Maverick Citizen: Limpopo

Villagers face daily terror of killer crocs

A trip to photocopy documents or access basic government services could lead to death or the loss of a limb for villagers in Limpopo.

A man crosses the Olifants River from Mogalatjane Elandskraal in Limpopo. Several people have been attacked by crocodiles while crossing the river. Photo: Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media

Talane Leshaba thought he was going to die when he found himself trapped in the jaws of a crocodile. He was swimming across the Olifants River, heading home to Mogalatjane village from Elandskraal, when the reptile pounced.

Leshaba lives in Mogalatjane, one of several Limpopo villages on the banks of the Olifants, the river known to locals as Lepelle.

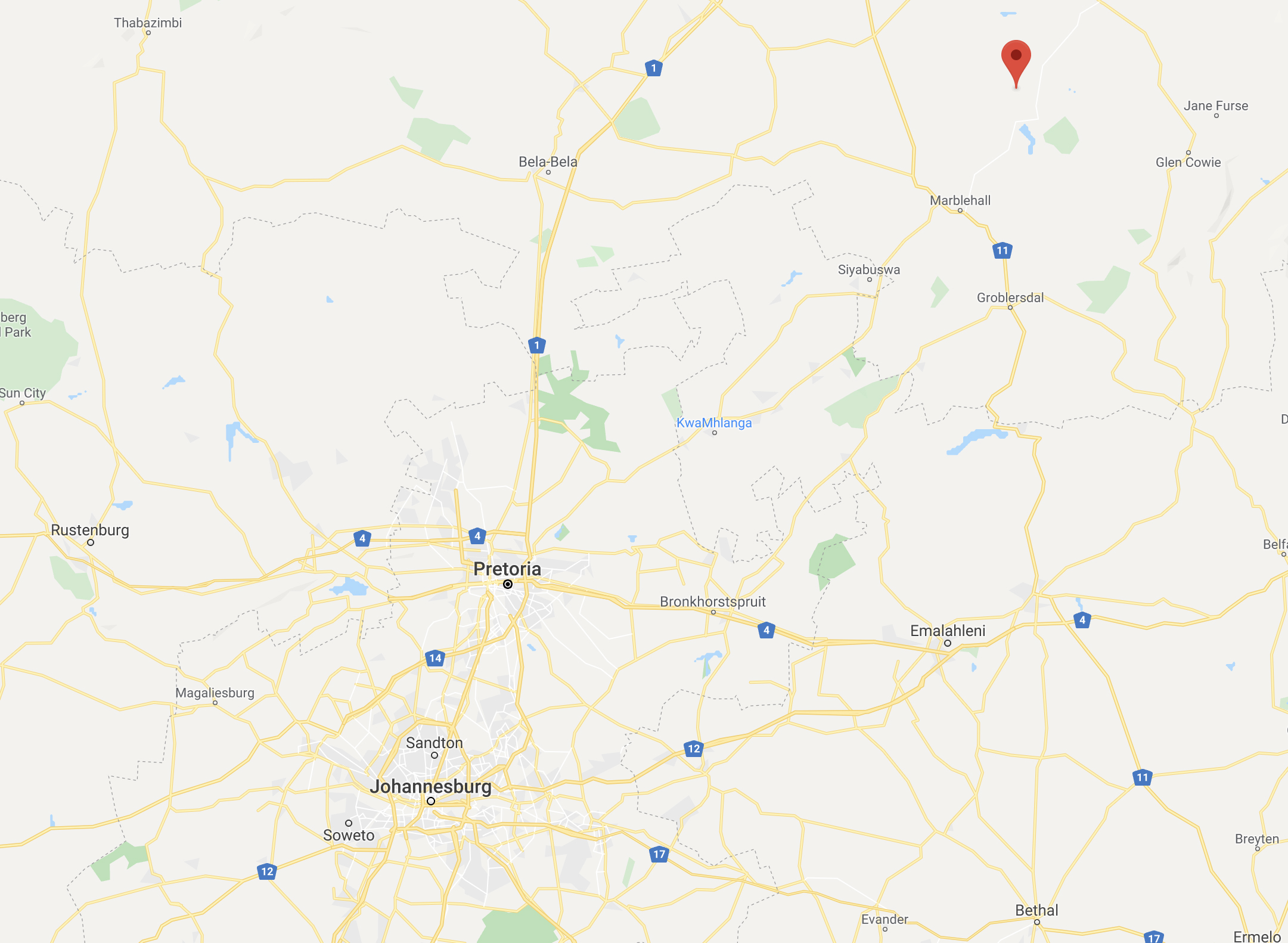

Villagers on the eastern side of the river, north of the farming and granite-mining town of Marble Hall, access basic services such as social services, health, ATMs, police station and other amenities in Elandskraal, located on the opposite bank.

There are no pedestrian bridges over this part of the Olifants. A return taxi trip to Elandskraal via the R579 costs up to R50. With public transport being erratic, a single trip can take hours. And with high unemployment and resultant poverty levels, very few can afford the fare.

That leaves the river. But, as Leshaba found, crossing it can mean a potentially fatal encounter with a crocodile.

With the arrival of the rainy season there are fears that rising water levels might see more attacks.

One of the spots where people cross the Olifants River when travelling between Elandskraal and Mogalatjane in Limpopo. Several people have been attacked by crocodiles while crossing the river. Photo: Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media

“They [the crocodiles] have laid eggs. Goats are disappearing and we are worried,” says Jacob Mammekwa, ward committee member in the Ephraim Mogale local municipality, who has been part of efforts to catch and remove crocodiles.

Leshaba stands on the bank of the river recounting his horrifying encounter: “I just felt something grabbing my arm.”

He knew he was in the jaws of a croc when, with his other hand, he felt its hard, slippery skin. After a struggle, he managed to force the reptile’s jaws slightly ajar. The creature let go and slipped beneath the flowing waters.

Two acquaintances travelling with Leshaba carried him out of the river. His pants, which he’d put over his head to keep them dry as he swam across the river, had been swept away, along with his cell phone and documents.

But Leshaba, who was treated for his injuries in Matlala hospital, is grateful to have escaped with his life.

Kolokotela is one of the villages that lie along the Olifants river. Some residents believe the name is adapted from the term crocodile because the reptiles have been terrorising people crossing the Olifants River. Photo: Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media

Last month, 39-year-old Mavis Mohlala was not as fortunate. She was attacked and killed by a crocodile while crossing the river from Kolokotela (a name believed to derive from the word “crocodile”) while on her way to church.

Mammekwa says more than 10 people have been either killed or mauled by crocodiles in the stretch between the Flag Boshielo dam and villages to the north.

“We are calling on the government to at least build a bridge because, if they do, people will cross without injuries,” he says. “Those who come to the river to fish, it is their own problem, because we told them not to play by the river. But those who cross are innocent people, they need the government, they need our help to have a bridge.”

The river offers unemployed people a chance to make a living from fishing. But the men who sell their catch in the villages have also been terrorised by crocs.

Wilfred Mudzamatira looks at the spot where he fought a crocodile while submerged underwater for about 10 minutes while fishing in the Olifants River. The reptile eventually let go of him but he carries deep scars from that encounter. Photo: Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media

Fisherman Wilfred Mudzamatira, who lives in Elandskraal, bears deep scars on his thigh. He was standing hip-deep in the stream, casting his line, when he felt sharp teeth sink into his flesh. He was dragged out into deeper water.

“My friends ran away,” he says, recalling the incident with a smile.

“We fought for about eight minutes. I punched it and punched it. Then it made a mistake to open its mouth slightly. That’s how I escaped,” he recalls.

Wilfred Mudzamatira looks at the spot where he fought a crocodile while submerged underwater for about 10 minutes while fishing in the Olifants River. The reptile eventually let go of him but he carries deep scars from that encounter. Photo: Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media

He seldom fishes now, but doesn’t fear crocodiles.

“A crocodile is a very stupid animal,” he says, shaking his head. “It just wants to bite and pull you. It can’t do anything else.”

In 2017, during a spate of croc attacks, Mammekwa rallied the Department of Environmental Affairs to help trap the reptiles. The project proved successful, but then encountered a problem.

“We caught the first crocodile, the second and the third one. But then … other people were coming at night to steal the crocodiles from the traps and sell them to traditional healers,” explains Mammekwa, who is also a farmer.

Word got around the region that the carcass of an entire crocodile could fetch over R10,000, allegedly from healers. The thieves became so brazen they were wading into the river to remove the traps and animals before fleeing.

Wild animal parts, including those of crocodiles, are used for medicinal purposes by certain traditional healers. It is also believed that the reptile’s brain and bile can make lethal poison.

“We heard they were selling the fat from the crocodiles. They were also selling that head for R1,000, the skin and also the meat. We heard the total amount of a crocodile is up to R15,000,” says Mammekwa.

The project was abandoned prematurely as a result of this activity, though no one was arrested for theft or illegal sale of reptiles.

“We decided to stop the project to avoid further problems,” he says.

In 2015, in a Mozambican village, 62 people were killed after consuming beer believed to have been laced with crocodile bile. But a leading Zimbabwean pharmacologist who did a study on crocodile bile dismissed the crocodile bile poison as “a rural myth”.

The human-wildlife conflict is not only restricted to the Elandskraal area and crocodiles. It is a global phenomenon involving, notably, crop-damaging elephants and livestock-killing predators.

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation – in a report titled Human-Wildlife Conflict in Africa – causes, consequences and management strategies – says the crocodile appears to have superseded the hippopotamus as the animal responsible for most deaths on the African continent.

The 2009 report says crocodile attacks are common because numbers of large crocodiles are high throughout the continent and their distribution range is wide. Also, crocodiles can live in close proximity to people without being detected – unlike lion and elephant – and their numbers recover quicker than those of other killers.

Myths, legends and rumours abound in Limpopo – including one about a large crocodile whose body is covered in a binding of chains. Fishermen have named this beast – which they claim to have spotted on the river bank – after WWF wrestler John Cena.

Another story is that the large crocodile population is the fault of a disgruntled white man who, when his tourist lodge wasn’t doing too well, dumped a large number of reptiles into the river under cover of darkness.

Zaid Kalla, spokesperson for the Limpopo department of environment and tourism, says the provincial government regrets the loss of life in the area. But he argues that a growing number of crocodiles is a sign of good environmental management and that communities should respect wildlife habitats.

“Our community members are not constrained to cross rivers and swamps as there are routes connecting villages. Members of the communities are often found neglecting utilisation of availed routes in preference to shorter and life-threatening options,” says Kalla.

“Community members also unintentionally endanger their lives by swimming, crossing and even fishing in very hostile habitats in close proximity to wildlife,” he says.

Kalla says the department will continue to educate and warn communities about wild animals. MC

Lucas Ledwaba is the Editor of Mukurukuru Media.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider