OUR BURNING PLANET: SPECIAL REPORT

Greenpeace in far-flung voyage to conserve hidden life

The environmental organisation launched a global campaign called Protect the Oceans to secure a Global Ocean Treaty at the UN, which would protect 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030, preserving vulnerable marine life and encouraging sustainable fishing practices.

MOUNT VEMA: When you get to Mount Vema there’s nothing much to see. From the deck of the Greenpeace ship the Arctic Sunrise, it’s all seabirds, waves and the odd whale blowing in the distance. But below the surface, life abounds.

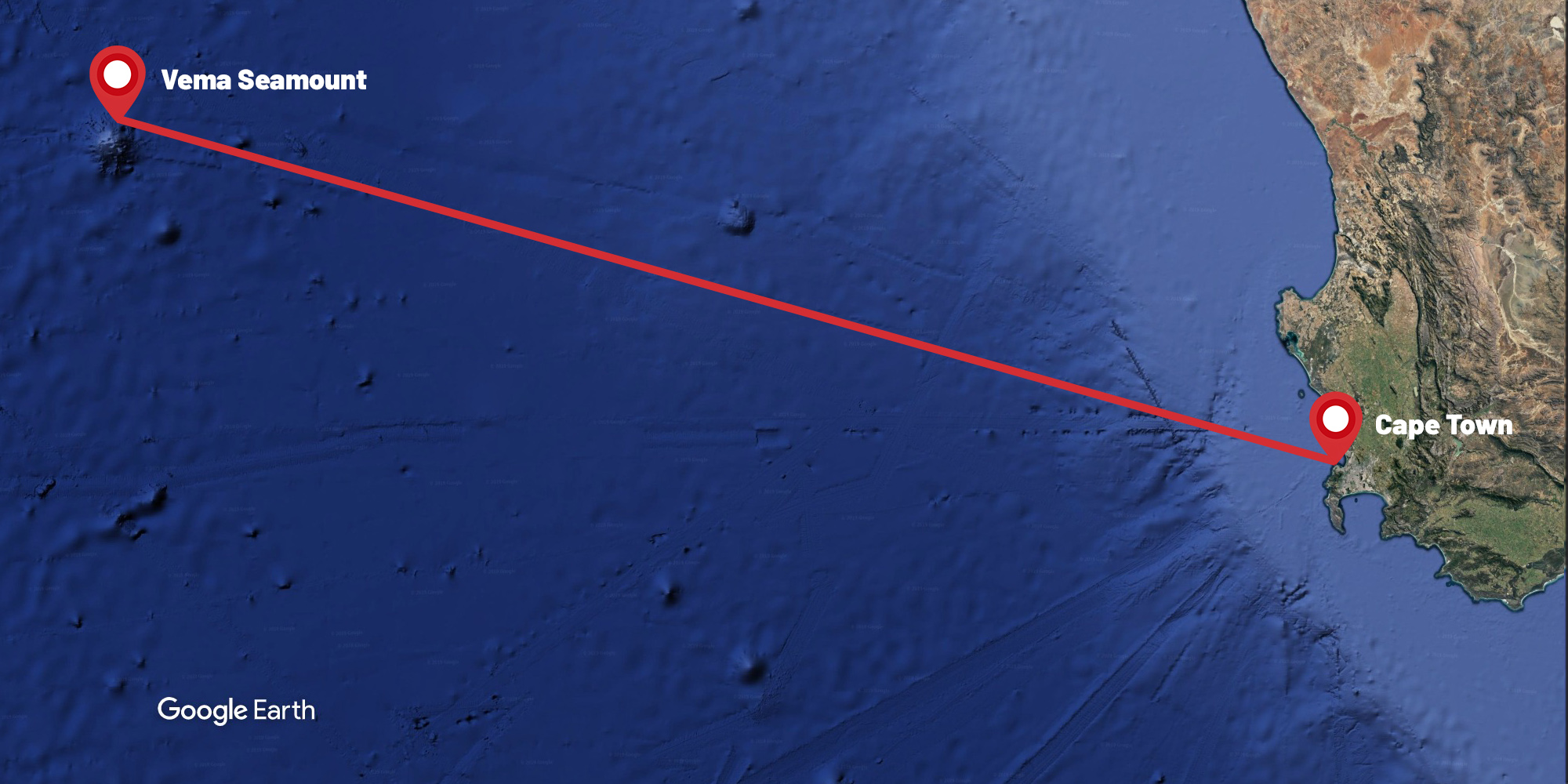

Daily Maverick joined the Greenpeace team for a week at sea, visiting Mount Vema, an underwater seamount, in November 2019. Mount Vema’s highest peak reaches 7m below the surface and is a biodiversity hot spot, brimming with tropical fish, kelp and crustaceans. Their presence is a positive sign of recovery after the area was declared a marine protected area in 2007, following brutal over-fishing in previous decades.

Map: Aisha Abdool Karim

Climate and Energy campaigner for Greenpeace Africa, Bukelwa Nzimande, says protecting the oceans against industrial fishing, oil drilling and deep-sea mining is an essential part of the fight against the climate crisis and Mount Vema is a prime example of an area that has been able to recover from detrimental human activity through legislation.

“We often speak about forests as the lungs of the planet, but we often forget that oceans also produce oxygen, trap carbon dioxide, and excess heat. The ocean is so important to our survival and it’s shocking but only 1% of our high seas are protected,” says Nzimande.

Greenpeace launched a global campaign called Protect the Oceans, to run from 2019 to 2020, to secure a Global Ocean Treaty at the United Nations, which would protect 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030, preserving vulnerable marine life and encouraging sustainable fishing practices.

As part of the campaign, Greenpeace launched a Pole to Pole voyage from the Arctic to the Antarctic to undertake research and investigations. Their stops have included the Arctic, the Lost City in the mid-Atlantic, the Amazon Reef, which stretches from Brazil to French Guiana, and Mount Vema, 1,000km off the coast of South Africa.

According to Greenpeace, a Global Ocean Treaty could help protect vulnerable marine life and provide a legal framework for the protection of international waters, creating marine sites free from human activity beyond national waters. More than 40% of the planet is high seas, areas beyond national jurisdiction, and Nzimande says they’re fighting for the United Nations Global Ocean Treaty to be “a standard legally binding document that all nations will be called to account for”.

One of Mount Vema’s summits with an extensive canopy of kelp (Ecklonia radiata) which covers an understorey of underwater flora and fauna, some of which may be unique to this specific seamount. Divers found rich marine life at Mount Vema. (Photo: Richard Barnden / Greenpeace)

“Us protecting and pushing for the protection of the high seas is ultimately protecting our oceans and also human health. Human life is also maintained because the high seas assist in replenishing fish stocks along the coast. So it’s really pushing for a connected network that will ensure that the high seas and our coastal areas are healthy,” says Nzimande.

In a report compiled by marine biologists and academics at the University of York, University of Oxford and Greenpeace titled 30×30: A Blueprint for Ocean Protection, researchers broke down the global oceans to show what a global network of ocean sanctuaries may look like. Marine biologist and on-board campaigner Thilo Maack was one of the scientists who helped draw up the blueprint and says that our survival depends on the health of the oceans.

But even if the tide turns and sites are legally protected, implementation on the high seas is a tough ask. Even in an already protected area like Mount Vema, it’s clear that fishing vessels continue to lay down traps on the sly, taking advantage of the abundance of the gourmet delicacy, Tristan rock lobster, otherwise known as crayfish.

A diver jumps from the Greenpeace vessel, the Arctic Sunrise at Mount Vema. (Photo: Leila Dougan)

“On our way here we saw [on the satellite tracks] two long-liners over Mount Vema for 24 hours. We passed by one of these vessels and asked, what did you do there? They said they were moving provisions from one ship to the other, but a different explanation could be that they were fishing here for 24 hours. No one is really controlling this ban on bottom fishing and that’s what we are calling for,” says Maack.

Mount Vema was discovered in the 1960s and has been protected by the Convention on the Conservation and Management of Fisheries Resources in the south-east Atlantic Ocean since 2007, but Greenpeace divers found abandoned fishing gear, including fishing nets and crayfish traps, which they refer to as “ghost gear”. Some of the nets were no more than a year old and continue to trap marine life long after the crew have departed.

There are an estimated 640,000 tonnes of ghost gear that enters the water every year which makes up 10% of plastic waste in the ocean, according to a report released by Greenpeace. Ghost gear comes from legal fishing but also illegal and unregulated fishing and includes nets, traps and lines found in the deep ocean as well as on seamounts, including Mount Vema.

Bottom feeders like the Tristan rock lobster caught in these traps and not removed from the ocean die and become bait for more lobster, “so this trap keeps on fishing, that’s why we call it ghost gear,” says Maack.

Robert Anderson, associate professor at the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Cape Town, looks through an old fishing net that divers found abandoned at Mount Vema. Anderson was on board the Arctic Sunrise with Greenpeace. (Photo: Leila Dougan)

Almost 70% of ocean areas are under severe pressure from climate change, with ecosystems and biodiversity showing rapid decline due to human impacts, according to the report Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, released by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Sea surface temperature changes, ocean acidification and ultraviolet radiation are just some of the shifts that have altered the ocean.

“Everything is getting worse. The sea level is going to be higher than we thought, the temperature is higher than we thought, ocean acidification is taking its toll,” says Maack.

“The concept and the policy on the high seas is that everything is allowed, unless in certain circumstances it is forbidden, and from our perspective it should be the opposite, everything should be forbidden and should only be allowed if a company can prove that for instance exploring gas or oil is not doing any harm to the environment,” he says.

In a report released this year, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services stated that nature is declining globally at rates “unprecedented in human history” and the rate of species extinction is “accelerating, with devastating impacts on people across the globe and the push for sustainable fishing is becoming urgent”.

Moreover, according to the 2018 Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture report, there will be nine billion people to feed by the middle of the 21st century, with fish being an important component of diets globally. The report notes that there was a total of 170 million tonnes in fish production in 2016, with most of it being used for direct human consumption. The persistence of over-fished stock is of particular concern, with an estimated 43% of tuna being fished at “biologically unsustainable levels in 2015”. The report highlights 2020 as the target to end illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

But Mount Vema and seamounts spread around the high seas represent hope for the big blue, and humankind. Maack says that seamounts create sanctuaries for marine species, their safe distance from the coast allowing them to replenish undisturbed.

Feather-shaped hydroids, bryozoans (moss animals), algae and sponges carpet the upper slopes of Mount Vema. Divers found rich marine life at Mount Vema. (Photo: Richard Barnden / Greenpeace)

Over the course of three days, the Greenpeace team collected seaweed and kelp samples from below the surface for Robert Anderson, associate professor at the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Cape Town. Anderson says kelp plays a very similar role to trees and plants on land through trapping carbon dioxide, providing shelter for life underwater and being a source of food.

“Seamounts and remote places like this are refuges for a lot of other species. So, having a healthy kelp forest here indicates that the place is healthy and things can survive here and maybe move to repopulate other areas. Every bit of environment you protect increases your insurance against climate change,” he says.

Maack says Mount Vema is a perfect example of how important it is to allow nature to recover.

“This area was once overfished, the Tristan rock lobster population was completely fished out, but now there’s life here. So it really makes sense to protect this area for future generations. Climate change affects us all. And marine protection is protection against the effects of climate change.”

A small group of sea goldies shelter under a coral-decorated overhang at underwater seamount Mount Vema. (Photo: Richard Barnden / Greenpeace)

Of course, there is an environmental cost to their activism and scientific research. The year-long voyage demands four tons of diesel each day, and that’s just for the Arctic Sunrise, one of three vessels participating in the voyage. They do not anchor at Mount Vema due to the sensitivity of the ecosystem but drifting overnight means that they have to turn their engines back on to return to their research site each morning.

The Arctic Sunrise uses the “cleanest diesel, free of the usual amount of sulphur” according to Maack, but their presence is “for the higher good”.

“We have a carbon footprint, but our presence here is for the protection of the oceans and that’s something we need to take into account. Yes, we’re burning fuel, but on the other hand we can show the beauty of the high seas and call for its protection,” he says.

Nzimande says nations across the globe must commit to a robust and legally binding document to protect at least 30% of our oceans.

“This is a significant moment in history. We’re hoping that the accumulation of all our scientific research here and some of the beautiful pictures and documentation we’re going to get from this expedition, will really feed into the United Nations process negotiating for a strong and robust Global Ocean Treaty,” says Nzimande.

“As a species, we’ve caused so much destruction, not only on land but also on our oceans. The damage has been done, some of it is irreversible, but if action is taken immediately there will definitely be positive impacts.” DM

A 10-DAY TASTE OF LIFE AT SEA

Greenpeace is one of the original greenie movements, founded in 1971 with a handful of environmental activists. One of their first missions was stopping a US nuclear weapons test near Alaska. Today the organisation has a presence in 40 countries with thousands of employees and volunteers and has taken on oil conglomerates, destructive fishing vessels and companies tearing up rainforests.

Tristan rock lobster at Mount Vema, 1000 km from the coast of Cape Town. The tristan rock lobster was through to be fished close to extinction. The crustacean and fish population has been able to recover well following a ban on fishing in the area in 2006. (Photo: Greenpeace)

The crew aboard the Greenpeace ship the Arctic Sunrise work on a rotational basis: they have three months on followed by three months off. Seasickness is a real thing, even for experienced crew with “sea legs”. The Arctic Sunrise is a 50m steel ship that accommodates 36 people, and rocks relentlessly. The crew call the vessel “the washing machine” because it constantly moves from side to side. Even on calm days, anything set down on a solid surface is sure to slide, from morning coffee to work tools and laptops.

Each cabin has a bunk bed which two crew members share. Wake-up call is at 7.30 each morning, toilets and showers are cleaned after breakfast and then the crew get to work. In the case of the Mount Vema mission, this meant divers putting on their gear and getting ready to get footage of the seamount and collect kelp samples for the marine biologist onboard. Smaller rigid-hulled inflatable boats (called ribs) have to be lowered to get some of the divers back on board, and crew members often go out on ribs to water-collect samples for DNA testing. After a hard day of work at sea, crew members share a beer or two, watch movies, play darts, or meditate on the deck. Whale spotting is also a popular pastime.

There’s artwork and graffiti all over the ship and a framed newspaper article proudly displays the time the Arctic Sunrise was rammed by a Japanese whaling ship in 2006. Another chunk of memorabilia hangs on the lounge hall from a 70-degree tilt the Sunrise once did which dislodged a container which ripped through some of the cabins, causing serious internal damage to the vessel.

But the ship clearly belongs to activists past and present. Photos of crew members from previous campaigns grace bulkheads in the lounge, where after-work drinks are shared each evening. On the door of the fridge, crew and volunteers who have passed through the passageways have written notes like, “You are superheroes” and “Thank you Greenpeace”.

There’s a real sense of solidarity on board, one that can only be cultivated when almost 40 adults share a small space for months on end. DM

Leila Dougan was on board the Arctic Sunrise as a guest of Greenpeace.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider