Joburg International Film Festival

Hero: The story of a Caribbean man in Africa’s independence struggle

A film about a decorated World War II pilot from the Caribbean, a lawyer, and then a man integral to independence on the African continent, is a headliner at the Joburg International Film Festival. Speaking with the filmmaker triggers much more thinking about history and hidden heroes.

Too often, discussions about race and the African Diaspora have a one-way feeling to them. They become the story of Africans forcibly transported elsewhere, then turned into chattel slaves for the remainder of their days and then those of their children’s as well. Then the emancipation from slavery in the Caribbean and North America comes about (almost as if by a mysterious deus ex machina), followed by civil rights struggles and political upheavals. What is usually left out in this is the complex interplay between the people of the African Diaspora and of Africa itself.

On the display of family photographs in the hallway of our Johannesburg home, a display curated by my wife, there are family portraits from both of our families. In her case, however, displaying them has also been an effort to reclaim a history that, too often, has been rubbed out by the more usual, dominant colonial historical storyline of South Africa.

There are unusual photographs of some early 19th century forebears, representatives of the complex mix of people who became today’s coloured South Africans. But, rather than subservient farmers and retainers, these pictures show young men who were ambitious students at those early mission stations in the Cape.

Then, in the 20th century, there are more pictures, but of the men in uniform who answered the call to the imperial colours to fight for Britain in France in the First World War, and then in North Africa during the Second. From their respective journeys, they could glimpse a society that would be put together very differently than the one they had come from, and there was even the possibility of forging lifelong friendships that transcended South Africa’s increasingly rigid colour line.

And, of course, in his own way, in recapturing stories like this, author Fred Khumalo did a massive service for South Africa by casting a bright light on the once-hidden sacrifice of the southern African men on the Mendi (from his novel Dancing the Death Drill and the dramatic work that evolved from it) who perished in a ship collision, en route to their service on the Western Front.

Looking more broadly, now, from the beginning of the 20th century, the flow of people with ideas and inspirations has also moved from the Western Hemisphere to Africa, and to Europe and Britain – and vice versa. Consider the varied and wide-ranging impacts, just for starters, of people like George Padmore, Frantz Fanon, Peter Abrahams, Langston Hughes, Es’kia Mphahlele, Marcus Garvey, Ralph Bunche, Kwame Nkrumah, and WEB DuBois (go ahead, look them all up), as they came from their different spaces and cross-fertilised the ideas of African (and African-American and Caribbean) liberation from their different experiences and world views. We might even toss the Rasta culture into this mix too, considering its attractions to people in Europe, the UK, the Americas, and Africa.

For this writer, one of the most intriguing figures has long been John Robinson, a man whose story is now largely forgotten, but, who in the 1930s became a legend in parts of Africa and among African Americans both.

Born poor in Mississippi, by the early 1930s he had gained an aeronautical engineering education, owned a general aviation airfield outside Chicago, and moved easily among black intellectual and cultural circles in his adopted city.

One day, he happened to overhear the conversation of an Abyssinian medical student studying in Chicago, and especially the student’s vivid description of the impending conflict between Abyssinia and fascist Italy. Robinson found himself desperate to volunteer to join the fight on behalf of Africa and against the invaders. He became the Abyssinian emperor’s personal aide and pilot, even commander of that country’s tiny air corps.

The Italians won that war, of course – as it was the most advanced bombers of the time versus troops largely armed with a desperate mix of antique weapons. But upon Robinson’s return to the US, he was greeted by thousands in a parade that wound its way through New York City. During World War II, he helped train the Tuskegee Airmen and then, post war, he returned to Ethiopia to help set up the country’s first airline, before perishing in a fatal test flight. There surely must be a film, a play, or a novel in this man’s life.

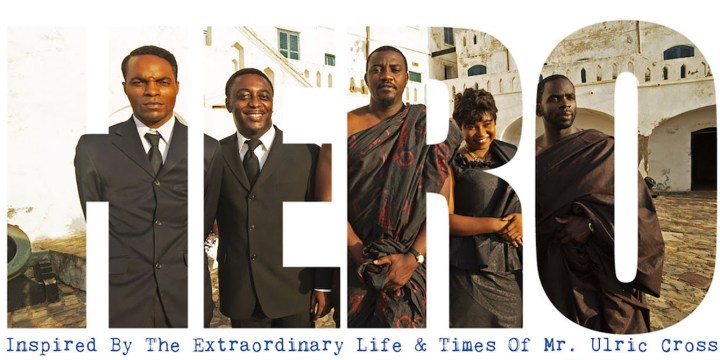

And then I encounter Frances-Anne Solomon, the Caribbean-born filmmaker. Solomon has found her own amazing tale worth telling, in the film Hero, that depicts the equally extraordinary life of Ulric Cross. Solomon’s film had an appearance at the Durban Film Festival this year, but it is now back for the Joburg Film Festival for more showings to South African audiences, after having been shown at film festivals across Britain.

Ulric Cross was a Trinidadian-born war hero, judge and diplomat. In his military service, he became the most decorated Caribbean pilot serving in the Second World War, and that service was followed by a career as a lawyer and judge, working in the independence movements of Ghana, Cameroon, and Tanzania.

After World War II, Cross was recruited by George Padmore to work on a post-colonial legal system in Ghana, and then he was sent on to Cameroon, and later to Tanzania. Solomon observes that for Caribbean persons not used to seeing the Caribbean world as something deeply connected to Africa’s emerging modern story, a film like this is a link to the larger forces of global events.

Solomon explains that her film is a quest, a hero’s story, a road movie (from Trinidad and then all across Africa), but it is also a love story. Perhaps even a bit of a journey into the heart of darkness as well, during Cross’s time in Leopoldville in the Congo, in 1960.

In making her film, Solomon recruited a cast that brought together African, British, Caribbean and North American actors, as well as using on-location settings and archive footage for some exterior shots. The resulting work has garnered praise from critics and festival awards alike. As the Evening Standard said of it, “If you are interested in the birth and evolution of Pan-Africanism, you’ll be gripped.”

In speaking with Solomon about her film, her life, and her craft, she says she came to the story of Hero because it was handed to her by her ancestors. A dying family friend had told her mother, “Tell the story of Ulric Cross”, an elderly member of Solomon’s own large, extended family, and so Solomon’s mother took on the task of raising the necessary funds, despite no experience as a film producer.

Solomon already had a busy life as a film producer/filmmaker for the BBC, as well as other work, and so, taking on this work took some time, and the actual project itself took some eight years to complete.

The director says her mother remained a constant goad to her, the filmmaker, and was critical of any efforts to “juice it up”, in order to make it more exciting than it already was. Not surprisingly, given these efforts at telling the truth about an authentic Caribbean hero, the film was screened first in a Trinidad (or “Trin’dad” in Solomon’s local lilt) festival. “It was important to me,” to do so, she says simply.

Solomon says audiences have liked it a great deal, and she says historians have been supportive of the finished product as well. The film has a kind of karmic quality, Solomon explains. From Africans carried unwillingly to the Caribbean, “We, who were taken from West Africa under these deplorable conditions four hundred years ago, we were able to return to Africa for healing”, a kind of “Middle Passage”, but in reverse.

Ulric Cross, said one Ghanian politician to Solomon as she was working on the film, “didn’t come to help; Ulric came to learn”.

The response to her film, black versus white, has been strikingly different. After seeing it, some audience members, black, have said to Solomon, “your film has changed my life”, while white audiences have been decidedly more blasé, she says.

But, she explains that she made this work for a particular audience – for her people. Is it myth-telling or truth-telling? She says myths grow out of truth-telling. We can agree on Black Panther’s relative lack of truth-telling, in contrast to, say, a real hero, although the success of that film tells us much about the need, even the hunger for heroes, for truth-telling, and for myths. And that moves us to discuss another recent film, Green Book. Of that film, Solomon asks, can someone make a film about the black experience who is not black themselves? In answering her own question, she says that there remains a need for black filmmakers to tell their own stories, black stories, themselves.

The Joburg Film Festival’s six-day celebration of 60 films from across the globe began on 19 November. Screenings are in six venues throughout Johannesburg, including Nelson Mandela Square in Sandton, Ster-Kinekor in Sandton City, Cinema Nouveau in Rosebank, Maboneng’s Bioscope, and Kings Theatre in Alexandra.

Hero will be screened, followed by a question and answer session, on Thursday 21 November at 8pm at the Theatre on the Square, Nelson Mandela Square. A second screening, also with a Q&A, comes on Saturday 23 November at 6pm at the Kings Theatre, Alexandra. A final showing is on Sunday 24 November, at 3.30pm at Cinema Nouveau in Rosebank. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider