“The future is now, it’s just not evenly distributed yet,” says Dr Elsa Sotiriadis, quoting America-Canadian science fiction writer Wiliam Gibson, who is said to have first uttered the phrase in a 1993 interview. Sotiriadis used the quote while speaking at the Øredev developers conference in November 2018.

She is a synthetic biologist, futurist, science fiction writer, biotech venture capitalist and self-described “bio-futurist”. Her field of interest right now is the world of digital biology – from biohacking to exploring how future computer parts won’t be manufactured but biologically grown.

In the tech scene (and on her website), she is also candidly referred to as a cyborg, due to the microchip implant between her left thumb and index finger, which she got live on stage at the 2016 Pioneers Festival held in Vienna. During the event, she demonstrated how she could use the implanted chip to send a pre-programmed tweet by simply swiping her phone over her hand.

She was not the first person to get a chip implant, of course. Kevin Warwick, a British scientist and professor of cybernetics was the first person known to have surgically implanted a silicone chip into his body, back in 1998. The chip used radio frequency identity (RFID) technology and it allowed him to operate various things, such as room lights, locks and lifts.

Back then, he told The Independent:

“The potential for this technology is enormous. It is quite possible for an implant to replace an access or visa card. There is very little danger in losing an implant or having it stolen.”

Almost seven years later, Amal Graafstra, a tech hobbyist at the time, managed to implant a bioglass-encased RFID transporter into his left hand, later followed by a more advanced version. By 2014, he had launched his biohacking company Dangerous Things and created another first, an implant that uses near-field communication (NFC), the same technology that can be used in smartphones today to make payments at speed points or transfer data to a phone in close proximity.

On Friday 13 September 2019, Sotiriadis took to the stage once again, this time at the Gather Festival, a two-day interdisciplinary conference of cutting-edge ideas and innovation held in Sweden, which Maverick Life editor Emilie Gambade attended. This time, she greeted the crowd with a smile and “Hello, Humans!” – setting the tone for a talk that was pro-biohacking, barely touching on the ethics around robotising humans.

The festival wasn’t just for talks: workshops, interactive sessions and a “chipping party” were part of the programme. To get microchipped (an implant injected in the hand), willing participants had to simply dish out 1,495 Swedish krona (about R2,282) and let a young man insert the implant with a syringe into the soft skin between the thumb and the index finger. The procedure was hosted by Swedish microchip company Biohax, and Dsruptive, a Swedish human augmentation design agency.

Sweden has become a bit of a leader in this field and in 2018 more than 4,000 Swedes were microchipped. Sweden’s largest train company, state-owned SJ, allows chipped commuters to use their hands instead of tickets. Some companies in Sweden, Australia and America are giving employees the option to get chipped for entry to the premises, as well as to access their computers or even confidential media.

Although still rather controversial and far from having considerable market penetration, the technology is available for enthusiasts – “It’s just not evenly distributed yet”.

Closer to home, finding a South African company that does human microchipping is tricky.

In 2015, Bushveld Labs popped up in online interviews:

“Our experiments have been aimed at the practical aspects of living with implantables, figuring out how to power implanted devices, and working out ways to integrate implantables with the internet. Some of the future applications that we see implantables being used in include blood glucose monitoring for diabetics, heart attack prediction and emergency alerting, activity monitoring, sensory augmentation, access control, cryptocurrencies and micropayment,” the Bushveld Labs team told arts and culture website 10and5.

Since then, their online presence has died down. The Bushveld Labs website is no longer active and their social media channels have not been updated since 2016. We did manage to briefly chat with Bushveld Labs co-founder Jarryd Bekker, who informed us that the experimentation was carrying on and they were planning on microchipping a friend “in about two weeks’ time”.

At the time of publishing, Bekker had not responded to follow-up questions sent via e-mail, or answered our phone calls.

Whether or not South Africans would be keen to get microchipped is anybody’s guess.

Detractors of the technology range from religious individuals, who see the chip as a fulfilment of a biblical prophecy about the “mark of the beast”, to those who see it as a security nightmare, further adding to concerns about invasion of our privacy.

Microchips have been used since the 1990s in pets, as a way to identify them should they go missing. Pet microchips do not necessarily have a feature through which they can be tracked.

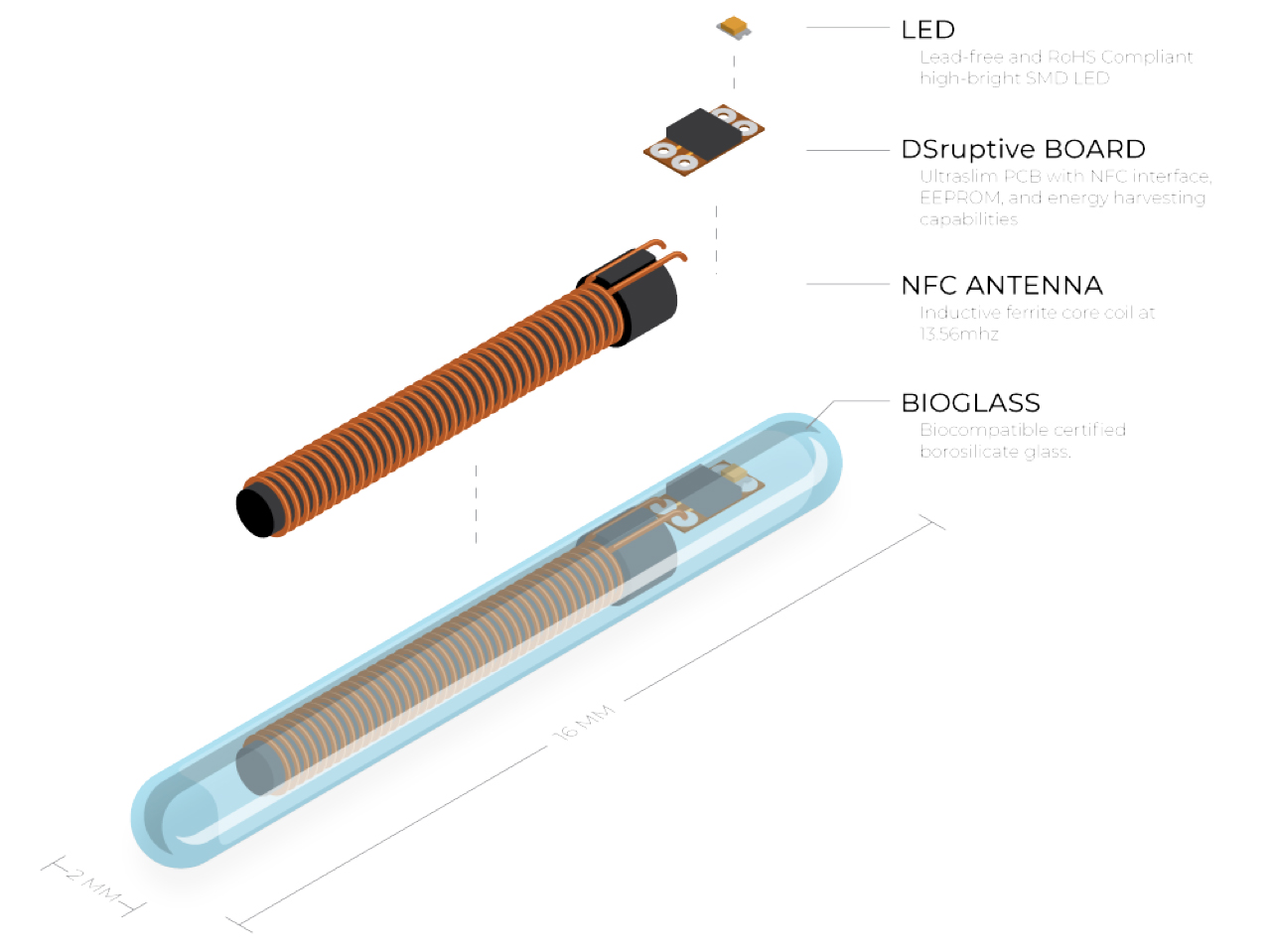

The current wave of human microchips don’t have batteries. They’re the size of a single grain of rice, don’t have of a lot of memory and generally store basic information that can be extracted by other machines in the environment.

MODULAR PLATFORM FOR IMPLANTS SIID (Image from http://dsruptive.com/)

Technically, a person cannot be tracked via a microchip alone, though, if there is a machine that can interact with the microchip, some movements and activities can be documented.

In 2006, Citywatcher.com, then a video surveillance company in the US, started microchipping employees who dealt with their most confidential data, so that they would require the RFID chip in order to access certain data.

In 2018, at another US company, Three Square Market, 50 employees were voluntarily chipped. Their implants allowed them to do things like logging onto computers, buy food and beverages in the company cafeteria and get into the office more smoothly.

The technology is still in its infancy, but implanting technology into the human body is nothing new: we already have pacemaker implants and cochlear implants that have improved many a life. Many of us travel daily with at least two RFID chips using similar technology in close proximity to our bodies: the chip on our bank cards and the NFC chip in our smartphones.

In a best-case scenario, the tech could grow to offer health advantages, from being able to store one’s full health history, to being able to monitor current health status.

Worst-case scenarios range from information theft, to tracking down human beings wherever they may be and hacking their private and personal information.

Big Brother, where art thou? ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider