GRAND THEFT, OR TWO

How the Greeks lost their Marbles: Britain’s shameful colonial loot

There is very little that is British in the British Museum, the joke goes, it was all stolen from other countries. Now, as calls grow for the museum to give back the priceless objects looted during the colonial wars, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, a new book by a leading international human rights lawyer makes the case for the return of its greatest treasure — the Parthenon Marbles.

“When I hear the word ‘culture’, I reach for my gun.” That line, originating from a 1933 play honouring Adolf Hitler, is often misattributed to Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and suggests the Führer’s deputy may have been a bit of a Philistine. Far from it. Such was his appreciation of culture that his firearm was almost certainly drawn when he came across a work of art — in order to steal it. The British, of course, did much the same in their colonial wars.

Sections of the Parthenon Marbles, also known as the Elgin Marbles. (Photo: Dan Kitwood / Getty Images)

Göring profited from one of the greatest organised art thefts in history. The Nazis freely looted European museums, libraries and private collections, mostly Jewish. Some 26,000 railway cars full of paintings, sculptures and other stolen items were sent to Germany from France alone. Göring helped himself to the best. As he later explained at Nuremberg, “during a war everybody loots a little bit.”

On November 18 2019, one of the more than 1,500 stolen pieces in his collection, a 6th century BC Grecian wine chalice, went on display in an Athens museum after being “lost” for some 80 years. It was reportedly smuggled out of the country in a diplomatic pouch by Göring when he visited Greece in 1934. It was finally traced to the University of Münster in 2014 and duly returned.

Plaques that form part of the Benin Bronzes on display at The British Museum. (Photo: Dan Kitwood / Getty Images)

The return of this Raubkunst, as the Germans have dubbed Nazi loot, is but one small victory in Greece’s long, ongoing campaign to recover its cultural heritage. The return, however, of the greatest of all its plundered art, the Parthenon Marbles (also known as the Elgin Marbles), continues to elude them.

These are the sculptures of gods, men and horses created some 2,500 years ago that were an integral part of the temple of the Parthenon and other buildings of the Acropolis of Athens. The Parthenon itself is one of the most important edifices in all of history. Built in 447BC after the Greeks had successfully repulsed Persian invaders, it symbolised the blossoming of democracy, rule of law, philosophy, ethics, theatre, art and architecture in Western civilisation.

Greece had been occupied by several invading nations over the centuries, but it is only Britain that stands accused of directly attacking and vandalising the Parthenon: a British diplomat, Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, directed workers to hack away about half the friezes from the upper walls of the temple and surrounding buildings in an act of desecration that lasted from 1801 to 1812, and then transported them by sea back to Britain.

Two centuries later and despite global pressure, Britain still refuses to return them. This intransigence was best expressed by Margaret Thatcher. When then Greek culture minister, the actress Melina Mercouri, celebrated for her role in the 1960 film Never On Sunday, called for the return of the Marbles in 1982, the UK prime minister responded, “Never on any day.”

Lord Elgin, by most accounts, was even more dislikable, a philanderer so racked by syphilis that his nose eventually fell off. He was ambassador in Constantinople (now Istanbul) when Greece was ruled by the Ottomans and had despatched a functionary to bribe the local governor in Athens and convince him that Elgin had the Ottomans’ blessing for the theft.

The heist cost Elgin around £70,000, or about £5-million in today’s terms. He’d originally wanted the Marbles to decorate Broomhall House, his home in Scotland, but a costly divorce put paid to that, and he was forced to sell them to the British government to settle his debts. The Marbles were then handed over to the British Museum, where they have been ever since.

The museum’s directors and successive Westminster governments have long maintained Elgin had been in possession of an official document — a firman granted by the Ottomans — that entitled him to remove the Marbles. No-one has yet located a copy of this document, either in Ottoman archives or in Elgin’s papers.

This is one of many questionable aspects surrounding the Marbles that is tackled by the QC and international human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson in a new book, Who Owns History?: Elgin’s Loot and the Case for Returning Plundered Treasure (Biteback Publishing), that challenges every statement and lie told by Elgin and the ongoing official state justification of his looting.

Robertson argues there was no firman. What Elgin had instead was permission to measure and make moulds of the Marbles — not rip them off the walls and take them home.

But Robertson is concerned with more than the Marbles; his book, he writes, is “about how people can lose or misunderstand the heritage of their own country when it is kept under lock and key” in institutions that have been described as “museums of blood”.

“Yet,” he adds, “remedy for loss is unavailable today: mighty ‘encyclopaedic’ museums like the Met and the British Museum and the V&A and the Louvre and the Getty and soon the Humboldt Forum lock up the precious legacy of other lands, taken from their people by wars of aggression, theft and duplicity, and there is no forum to which they can turn to get them back, at least if they were wrongfully obtained before 1970, the date of Unesco’s first and only convention on the subject.

“This means the most valuable treasures of antiquity are withheld from the people whose ancestors created them and which could inspire their youth anew with the story they tell and the knowledge that their progenitors could once create such beauty.”

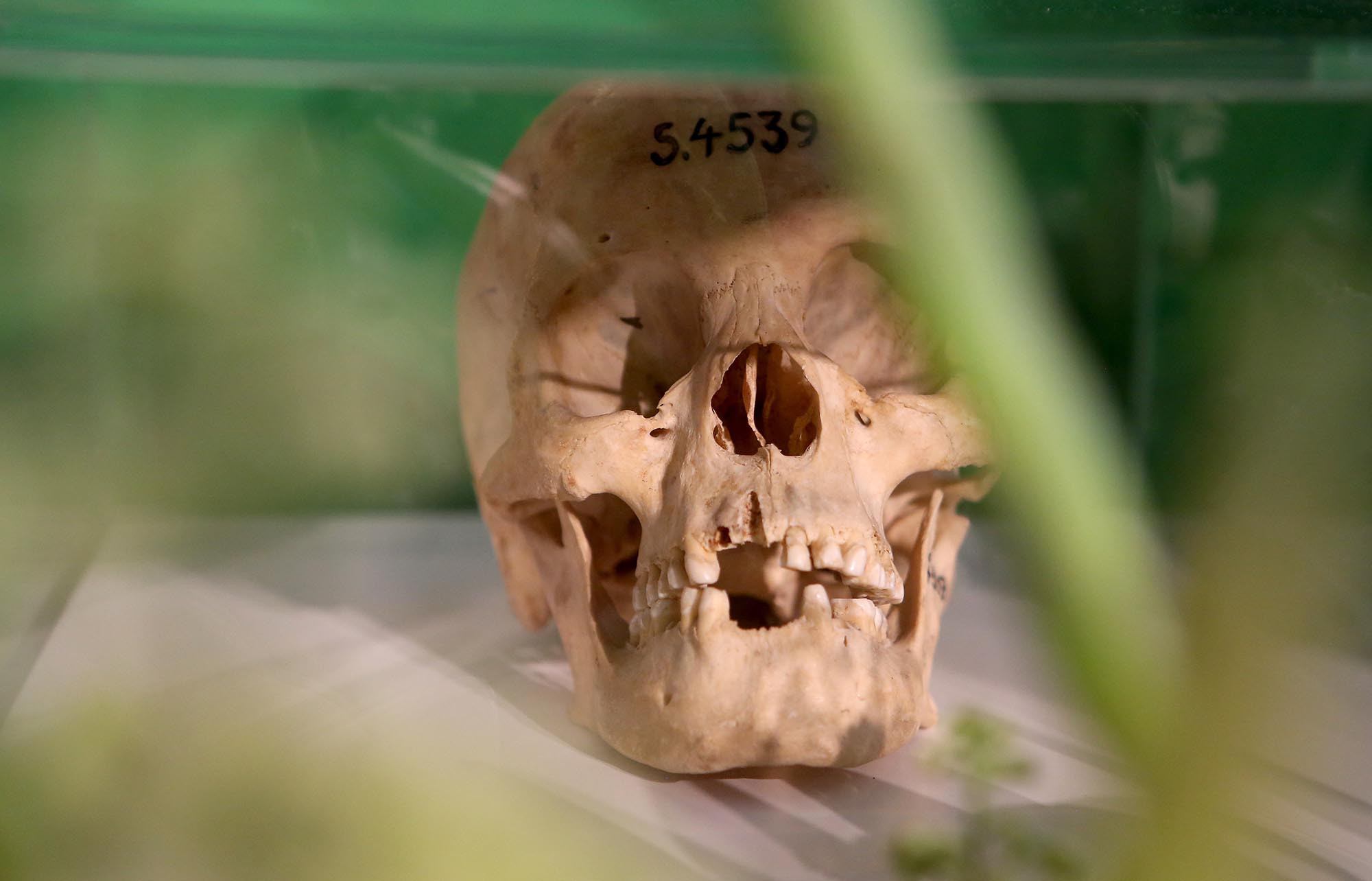

Robertson was approached by the Greek government in 2011 to investigate whether international human rights law could help in retrieving the Marbles. At the time, he’d just won a celebrated precedent-setting action compelling the Natural History Museum in London to repatriate the remains of Aboriginals stolen by grave-robbing British troops in Tasmania in the 19th century.

Sarah Baartman. (Archive image: www.up.ac.za)

“The case for repatriation of human remains from museums is now widely accepted,” he writes, “whether or not the death came as a result of colonial oppression. France returned to South Africa the remains of Sarah Baartman, who had been exhibited at fun fairs in the early 19th century as ‘the Hottentot Venus’, and Germany has ceremonially returned the skulls and bones taken from Namibia in the course of the genocide it inflicted on the Herero people. In 2019, it handed over to the Australian government and tribal representations the Aboriginal remains in its museums.

A Namibian skull from the German Empire’s murderous campaign in 1904-1908 which saw the colonizers kill an estimated 60,000 Ovaherero and 10,000 Nama people after they rose up against colonial rule, considered the first genocide of the 20th century, seen during a repatriation ceremony at the Franzoesische Friedrichstadtkirche (French Cathedral) on Gendarmenmarkt on August 29, 2018 in Berlin, Germany. (Photo: Adam Berry / Getty Images)

“If skeletons demand to be repatriated, why not the objects that decorated their tombs or were intended to remain with them in the hereafter? Why not go further, and return to countries and cultures that value their past all the heritage that had wrongly been taken from them before 1970?”

Robertson’s book, essentially, is the case that he wanted Athens to pursue against the UK and the British Museum, but the “gumptionless” government of Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras set aside his advice.

However, as Robertson told guests at his recent book launch, “the way forward” is now to approach the International Court of Justice, the UN’s principal judicial organ.

The restitution debate, he added, was revved up considerably in 2017 when France’s Emmanuel Macron declared that “colonisation was a crime against humanity” and that “African cultural heritage can no longer remain a prisoner of European museums.”

Last year, for example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Joseph Kabila stepped in to the fray, calling for the return of many of the artefacts in Belgium’s refurbished Africa Museum, outside Brussels, to be housed in the new Congolese national museum in Kinshasa, which opened its doors on November 23 2019.

The Belgian museum, for years regarded as nothing more than a showcase for King Leopold’s plunder of the Congo, closed in 2013 for a €75-million restoration and “decolonisation” process. The DRC has yet to lodge an official request for the return of the artefacts there.

Macron, meanwhile, had endorsed a report by anthropologists Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics. This document boldly stated that “90% of the material cultural legacy of sub-Saharan Africa remains preserved and housed outside the African continent”.

As such, Africa’s heritage remained out of reach to Africans, the majority of whom are young and often unaware not only of the “richness and creativity” of this legacy, but even of its very existence.

Sarr and Savoy put it thus:

“To fall under the spell of an object, to be touched by it, moved emotionally by a piece of art in a museum, brought to tears of joy, to admire its forms of ingenuity, to like the artwork’s colours, to take a photo of it, to let oneself be transformed by it: all these experiences — which are also access to forms of knowledge — cannot simply be reserved to the inheritors of an asymmetrical history, to the benefactors of an excess of privilege and mobility.”

Fine words, but in the year since their report, not one of the 90,000 sub-Saharan artefacts in French museums has been returned.

But Sarr and Savoy had at least uncorked the genie. “I think that their argument, which converses all the most horrific, brutal crimes against humanity committed in the 19th century by the armies of Britain, France, Germany, Portugal and Belgium, is one that now has to be conceded,” Robertson said.

“If Macron says that the ethnological museums of France will be inspected and that which was brutally taken, stolen in war as pillage, as spoils of war, will be returned to museums in the countries of origin. And that too, it seems to me, will support the case for returning the Marbles to Greece.”

Robertson’s book touches on several other acts of notoriety. One is the sacking of Benin City and the theft of the Benin Bronzes in 1897. Bizarrely, European museums, including the British Museum, have agreed to loan some Bronzes and other looted artefacts to Nigeria’s new Royal Museum for a planned 2021 exhibition.

Another atrocity was the razing and looting in 1860 of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing at the behest of James Bruce, the 8th Earl of Elgin, who was British High Commissioner to China. “Like father, like son,” Robertson drily notes.

The establishment has, of course, struck back. Reviewing Who Owns History? for the Financial Times, a newspaper he once edited, Richard Lambert, the current chairman of the British Museum, makes the point that prosecuting counsels “are not interested in balanced arguments”, and suggests Robertson’s polemic is a “misleading combination of moral outrage, half-truths, self-promotion and jokes”.

Lambert does, however, concede that there are “highly contested objects” in the British Museum. Since 2000, he writes, there have been “half a dozen” official claims for restitution from around the world. “That,” he adds, “is not a high proportion of a collection of some eight million objects…”

A handful, then, but still the “contested objects” must stay put; the British Museum Act of 1963 bluntly states that “objects vested in the [museum’s] Trustees as part of the collection of the Museum shall not be disposed of by them”.

“But that law can simply be amended,” Robertson counters, “either by excluding the Marbles or (preferably) by giving the trustees a general discretion to de-access so they can also return, for example, the Benin Bronzes or other cultural property seized in colonial wars.”

It is worth recalling a 2005 UK High Court bid for the return of some of these “highly contested objects”. They are the drawings by Old Masters that were part of a collection looted from the home of a Czech doctor, Arthur Feldmann, by the Nazis in 1939. Both Feldmann and his wife Gisela later perished in the Holocaust.

The museum bought these drawings “in good faith” in the late 1940s without knowing any of this. The court did, but ruled that the museum’s trustees could not return the drawings, then worth an estimated £150,000. Peter Goldsmith, Britain’s Attorney General, had asked the court to determine whether the return could be permitted on the grounds of “moral obligation”.

The answer was unequivocal.“No moral obligation,” Justice Andrew Moritt said, “can justify a disposition by the Trustees of an object forming part of the collections of the museum.”

Afterwards, the museum said its trustees “do not accept” that there is a moral claim to any objects in its collection other than the Feldmann drawings.

Just four items out of eight million?

If, as Lambert suggests, Robertson has presented a case for the prosecution, the British Museum has yet to offer a credible defence. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider