Video filmed and edited by Malibongwe Tyilo.

When exploring the survey – the largest retrospective of William Kentridge’s work to ever be presented on the continent – Why Should I Hesitate: Sculpture opening at the Norval Foundation today, and Why Should I Hesitate: Putting Drawings to Work opening at the Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA) on the 25th of August, one is soon absorbed by the sheer abundance of work.

It is everywhere, capturing one’s attention: in front of one’s eyes, entering one’s ears, floating over one’s head, towering over one’s path. Fragments of the world and our history filling the museum, gently pushing the visitor into a travel machine which wanders into forty years of the artist’s extraordinary career.

It never feels overpowering, though; the genius of the artworks, the brilliance of the survey’s agency is to leave the visitor with unanswered riddles – to leave it to us to breathe the final meaning into it.

“The exhibition is called why should I hesitate, and I do hesitate to try to think what the name means. It’s at the edge of meaning. I’m interested in riddles that don’t have a solution; does it mean I should hesitate because I’m uncertain, otherwise it says why should I hesitate I know what I’m doing; I’m not going to hesitate, a rhetorical question so the ambiguity of that and the fact that there is no question mark is about saying to the audience, ‘Here is a set of riddles for you to look at and understand some but not all of’,” says Kentridge.

Kaboom installation, 1997, by William Kentridge (Image courtesy of the Zeitz MOCAA)

The wealth of work presented simultaneously at the Zeitz MOCAA and at the Norval Foundation is only a small part of Kentridge’s oeuvre. The artist says that the exhibited works make up only about two percent of all the drawings he’s made and half of the video work he produced – and, in a murmur, adds that he wished he could have included a ‘Room of Failures’ to also show all the work that has never left his studio.

But the physical work is not the only evidence of Kentridge’s prolific interpretation of history; words – fragments, riddles, revolutionary, colonialism, ‘idles’, communism, ambiguity – bounce from one wall to another, leading the visitor like Hop-o’-My-Thumb’s pebbles on a path to a cross-continental voyage.

Studio, William Kentridge (Image courtesy of the Zeitz MOCAA)

“I think there’s an intersection in the work: it’s broadly chronological. We start with the room of early drawings and even student work and we end with more recent video installations. Not strictly chronological because of the shape of the rooms, some projects had to be in some rooms, but broadly. There’s an overabundance of different images and out of these fragments I selected, and from this one makes a provisional understanding of the world or description of the world,” the artist explains.

Practice and repetition are also evident in Kentridge’s work; he cites Gabriel Garcia Marquez, who once said “The duty of a writer – the revolutionary duty, if you like – is simply to write well,” to explain his role as an artist: “The duty of the artist is to be at his studio and work”.

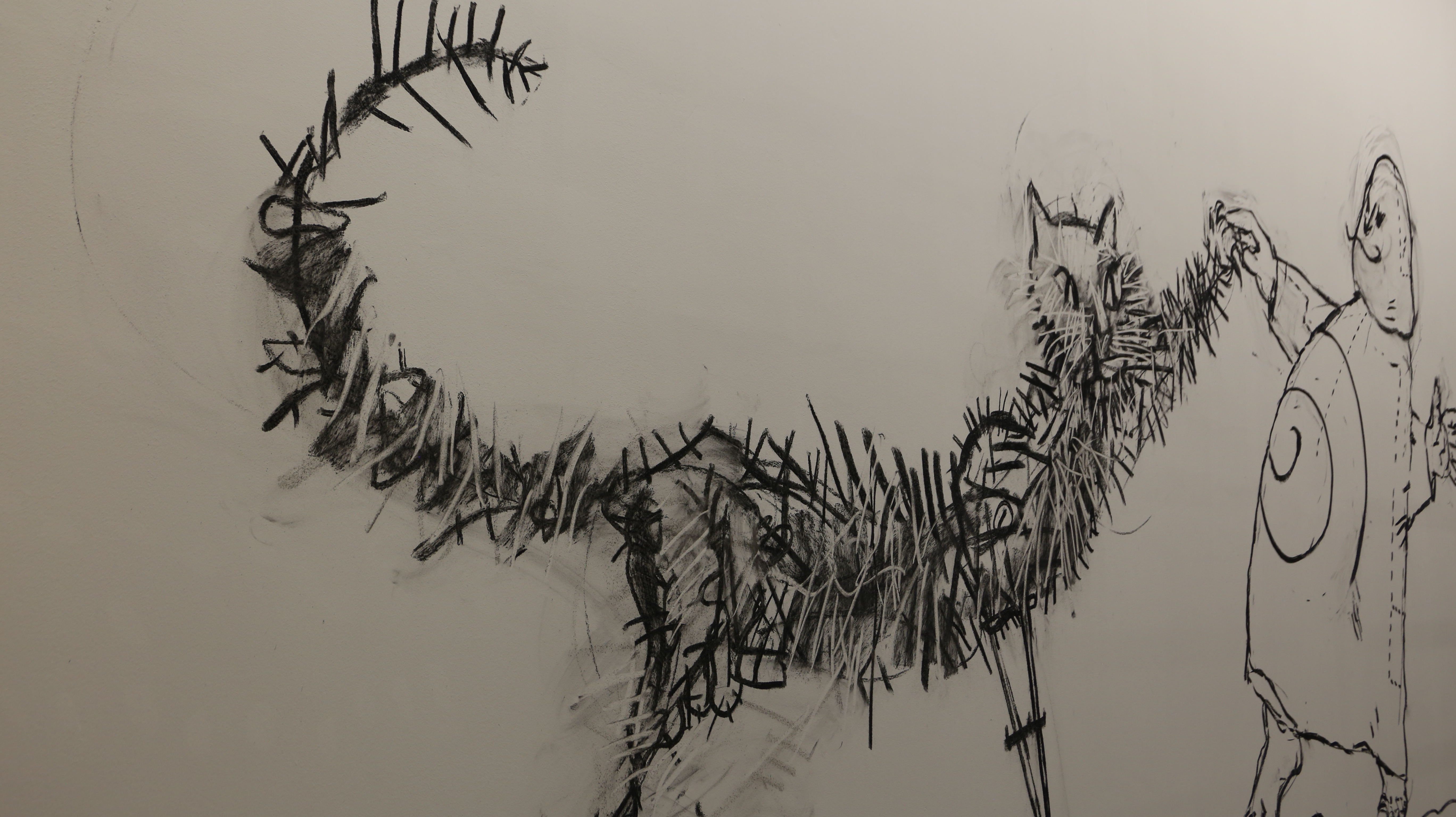

Nine days ahead of the opening, the artist’s hand is spontaneously drawing Ubu tells the truth on one of the museum’s walls – using a baton of charcoal, removing it with a piece of white cloth, drawing it again, removing it once more, his hand darker with every move. The hand is confident, the body steps away and hesitates; the silent dance continues until eventually doubt disappears and the suddenly alive drawing takes over the space, Ubu’s belly a reminder of the 1896 Alfred Jarry’s comic – and its warning ‘about bourgeois tendency for avarice, power grab and complacency with newly gained power and wealth.’

‘Ubu tells the truth’ by William Kentridge (Image courtesy of the Zeitz MOCAA)

“There’re sections which are quite demonstrative of process, where you see a preliminary drawing and a finished print, or you see a video that explains how the woodcuts are made, or how the tapestry is done. So, it’s to try to show the agency in making, and the possibility of agency.

“It’s not like any of the techniques are so full of magic or strangeness, and it’s a way to give encouragement or energy to the people looking at it, to say this is an activity, a physical activity of the hands not the body, through which one can make some sense of the world”.

Certainly, William Kentridge’s work is about processes and production. Theatre and theatre staging infuse the show and so do the collaborations. The teams that helped put both exhibitions together read like the cast of a movie super-production: from the curators, Azu Nwagbogu and Tammy Langtry at Zeitz MOCAA and Karel Nel, Owen Martin, Talia Naicker, Vicky Lekone at Norval Foundation to the design and production teams and William Kentridge studio, many have joined behind-the-scenes to help set the stage for the extensive exhibition.

“When conceptualising this exhibition, we wanted to do more than simply attempt to condense many of Kentridge’s projects from his illustrious career into one space. It was vital to unpack Kentridge and reveal more of his processes and how two-dimensional forms assume life. We also wanted to offer a sort of ‘backstage’ view of the artist on his journeys and his experimentations, and sometimes at his most uncertain and vulnerable,” says Nwagbogu.

Tapestries by William Kentridge (Image courtesy of the Zeitz MOCAA)

“There’s historical material in the exhibition, a lot… There’s a lot about colonialism, about the Italian war in Ethiopia, about the African experience in the first world war which was really about colonialism, about the new colonialism of China and its relationship to Africa, but there are usually historical reflexions.

“I’m not a news commentator on what’s happening in the moment, only in retrospect can you see the connexion of the works that are drawn to the historical moments in which they were made”, says Kentridge.

Both shows also present a conversation, not only between the artworks, their size, texture, reference and meaning, but also between two art institutions – and the power of coming together to create a survey that offers context and engagement to the artist’s extensive creative career.

“It’s always a mixture. It’s a mixture of what you see in front you, the film, the drawing, or the sculpture, and what you project onto it, what are the associations that you get when you see the artwork. So, the hope is that there’s enough of an electricity between what the work brings and what you project onto it to make for an exciting journey”. ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider