MAVERICK LIFE

If memory serves us well: Understanding the distortion of events in the digital age

How do we come to believe that ‘truth isn’t truth’, Nkandla has a great fire pool, the press is ‘the enemy of the people’, the ‘deep state is plotting against Trump’ (hello, QAnon) or that in the heart of every reputable news organisation sits a disinformation cabal? We investigate.

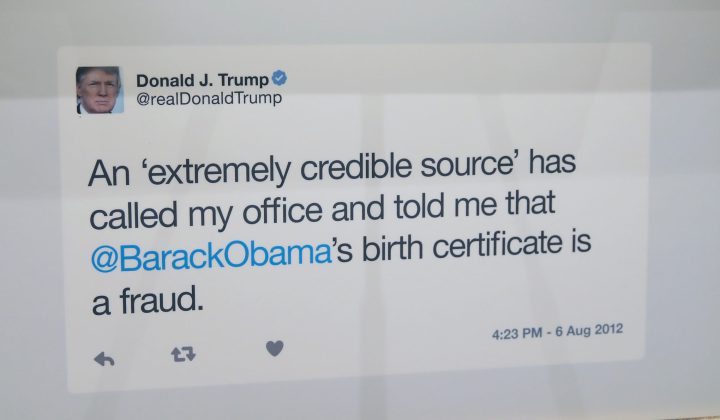

Do you remember when now US President Donald J Trump declared that then-president Barack Obama was born in Kenya? As absurd as it sounds (and as bogus as it is), five years after the claim, an NBC News-SurveyMonkey poll in 2017 showed that 72% of registered Republican Party voters were still not sure if Obama was, in fact, a US citizen. Seventy-two percent. Five years and one US birth certificate later.

If fake news, conspiracy theories and lies can hold so much grip on our minds and conversations, it is because social media spread them like bushfire, but also because humans can transform fake information into fake memories, especially when the fabricated details align with our system of values and political beliefs.

Dr Kevin Thomas, associate professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Cape Town, says that “memory is not like a computer hard drive, in the sense that all of our past experiences are not filed away, in pristine form and secure storage, waiting for us to click on them so they can be replayed in the way that we click on video files and then watch a movie. Instead, memory is a lot messier than that.” He breaks the process into four steps: encode, consolidate, store and retrieve.

“I use this analogy: imagine that laying down a memory (ie, going through an experience) is like baking a giant chocolate chip cookie. You put all the ingredients together, you bake it in the oven, and it eventually emerges with a wonderfully evocative picture. You can just imagine the smell and taste. That whole process is what we call encoding. But now the memory trace has to be consolidated and stored. And this process actually means it has to be broken down into its component parts (the visual aspects: what does it look like?; the temporal aspects: when did it happen?; the spatial aspects: where did it happen?, and so on), so that each of those can be processed in the area of the brain specialised for processing that kind of material, and then stored in the brain region specialised for storing that kind of material.

“So, now your chocolate chip cookie is broken down into crumbs. Imagine holding it in the flat of your palm, and then closing your fist around it, crushing it and allowing all the crumbs and the chocolate chips to scatter on the floor. Some of those crumbs and chips will be relatively far from one another, whereas others will be relatively close by. This means some aspects of the memory are relatively likely to be retrieved together, and some are not,” he says.

The process of retrieval is even more complex.

“Let’s say you want to recall that memory. You have to put the cookie back together. The process of retrieval means gathering the crumbs and chips as best you can and patting them together in the best facsimile of the original cookie as you can. Will the reconstituted cookie be identical to the cookie you took out of the oven? Definitely not – some crumbs will be lost, some will be in the wrong place, and so on. Will the reconstituted cookie look like the one that came out of the oven? Probably.

“The better your ‘memory’ (ie, the better your retrieval strategies), the closer the match between the original and the reconstituted cookie. But they will never be 100% identical. And that, ta dah, is why all memories are reconstructed versions of our past experiences”, says Thomas.

A practice called the “illusory-truth effect”, in which a detail or event is repeated over and over again to form a new “truth”, is often used in politics. A study titled “Knowledge does not protect against illusory truth”, and published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, explains that:

“Repetition may be one way that insidious misconceptions, such as the belief that vitamin C prevents the common cold, enter our knowledge base. Research on the illusory truth effect demonstrates that repeated statements are easier to process, and subsequently perceived to be more truthful, than new statements”.

In one episode of the mini-series Chernobyl, the protagonist, Valery Legasov, says:

“What is the cost of lies? It’s not that we’ll mistake them for the truth. The real danger is that if we hear enough lies, then we no longer recognise the truth at all.”

Repeated lies, “alternative facts” and conspiracy theories have become frighteningly common practice in international and local politics. This, of course, isn’t anything new; weird theories, falsehoods and dishonest comments have always punctuated the political discourse.

Yale professor of philosophy Jason Stanley noted in his article “How fascism works”:

“The key thing is that fascist politics is about identifying enemies, appealing to the in-group (usually the majority group), and smashing truth and replacing it with power.” But the fact that they are now being widely spread and at a more frantic, internet-pace thanks to social media is way more impactful… And alarming.

“History is always by consensus,” says Thomas.

“So, we accept that something has happened, if you and I have been there, if we’ve done it together, and we agree that this is what happened. That’s a consensus agreement that this is the memory of what happened.

“Now, where people can distort it, is by saying, well, your experience of it was that, but my experience of it was this – now we have a disagreement. And so, there’s no consensus any more, so we can equally and powerfully hold on to what we say is the memory of it.

“When you have politicians and other people who are willingly distorting that memory by just filtering information into the media and through social media […] what they’re doing is, they’re constructing a narrative that’s designed to confuse matters; or that is designed to just play to a particular group of people that will believe that and will say, ‘Okay, we have a consensus that this is what happened, that this memory’.

“It’s very easy to distort memories […]. If I told you over and over again that something happened, eventually you might come to believe that that thing actually happened, particularly if your own memory is not very strong or you don’t have other people around you that are drawing that consensus in.”

The US president branding the press as “the enemy of the people”, “fake news” or his comments, among many, that: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people”, are dangerous because they build a narrative that sticks into our collective memory, sometimes even transforming what we remember.

So are the EFF’s nasty tweets and comments repeatedly attacking individual – mostly female – journalists, and naming them “evil”, or fake information being widely released and wildly publicised by pro-Brexiters ahead of crucial elections that eventually lead to Brexit.

Thomas adds that, “People can exploit gaps in memory. There are certain politicians in the world, or just unscrupulous people, who use […] people’s gullibility and willingness to go along with a narrative that’s constructed; they know if you bombard somebody with a message over and over and over again, eventually it becomes a part of their history and it becomes a memory; and people hold on to those memories, because for most [of us], things have to make sense; people have to make sense of a story.

“Memories are supposed to be a consensus process where we agree that this is what happened. But sometimes you’re just simply accepting the fact that what he says is truth and reality; it’s not a consensus any more. It’s one person imposing their whole vision of the world, on a whole group of people. And those people are willing to go along with it because they feel like this is a vision that they want to buy into.”

A 2018 report by Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy and Sinan Aral titled, “The spread of true and false news online”, found that, “False news reached more people than the truth; the top 1% of false news cascades diffused to between 1,000 and 100,000 people, whereas the truth rarely diffused to more than 1,000 people. Falsehood also diffused faster than the truth”.

In his post-obit book of essays, The River of Consciousness, Oliver Sacks writes that “There is, it seems, no mechanism in the mind or the brain for ensuring the truth…. We have no direct access to historical truth … no way by which the events of the world can be directly transmitted or recorded in our brains; they are experienced and constructed in a highly subjective way…. Our only truth is narrative truth, the stories we tell each other and ourselves — the stories we continually recategorize and refine.”

And indeed, our creative brain is also able to distort events and sometimes even create new ones. An article in The Conversation explains that the term “The Mandela Effect” was coined in 2010, by paranormal consultant Fiona Broome when she realised that “countless people on the internet falsely remembered Nelson Mandela… had died in prison during the 1980s” – while, in fact, Nelson Mandela died in December 2013. The phenomenon was even turned into a movie and the term has been widely used to explain the collective misremembering of common events.

Some misconceptions can be benign: the famous quote from Disney’s Snow White, “Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?” is in fact, “Magic mirror on the wall, who is the fairest one of all?”; and among all the memorable quotes in the movie Forrest Gump, one seems to have left a special imprint in our collective memory – “Life is like a box of chocolates,” says Tom Hanks, seated on a bench waiting for the bus; except that the real words are, “Life was like a box of chocolates.” Similarly, people often remember Rich Uncle Pennybags (aka Mr Monopoly) wearing a monocle; he doesn’t. And C-3PO being a head-to-toe gold and goofy robot? His right leg is silver. And it has been silver all along.

Other misconceptions can be more problematic: many remember that only four passengers were in the limousine driving John F Kennedy on the day of his assassination. There were six.

Such errors can have serious consequences, like in the case of eyewitness-identification testimony; multiple studies have found this form of evidence to be very unreliable.

US writer, filmmaker and political activist Susan Sontag once said, “What is called collective memory is not a remembering but a stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds”.

Defending truth has never been so imperative. ML

This story was first published as a newsletter. You can subscribe to Maverick Life’s weekly newsletters (sent out every Sunday) by clicking here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider