Maverick Life

From Innovation to Implementation: Artificial intelligence and the African context

As artificial intelligence moves out of the labs and into our hands, what are we going to do with it to address societal challenges in an African context?

The vosho was arguably the most ubiquitous South African dance move of 2018, possibly even 2017. By 2019’s Youth Day celebrations, President Cyril Ramaphosa partook in what has become a South African tradition, the politician’s get-down, by attempting a rather inelegant and amusing vosho on stage. The dance move is made extra tricky by its combination of co-ordinated kicks, squats, and simultaneous movement of all four limbs, done at a particular speed, to a beat.

“It’s a thing that is quantifiable; you know what is a good vosho and what is a bad vosho. We watched several vosho videos and ran analytics on them. We worked out what is a good speed to descend at, how low should you go relative to your body height, and how quickly should you come up as well. We created a spreadsheet with all the data and then we created a formula that can rate how good one’s vosho is,” says Babusi Nyoni, a 31-year-old self-taught design strategist, innovator and co-founder of digital agency Triple Black.

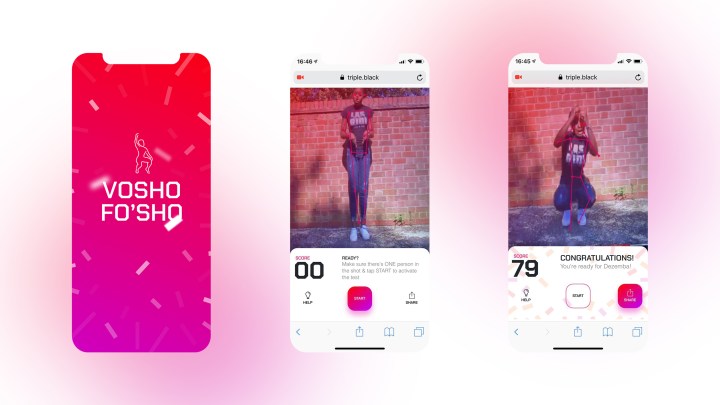

He is referring to Vosho Fo’Sho, an experimental browser-based app he created in 2018, which uses cutting-edge pose estimation technology to rate a user’s vosho moves — something Ramaphosa might benefit from. The app uses TensorFlow, an open-source machine learning library developed by Google Brain, the deep learning artificial intelligence research team at Google.

“The software allows us to do pose estimation through your smartphone or computer camera in real time with no sensors and no need to put special stickers on parts of your body. It can basically map every part of your body using your device’s camera, and we decided to do something kind of cool and social with that,” explains Nyoni.

“The app was accessed on over 100 different device types during the December period and the feedback was really amazing.”

Almost a year after launching the app, on 31 October 2019, Nyoni attended the inaugural TensorFlow World conference in Silicon Valley, in Santa Clara, California. He was invited to speak about the app, and more importantly, the use of its technology beyond rating dance moves, to potentially diagnosing Parkinson’s disease.

“We tried to think of a use case that could also benefit from pose observation over time using the formula we built to rate the dance move, and we discovered that Parkinson’s disease diagnosis also partially relied on the symptomatic observation over time of the parameters that we were already able to measure through dance. So it was very easy to then translate those formulas to a Parkinson’s use case, and of course, we had to acquire footage of people with Parkinson’s walking, which is still something that we’re training the formula on,” says Nyoni.

His talk at the conference was also attended by the team behind TensorFlow, the artificial intelligence software that made the vosho app possible.

“I had a call with the product lead for TensorFlow last night actually, and they’ve thrown their weight behind our Parkinson’s disease diagnosis tool. We’re working towards building a market-ready version before a major Google conference next year.”

The talk was also the last leg of a year-long speaking tour that saw Nyoni visit Oxford, Paris, Geneva, five counties in Kenya, as well as the Fak’ugesi African Digital Innovation Festival in Johannesburg.

Image courtesy of Babusi Nyoni

The idea of using technology to go beyond entertainment is one that is dear to Nyoni. In 2016, while living in Cape Town and working at advertising agency M&C Saatchi Abel, he created the “Banternator”, dubbed by Forbes magazine as “the world’s first artificially intelligent football commentator” for a Heineken campaign. It was an artificially intelligent Twitter bot that was able to respond in real time to football fans, giving contextually relevant banter.

“Once the campaign was done, we just shelved it and as someone who is always looking for sustainable ways to innovate, and to have an impact beyond the now, I was taken aback by how transient innovation can be within the advertising space. According to my perception, this was a successful technological innovation with potential for further application,” says Nyoni.

A couple of months later, he went back to the tech and the formula they had built to punt beer and repurposed it to build a prototype that would predict potential refugee crisis scenarios in Africa. It caught the attention of the Innovation Service at the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), where Nyoni is engaged as a consultant supporting user experience (UX) and artificial intelligence projects remotely. The team works with similar technology on a project that assists with predicting the movements of displaced people in Somalia.

The prototype used data from sources such as the World Bank to look for similar patterns in areas that had experienced conflict that eventually led to a refugee crisis.

Says Nyoni: “For example, I noticed in my research that for places like Syria and Rwanda, before major displacement events occurred there would be dips in the stats on CO2 emissions. My approach at the time was not informed by a deeper understanding of the data and what that data means, it was really me coming as a designer and looking at patterns. What I discovered later, was that the drops in CO2 emissions were caused by things like factories closing up, and people were not going to work any more, and how that might signal potential unrest, or something leading up to a point where people might be displaced for economic reasons.”

In 2017, Nyoni, who had been based in Cape Town since he moved there in 2012 from his home country, Zimbabwe, once again packed up his life and moved to Amsterdam, where he currently lives. One of the primary reasons he made the move was to be in a position to make enough of an income to be able to fund the projects he is passionate about, projects that external funders might not immediately see an opportunity in. Fellow Triple Black co-founder Dr Natalie Dixon, a South African, also made the move to Amsterdam, while the third co-founder, Robert Scott, is based in South Africa. What remains key for the team is to create solutions that work in an African context.

“We self-fund 100% of what we do in the hopes of improving the African lived experience by creating systems and solutions for and by Africans,” says Nyoni. “When I was touring in Kenya, my series of talks revolved around Africa’s inclusion in the economy of tomorrow, which is one that is led primarily by technology, such as artificial intelligence.

“We need to demystify the tech to make it as approachable as possible, which is partly why I did things like the vosho app and AI-generated gqom music: to make technology ‘ratchet’ in order to make it acceptable. My goal is to do things with new technology that are so African that future versions of myself won’t even think twice about approaching the tech. Additionally, what are all these very African things that we should start imagining now with existing technology that will benefit us, before other people do the job for us?”

The agency’s latest project, “our favourite child” as Nyoni calls it, is Sis Joyce, an artificially intelligent chat bot that connects users to medical advice as well as medical professionals through chat apps.

“We have a network of doctors in Zimbabwe, a country with one of the highest doctor-patient ratios in the world and a crumbling healthcare system. What we’re able to do is connect doctors to patients on chat platforms like Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp. But because of the scale at which we operate, and because of the lack of feasibility of directly connecting doctors to patients, we have this intermediary artificially intelligent nurse which handles the top-level conversations required before you get to a doctor.”

The service is available in eight countries: South Africa, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda and Malawi. One of the challenges it addresses is the cost of data in some African countries. According to Zimbabwean tech website Techzim, Zimbabwe now has the most expensive data in the world.

“What that means for many people is that getting online is limited to Facebook and WhatsApp. It’s too expensive to leave their social media ecosystem to visit Web MD or any other online doctor-patient platform. So, we go to them on the platform that they’re using and provide them with something that resembles a very real, tangible experience of speaking to a doctor.”

Nyoni says the service is not meant to replace a doctor, and the disclaimer is given to users at every stage. And depending on the symptoms, the nurse, Sis’ Joyce, often recommends patients go see a doctor.

The service is currently free, and the doctors who are part of the service also offer online consultations, volunteering their time and expertise.

“We would like to keep the platform free because we’re also targeting people who generally don’t have access to healthcare or otherwise wouldn’t think of approaching doctors with things like that. Whereas people in the Western world would have a cold and call the doctor up, you have people in sub-Saharan Africa who go through much worse health conditions before they decide it’s time to see a doctor.

“Many of the questions that people are asking are also of a sexual health nature. So we’re seeing a lot of the taboos around how people relate to their bodies and other people’s bodies being broken. To be able to ask the questions anonymously and get an instantaneous response, is something that the users of our platform really appreciate.”

A little more than a year ago, in September 2018, the New York Times published an opinion piece by Dr Kai-Fu Lee, a Taiwanese-born American computer scientist, author and businessman with an impressive resume that includes being former president of Google China, as well as former vice-president of Microsoft’s interactive services division. In it, Lee argued that artificial intelligence, like other technologies before it, had now moved into the age of implementation.

“Every technology goes through an age of discovery and an age of implementation. During the age of discovery, the critical work takes place in research laboratories, where scientists make the breakthroughs that move the field forward. During the age of implementation, the technology reaches a point of practical utility and begins spilling out of the lab and into the world,” he wrote.

He argued that in this age, partly due to the sheer amount of data, as well as the enthusiastic embrace of AI in China, that country stood a chance of overtaking the US and becoming a leader in AI. In another article, he compares AI right now to the early stages of electricity. Once upon a time, electricity itself was what seemed magical; however, the primary focus today is not on the wonder of electricity, but rather its many applications. This, he imagines is the future of AI, where society is no longer focused on how amazing the tech is, but rather on its uses. The tech itself becomes something anyone can use.

This is a point of view Nyoni agrees with strongly:

“The thing that we loved about the feedback we got from the vosho app was that at no point did anyone give us feedback along the lines of ‘this is cool tech’ or ‘this is nice computer vision’, it was all related to how it rated dance moves, because in the end all that matters when it comes to technology is context.”

Nyoni himself didn’t go the tertiary route. Everything he knows and practises is self-taught. When he finished school in Zimbabwe, due to the economic recession, tertiary education was not an option.

“I started working for a security company in Bulawayo, then at an internet café; I also used to paint houses, and do the electrical installations in newly built homes. I did a bunch of stuff before I decided to go back to my creative roots, because as a kid I used to sketch all the time. So I tried to be the best creative in Zim… eventually, through my portfolio on Behance, I became the most viewed and appreciated Zimbabwean creative on the platform.”

Nyoni then moved to Cape Town in 2012 and started working for a small agency.

On noticing the shift towards the importance digital skills, he decided to focus on his coding skills.

“I would get home every single day, between Monday and Thursday night and open my laptop, watch tutorials and code things and go to sleep at 4am and wake up at 6.30/7 o’clock for work, every single week for four days a week. I did that for a whole year.”

At the end of that year, Nyoni was developing mobile apps and making his own WordPress themes to sell.

That self-taught approach, and the view that tech is a merely a tool to learn and apply to different problems, is part of what drives Nyoni and Triple Black Agency.

“No one goes on about tech anymore. You know, in the mid-2000s it would have been cool to say ‘this is powered by x’. But technologies have become so ubiquitous that the differentiating factor now is how it feels when you put it in in someone’s hands.

“At present, what’s going to drive us to the next point as everyday Africans is not the PhD in computer science and data science. Rather that people understand technology enough to be able to solve problems with it right now,” says Nyoni. ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider