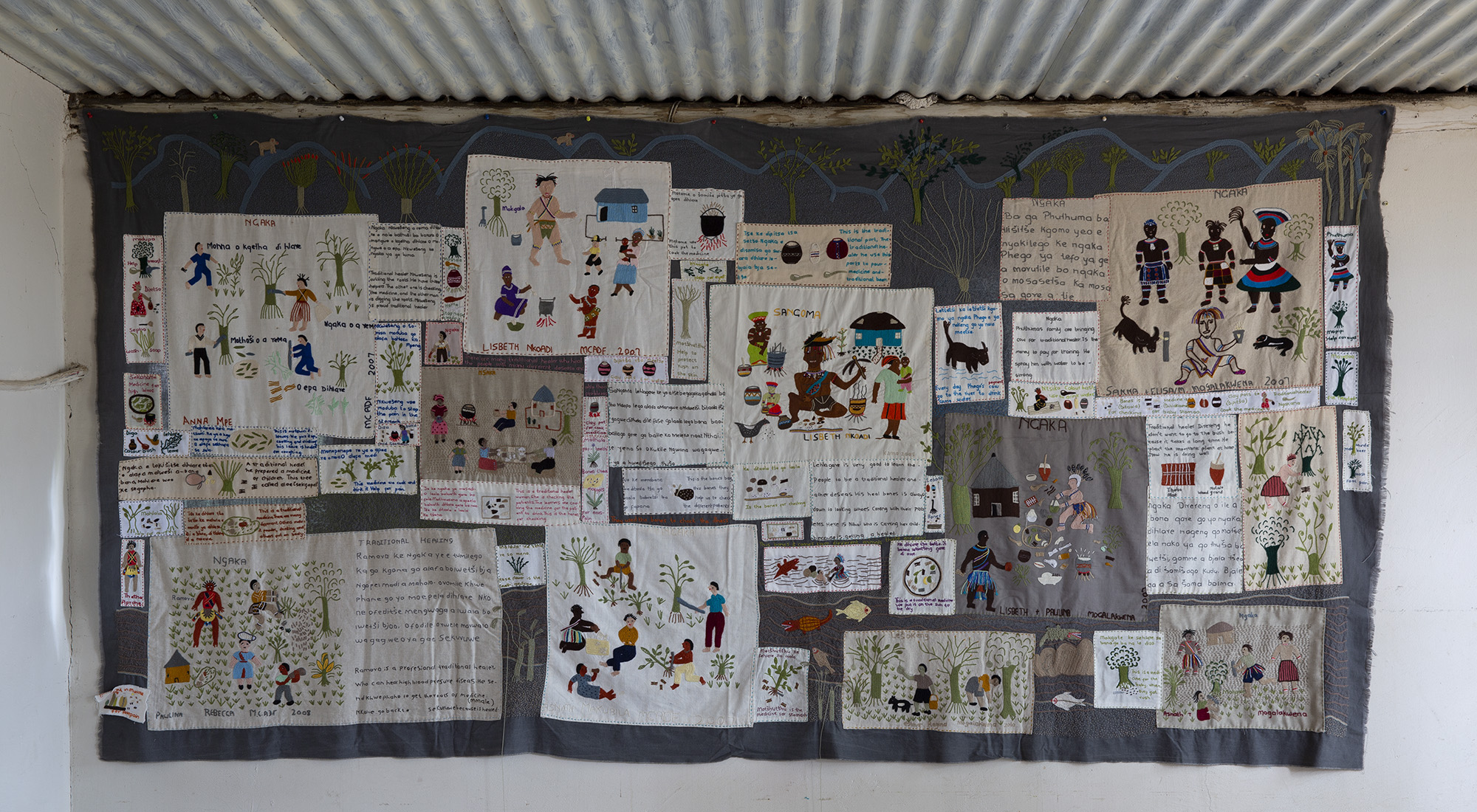

In order to communicate their traditional knowledge across language barriers, the women of the remote northern Limpopo began to draw and then embroider cloth panels in answer to questions about their way of life from researcher Elbé Coetsee. The embroidered pictures are painstakingly recorded in writing by two or three of the craft artists with basic Sepedi literacy skills, and then the text is embroidered too. The text is translated into English and then also embroidered. Embroidery here is used as a means of documenting an oral culture. (Photo: Elbé Coetsee)

The British Journal of Occupational Therapy reported in 2013 that “knitting has significant psychological and social benefits, which can contribute to well-being and quality of life”. The results of a study showed “a significant relationship between knitting frequency and feeling calm and happy”.

This, no doubt, was discovered by the political prisoners on Robben Island who learnt to knit from the MK cadre JJ Maake, who in turn learned the skill from an old woman who gave him sanctuary from the apartheid police. Maake’s contribution to life on the prison island is documented in a book called The Lighter Side of Robben Island.

The journal article reported that “knitting in a group impacted significantly on perceived happiness, improved social contact and communication with others”.

Geli Ngcobo lives in an old-age home for women with limited means in downtown Johannesburg. She belongs to a small group of women who knit for The Seen Collective, which uses hand-spun, hand-dyed yarn from the Eastern Cape.

“I’ve been sewing for years, now I knit. I used to make therapy teddies for the police to give to abused children. I like making garments more than toys. I enjoyed it so much when I saw someone wearing one of our pieces… something I’d made with my own hands! And I like coming to our meetings, talking and being together.”

Her colleague Averil Erasmus says she’s never crafted in a group setting before but really looks forward to the weekly meetings. Each woman is paid per piece of work she completes. The project was started by Steph Mundy who wanted, among other things, to get “the incredible crafting skills” of these women seen.

There are craft groups everywhere — online and in real life — and they exist for the combination of the pleasure of community as well as the satisfaction of production.

One professional woman, who preferred not to be named and who has been part of a sewing and knitting group for years, says: “We boost one another, we inspire one another… the group gives us a chance to connect again in our busy lives. And they have such interesting things to share because of their careers. One woman is a paediatric anaesthetist, for instance, and another is a documentary film maker who is currently work on a doccie about land occupation.”

Helen Brain, an internationally published author and creative writing tutor, began to make washable pads when she read about women at Mowbray Maternity Hospital who couldn’t afford to buy pads and the hospital doesn’t supply them.

“I began making them, and then invited anyone to join me via my Facebook friends.”

The group has met once a month since the beginning of 2019 and the women make about 20 washable pads per session. They’ve begun crowdfunding for supplies and members “ferret out” old towels and flannel sheets that they upcycle. Not all the women who come can sew, but people trace patterns, cut, fold and iron.

“What I love about the group is the way everyone’s strengths pull together. We have good organisers, people who are good spatially, people who like working out processes for improving. We have a couple of amazing sewers who churn through the stitching month after month.”

Brain has always worked with her hands. She has attention deficit disorder and can’t sit still.

“If kids learned to do crafty stuff, there’d be less occupational therapy necessary, I’m certain of it. We sometimes have children come to our meetings, and I love the sense of community, of strong women coming together with a mutual goal. And it’s important for kids to see this in action.”

Knitting and sewing are thought to have significant social and psychological benefits that contribute to well-being and quality of life.

Working with fabric, in whatever way, to produce something useful or beautiful is thought to be therapeutic. And, whether it’s done publicly, privately, politically or for pleasure, this new, intense, out-and-proud period of re-engagement with the so-called feminine arts may, in future, be seen as the contextual moment of the #metoo movement.

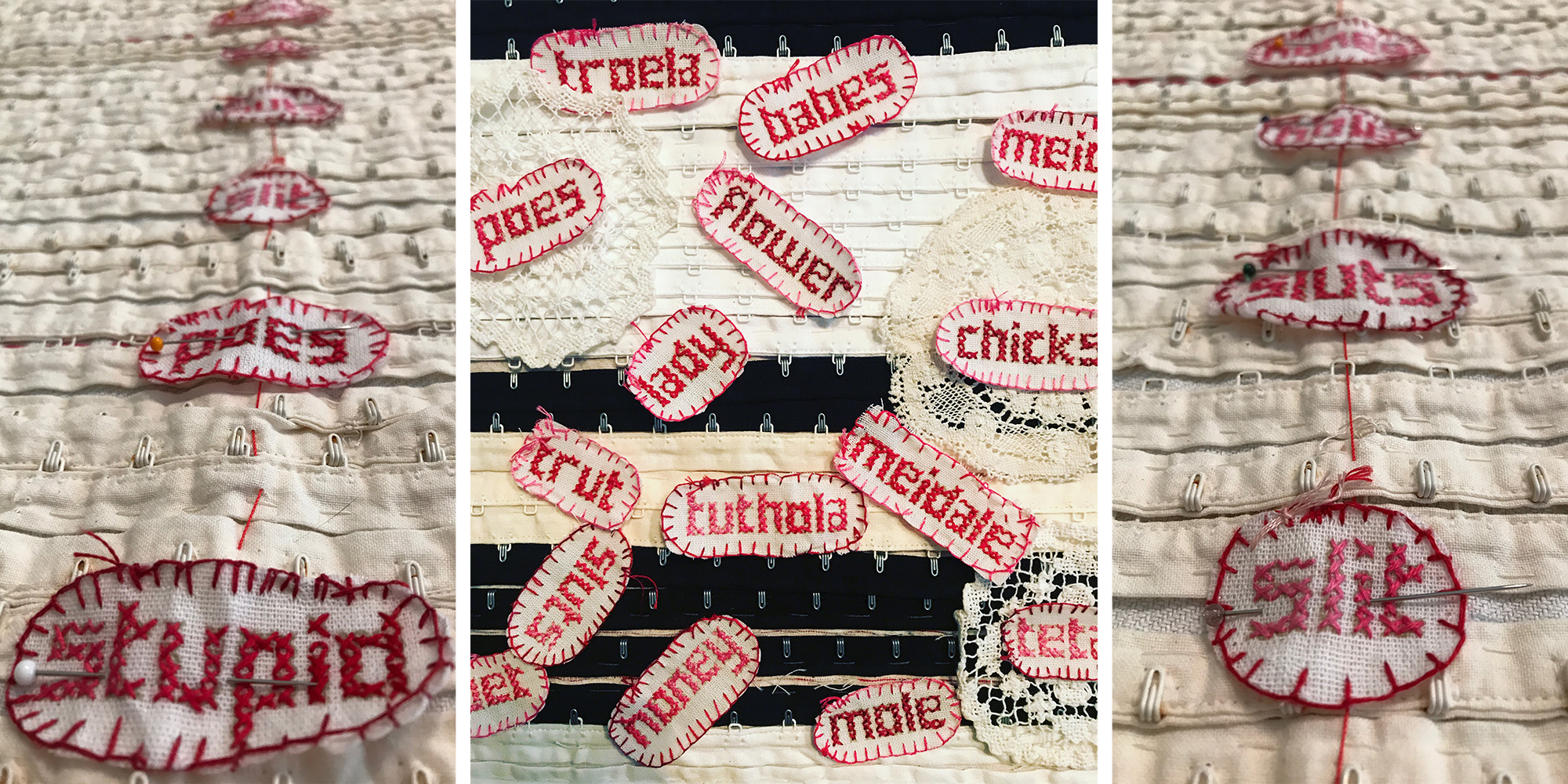

De Villiers, who has a large international following on Instagram, asked her followers to send her words used to describe women and girls while they were growing up. The words could be in any language. The responses have become part of an ongoing series in which the artist cross-stitches the words and then combines them with haberdashery ‘notions’ like hooks and eyes, bra fasteners, and other bits and bobs used specifically in female undergarment construction. (Photo: Willemien de Villiers)

De Villiers sweeps two flat hands out across a second-hand tea towel lying in front of her. She tips the last of her coffee, sludgey with the finest grounds that have sifted to the bottom of the cup, over the fabric and then scrunches the whole thing up. Pristine cloth is not for her. The staining is an effort to work in against the pervasive tropes of females of purity, chastity, vulnerability and delicacy. She often works on the reverse sides of second-hand linens found in charity shops and which have been stitched by women whose names she will never know. She works around holes and tears and stains, rendering each piece something that has an unknowable “back story” and confrontational “front story”.

“These endless rituals of cleaning, of ‘making nice’ that have always fallen to women…” she trails off as she flattens out the newly dirtied cloth again. “I find it liberating to stain things.” MC

For more information on the Limpopo research project on rendering oral knowledge in embroidered panels http://www.mogalakwena.com/index.html

Become an Insider

Become an Insider