The only public sign these days of the presence of the artist and teacher Bill Ainslie is the rare emergence of single paintings on auction. He died in a car accident 30 years ago this month, leaving behind a body of work, memories of his much-loved Art Foundation and the respect expressed by so many different people whenever his name crops up. He did not live to witness the release of Nelson Mandela from prison, nor was he there to participate in the democratic election of 1994. Dying as he did at the age of 55, there is a good reason to believe he had a great deal more to offer than all that he achieved.

Ainslie made it possible for others to feel and experience that there were better ways to live than what South Africans had endured for most of the 20th century. In exercising that influence, Ainslie was a practical visionary who spoke through his paintings, his teaching and the creative environments which he and his wife, Fieke, assembled. Their lifetime commitment to work on behalf of black artists is universally respected.

Ainslie broke into the harsh art world of Johannesburg in 1963 after a stint of teaching art students at Cyrene Mission, a short way outside Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. By then, he had found the confidence to paint his emphatic black figures in such ways as to challenge at root, the long tradition of pictures by early European travellers and white South African artists of black subjects as quaint, exotic, or pitiful beings, objects of sentiment and curiosity.

Ainslie’s figures were located in mundane and everyday situations, such as mothers with their tiny children; children at play, watching and doing chores; men waiting for employment, and women walking with bundles of washing on their heads.

Instead of objectifying people from whom he was inevitably distanced, Ainslie’s paintings depicted real situations so as to evoke the normal feelings and concerns felt by people. By elevating ordinary people into the normality denied them by attitudes of dominance, Ainslie’s figures expressed common qualities such as care, love, delight, absorption and watchfulness. This was a bold statement to make then.

Here is a description by Lionel Abrahams of one of Ainslie’s typical figurative works:

“The first [work] was a huge canvas by Bill Ainslie, one of his mother-and-child compositions, the figures (as in all his work) African but otherwise uncharacterised, supra-personal embodiments, marvellously corporeal, of their functions and feelings – mother a giantised spirit of protectiveness, the child a minuscule emblem of dependence and instinctual trust, the whole an affectingly forceful illustration of tenderness.”

Ainslie did not elide the harsh conditions under which urban and rural black people had to live. In the case, for example, of the painting of a child illustrated below, it is perfectly clear that her context is one of tough circumstances which include poverty and violence. Notice her watchfulness, her confrontation with who is in front of her, the protective manner in which she holds the doll and a stance that suggests courage in the face of the uncertain. In actual fact, she is looking hard at you, the onlooker. What is your next move?

This child has seen and knows much, and most of it demands watchful readiness. In no manner can this depiction of childhood be read as sentimental or emotionally exploitative. She represents a rich, varied and complex set of circumstances, painted with skilful austerity.

Child with Doll. c. 1964. Oil on board. 60 x 90cm.

These figurative paintings were well-received by the public, especially among liberal circles which, a short time later, received with acclaim the poetry of Oswald Mbuyiseni Mtshali whose Sounds of a Cowhide Drum sold 10,000 copies in just over a year. At that time, thoughtful white South Africans were making tentative efforts to link with their black compatriots without confronting the bases of their situation.

When Ainslie held solo exhibitions in Johannesburg in 1964 and 1966, his work was highly regarded for its thematic and painterly qualities, meaning that he was taken seriously as a new artistic voice in the city. He and Dumile Feni established a close professional relationship in the late 1960s, working together for two years and holding separate shows of their work. This association meant that Ainslie was drawn beyond the city suburbs into the turmoil of the townships and their leading figures who visited from Soweto such as Peter Magubane, Winnie Mandela and Dumile’s good friend from Alexandra, Mongane Wally Serote. Hindsight allows us to perceive the creative and political intensities which combinations of people such as these generated for each other. This is what Serote said of the atmosphere he found in Ainslie’s home and studio in 1968:

“Many young men and women, black and white, gathered around this space and place, like bees around something sweet…There was the smell of acrylic and oil paint, and of good food, of perfume and life lived…Bill and Dumile, who were the honey, gave the place a dreamy feel as if there was something big about to happen.”

The memory of that honey-odour of creativity in Ainslie’s establishment led to the understanding in the 1980s by Serote and his close associates in the ANC in exile, of the importance of arts centres for people who were confined in multiple ways by their situations in townships and rural villages. They too needed a whiff of creative possibilities and so Ainslie’s teaching operations, latterly through the Johannesburg Art Foundation, became a model for ANC planners in exile (as well as black artists in New York) of the value of establishing centres to which a wide spectrum of people should have access.

Before that endorsement of what he was doing, Ainslie played a major role in the formation and establishment of the Federated Union of Black Artists (Fuba) and other city and township-located centres, and thereafter, with Joe Manana he led the setting-up of the Alexandra Arts Centre. This was followed by the initiative of David Koloane and Ainslie in founding the annual Thupelo Artists’ Workshops from 1985 onwards, a project which now, thanks to the support of Robert Loder, has offshoots in more than 30 African countries.

At the outset, the tone set for the Art Foundation workshop environment was crucial. No authoritarianism, no pressure from sources outside such as qualifications, enormous tact and patience in letting participants discover and experiment and work in their own ways, trust and respect for the innate creativity of each person, the recognition together of possibilities and opportunities.

With Joseph Beuys, Ainslie regarded workshops as forms of social art in themselves where alternative ways could be discovered, and untried areas could be explored. The practice was augmented with seminars, discussion groups, poetry readings, music, lectures, slide shows and the influence of diverse visitors.

David Koloane observed that Ainslie “was a committed teacher and very unique in that he had time for everybody. You know he had the patience, he had the time, he never gave up on a student or gave up on anybody. He would actually make you realise that what you thought were mistakes were actually your strong points so that in a way he changed the perception that there was something wrong [with what you had done].”

Ainslie himself said this:

“I started teaching privately and then it became a workshop… when I joined others who found that they didn’t belong. I love working in this situation and I consider it a ‘blessing’. The free, vitalising and thorough interchange that can take place between people who have freely chosen to discover for themselves what they really most need in their work is a blessing…Everybody freely chooses to discover for themselves what they really most need in their lives, and in this they encourage others to do the same. This is the chief aim of the work.”

All this occurred under the truculent and deeply suspicious attention of the Security Police, who invaded, watched, tapped phones and tampered with mail in their repeated searches for incriminating activities. Under interrogation, Serote found that what perturbed these minions of apartheid most was the idea that black people were offered a context in which to discuss art, poetry and other creative activities, and that those opportunities were sufficient inducement to bring people together regardless of colour, age and disposition, to labour continuously and hard at producing work of the highest calibre. The banning in 1977 of a large number of cultural organisations, many inspired by Black Consciousness, underscores how seriously the state regarded the pursuit of culture outside of its aegis.

With the enforced departure of Dumile, and his meeting with Douglas Portway, a South African artist who lived abroad, Ainslie sought new direction for his paintings in answer to the challenge of being an artist in a systemically and structurally unjust society.

He came to realise that he needed to strike out beyond the figurative to produce art which was African and did not seek authenticity by including references to Africa. He began to explore the possibilities of colour-field and abstract paintings which referred to recent developments in the US and older forms of abstraction from Africa as well as aspects of contemporary Eastern art.

It took him more than 10 years, including time in St Ives in the proximity of Portway, as well as building his teaching operation and finding a more permanent base for his work and family, for him to make the abstract paintings which characterise his final decade of work. Once in a stable venue and as director of the Art Foundation, Ainslie gave full rein to his teaching and painting while sustaining his involvements in many levels of community activity.

As was said by John Peffer in his Art at the End of Apartheid (2009):

“Despite all his rhetoric about painting outside of ideology, his commitment to working in a non-racial manner and the company he kept, garnered for Ainslie the most profound respect among those who would later go onto leadership positions in the African National Congress.”

Ainslie was certain in his mind about the distinction between the work of artists and the making of protest art. He wrote:

“The greatest quality required by the protest artist is courage, concern and the ability to strike on a way of presenting this in a clear manner. The greatest quality required by an artist is the determination to adhere to the constraints and illuminations of the inner eye – frequently against the pressures to conform to a more popular and public view of things.”

For all their remarkable achievements in paint, his two solo shows in the 1980s were not commercially successful, but these arguably included some of the most achieved and beautiful paintings done in South Africa in the 20th century. For example, Gatooma c.1986:

Gatooma c. 1986. Acrylic on canvas. 1.68m x 1.89m.

Activists in the struggle for liberation rarely had the cultural and artistic experience to perceive how relevant these abstract works were for their time and how significant they are today. Many people find wholly non-figurative and abstract art merely decorative or without meaning. For such, when art does not have a “message” or a “lesson”, it is regarded as self-indulgent. For example, it took one writer and thinker and political activist considerable time to understand the force and significance of Ainslie’s abstract paintings.

Serote quarrelled inconclusively with Ainslie in 1987 over his commitment to abstraction, but when Serote stayed for a time after 2000 in the Ainslie home, he was surrounded by big abstracts on every wall. In the early mornings, when he rose to write poetry, he noticed that with changes in the light, how the paintings began an interplay of colour and texture within themselves and among each other as subtle responses to the light. It was then that he began to understand the force and validity of abstract art in its poetic interplay with shifting multidimensionality and how basic to a liberated mind and heart such awareness is.

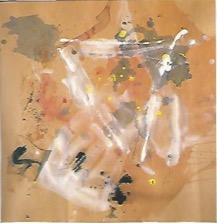

When Ainslie attended the second Pachipamwe (Thupelo) Workshop in 1989 a short distance outside Bulawayo, where he had taught nearly 30 years before, he was at the beginning of a new era, an era which was probably going to be more about his own painting than anything else. His energy and the sustained rapidity of completing and beginning paintings at the workshop, astonished his friends and fellow artists. In two weeks, he produced six completed canvases and 10 works on paper, all of them found in his car after the fatal accident. The Pachipamwe Series, as they are now known, have been snapped up by collectors from many parts of the world and few remain in South Africa. Here is a single example:

Pachipamwe No.8 Acrylic on paper 69.5 x 69cm.

Though auction houses in SA are becoming keen to chase up the monetary value of his work, it is at other levels of cultural awareness and enrichment of this country’s artistic history that Ainslie’s contributions, which are much greater than is currently realised, should now be explored. This could begin to happen if institutions such as the Wits Art Museum, which recently held a remarkably fine exhibition of the work of Albert Adams, were able to consider mounting, if not a retrospective exhibition, at least a representative showing of the range and extent of Ainslie’s art, with an apposite catalogue. DM

Michael Gardiner worked in education policy and has contributed to discussions of South African literature. He is compiling a full-scale memoir of his friend Bill Ainslie and his time in Johannesburg.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider