OP-ED

Do we actually know how well our courts are functioning?

Given its pivotal role in a functioning democracy, the judiciary would do well to rethink its approach to accountability and data. Currently, the statistics it provides are, in a nutshell, meaningless.

The judiciary may well be the most highly regarded arm of the South African state, especially in light of how it stood firm on Constitutional principles during the height of State Capture.

The institution has far-reaching powers, particularly in respect of the legality of executive action, in light of which reasoned disagreement may be expected. Recently, however, the judiciary has come under fire from the EFF as well as a particular faction of the ANC, both of which back the controversial current Public Protector, Busisiwe Mkhwebane. These attacks form part of a baseless attempt to undermine the courts, which have rebuked the Public Protector in a variety of cases she has lost.

We should, however, differentiate between gratuitous or politically motivated attacks on the judiciary, and legitimate efforts that seek to ensure that the institution is held accountable.

In order to hold the judiciary to account, one needs to know whether the judiciary is exercising its powers independently (without fear, favour or prejudice); whether its work is of a qualitatively sound standard (are judgments well-reasoned?), and efficiently executed (how long does a case take to move through the judicial system to finality?).

Here, I focus on the measurement of judicial outcomes (qualitative metric) and processes (quantitative metric). These are metrics without which citizens cannot properly hold the judiciary to account. As the saying goes: “if it matters, measure it.”

It is commendable that on 23 November 2018, the judiciary released its first Judiciary Annual Report for the period 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. According to a press release from the judiciary: “[t]his was a historical event as it was the first time the Judiciary, as an Arm of State, took the lead in accounting for its work, and for the power and authority the State has endowed to it.”

The world over, strong democracies measure judicial performance against various metrics and produce statistics for public scrutiny. These statistics are grouped into meaningful categories and reported on to allow citizens to evaluate the effectiveness of the courts.

The judicial statistics for England and Wales, for example, cover the civil and criminal courts and give detailed figures regarding specific areas of judicial decision-making. Among the numerous reports, for instance, there is a quarterly report focusing on criminal court statistics. The report enjoys “National Statistics status”, signifying that the statistics it contains “meet the highest standards of trustworthiness, quality and public value”. Added to this, the report is accompanied by a “Guide to criminal court statistics” which covers “concepts and definitions… overall statistical publication strategy, revisions, data sources, quality and dissemination, and methodological developments”. Such a guide allows interested citizens to better understand the numbers presented.

What is South Africa’s judiciary measuring and how?

Although the South African judiciary has certainly taken a step in the right direction, it has a long way to go. If one excludes filler images of court buildings, the section on “Court Performance” of the 2017/2018 Judiciary Annual Report 2017/2018 contains roughly five pages of text and tables. This section covers all superior courts in South Africa.

Essentially, there is only one metric by which “court performance” is measured. This measures the total number of cases “finalised” by each of the superior courts within the period covered by the report, namely 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018.

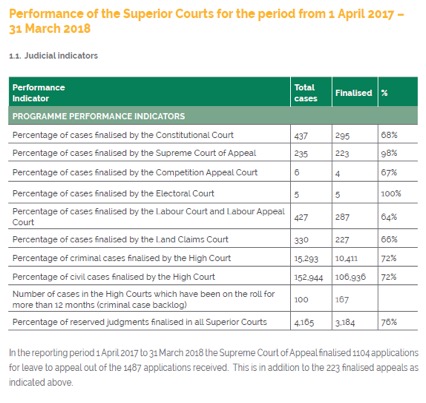

Below is one of the key tables that appears in the report:

No definitions or explanatory notes accompany the table, bar the note about the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) below it.

Many questions arise from this table. Here are some of them:

What does “finalised” mean? According to the table, the Constitutional Court (CC) has 437 cases to “finalise” while the SCA only has 235. We know, however, that the CC hears far fewer cases than the SCA so these numbers are hard to understand. There does not appear to be a like-for-like comparison.

I queried these numbers with the Office of the Chief Justice, the body responsible for compiling the Judiciary Annual Report. It seems each court decides what “finalised” means for that particular court. The SCA had settled on a different definition to the CC: roughly, the SCA, it seems, reports on judgments handed down whereas the Constitutional Court definition appears to include cases that are also dismissed by the court and never heard.

Despite this difference in definition, the numbers figure in the very same table, one above the other, suggesting they are measuring the same thing. (The note below the table on the additional cases the SCA “finalised”, instead of adding clarity, merely raises more questions.) Without the consistent application of the criterion of “finalised” across all the courts, one cannot assess comparative performance. It may be that appeal courts and other courts should be assessed differently, but this would need to be clearly specified.

Furthermore, in order to finalise something, one must begin to do it. When the figures refer to cases being finalised, it is entirely unclear what the baseline of the measurement is. What is the starting point? In other words, if the SCA has 235 cases it needs to “finalise”, how many are there at the beginning of the measurement period (so 1 April 2017) – are there 235 at this point? Or is it a lower number to which further cases are added throughout the measurement period? Also, at what point does a case count as one to be “finalised”? Once it is enrolled? Once the case has been heard?

As the report stands, we do not know what is being measured.

What do these statistics tell us?

There are two points to be made here.

First, since we do not know what is actually being measured, the “statistics” presented tell us little. The report thus cannot do much to enhance accountability.

Second, even if it had succeeded in measuring the total amount of cases that were “finalised” (where “finalised” includes cases that are dismissed and baselines and definitions are given), we would still not be in a position to tell how well the courts are functioning.

This is so for a number of reasons.

First, the report essentially deals with only one single metric. Thus, what it can tell us about judicial performance is necessarily limited.

Second, one cannot infer anything about the quality of “finalised” judgments. The judiciary’s current framework for monitoring “court performance” does not include a qualitative metric. One way to measure this is to measure how many decisions of the High Court are appealed and, of those appealed, how many appeals succeed.

Third, “finalised” covers many different types of cases. A case that is dismissed after a short hearing is not comparable to a complex matter in which a detailed judgment is given after a long trial. Performance needs to take into account the type of case being determined. To lump disparate cases together makes the final number less meaningful. One must distinguish between cases which are (1) withdrawn, (2) dismissed, or (3) heard and in respect of which a judgment is handed down.

Fourth, it would be helpful to measure when cases are finalised in respect of different classes of cases. Are the courts disposing of trial actions as efficiently as they deal with applications, some opposed and others unopposed? Are criminal and civil trials administered with equal efficiency? So, too, complex trial actions should be capable of separate measurement from simple unopposed divorces. Aggregate figures of cases finalised fails to account for the distribution of the classes of cases that a court must determine.

Fifth, the table does not tell us how long it takes for cases to make their way through the judicial system, from application or enrollment to conclusion. Of course, there may be delays and some delays may be due to the litigants and not the court system. However, one should also measure delay and assess what is causing the delay. How much time is taken to obtain a date for a hearing? How much time is taken for the judgment to be handed down? Such information would be very instructive.

What should South Africa’s judiciary be measuring?

The judiciary needs to measure more and do so more clearly for the public to be able to hold it to account and, indeed, for the institution to be able to hold itself to account.

It need not reinvent the wheel. It could simply look to good practice elsewhere in the world. It could, however, also engage with legal stakeholders – judges, court staff, counsel and attorneys – to determine areas of statistical interest that might well be particular to South Africa. The judiciary might also ask civil society organisations involved in the field of accountability about the types of judicial statistics that would serve as good indicators of the health of the judiciary.

Obvious examples of statistics that would be of great interest would be, for example, those relating to

-

The length of time between the application to a court to hear a matter and the enrollment thereof; the enrollment and the hearing or trial; the conclusion of the hearing or trial and the delivery of the judgment;

-

A breakdown of reasons for postponement or delays where there are such (eg the witness fails to appear, no court stenographer present, problems with evidence provided by the police etc); and

-

Appeals and the overturning of judgments.

Statistics relating to the above would need to be presented with great care, and broken down into meaningful detail. As the title of David Spiegelhalter’s book The Art of Statistics suggests, there is an art to selecting, measuring and presenting data from which we aim to derive knowledge.

Given its pivotal role in a functioning democracy, the judiciary would do well to rethink its approach to accountability and data.

Meaningful data around the judiciary would enable us to know how our courts are actually faring. Currently, we are rather in the dark. It would also allow the institution to determine areas in need of improvement. Finally, it would allow the public to hold this institution, which enjoys vast powers conferred upon it by the Constitution, to account. DM

Cecelia Kok is Head of Research and Advocacy Projects, South Africa, at the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider