‘THE EAGLE HAS LANDED’

Fly me to the Moon and let me play among the stars…

Fifty years ago, on 20 July 1969, the Earth’s population waited with bated breath for word that the first men on the Moon had landed there safely – and then again as they departed their lunar orbit to return to Earth. It was a massive technological, scientific, and human feat. But the age of exploration it was supposed to herald for humans has never really materialised. What did it all mean in the end?

There is that awesome moment in the final scene of the lark of a science fiction/romantic comedy film, Space Cowboys. It stars James Garner, Clint Eastwood, Donald Sutherland, and Tommy Lee Jones as four old geezer astronauts suddenly called back into emergency service, with James Cromwell as a Nasa heavyweight boss, and Marcia Gay Harden as the mission’s ground-based flight surgeon and Sutherland’s romantic interest. Go watch it if you haven’t seen it.

In the film’s final moments, Jones’ character is left marooned on the Moon, after helping save the Earth from a horrific nuclear catastrophe. The camera slowly zooms on to the sphere of the full Moon, then, closer and closer, as the lunar topography resolves in greater and greater detail; and then, finally, the camera comes to show a space-suited, solitary astronaut reclining among the rocks of the lunar surface. Inevitably, the soundtrack wells up with the sounds of Frank Sinatra crooning one of his trademark hits, Fly Me to the Moon, in that great arrangement by Nelson Riddle. What else could the soundtrack for a film like this have been, other than Ole Blue Eyes’ voice?

An image on an old television set of when the Lunar Module landed on the moon on 20 July 1969. The old TV is inside Mission Control room at the NASA Center Houston, Texas. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Larry W Smith)

There are innumerable musical odes to the mystery, power, and impact of Earth’s nearest astronomical companion, as people throughout history have been tempted to gaze at it in wonder. In more recent times, a shortlist for starters would have to include Dean Martin singing That’s Amore – “When the Moon’s in the sky like a big pizza pie, that’s amore” – as well as perennial favourites such as Blue Moon and Moon River, Mozart’s Queen of the Night (Der Hölle Rache) aria from The Magic Flute, Dvorak’s Song to the Moon from the opera, Rusalka, (listen to Anna Netrebko sing this), Kurt Weill’s Moon of Alabama from The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahogany, a portion of Gustav Mahler’s Song of the Earth, Der Abschied (The Farewell), as well as those instantly recognisable piano pieces – Debussy’s Clair de Lune and Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata.

And even from among the Gilbert and Sullivan repertoire there is that lush aria about the duality of Sun and the Moon, The Sun Whose Rays, from The Mikado (listen to Lesley Garrett sing this one). Then, of course, there is the local classic standard, Back of the Moon, from King Kong, by Todd Matshikiza, and pop/rock tunes like Bad Moon Rising by Credence Clearwater Revival and Moonshadow by Cat Stevens, and even Michael Jackson’s idiosyncratic “Moonwalk” dance move. Moon songs are about water sprites, love, shadows, longing, and mystery – and the reaching deep back into distant, far-off memories.

Of course, pretty much every society on Earth has incorporated the Moon into its mythology and religion (and thus its poetry and prayer), from the beginning of history. Maybe even before there was history, back to when the earliest humans tilted their heads upwards to puzzle at the night sky. While the Sun has always inspired awe for its obvious life-giving properties (and fear when a solar eclipse swallowed it up), the Moon has had a separate spiritual presence – often positioned in opposition to the Sun.

But, unlike almost everything else in the firmament, the Moon remarkably changed its shape every month, regularly disappearing and then returning to its previous fullness, as it cast its cold glow on to the Earth. There was an ancient belief that the influence of the Moon’s rays led to insanity from exposure to them, hence the very word, lunatic. Explanations of the influence of the Moon on the Earth’s watery tides and the even more confounding connection between a woman’s monthly cycle and the Moon would take more modern science to explore.

Many societies have wrestled with reconciling the similar but not completely overlapping cycles of the Sun’s annual circuit (obviously we know now that it is the Earth that orbits around the Sun) with that recurrent monthly lunar cycle. The challenge for the early calendar makers was that the Moon’s cycle is 28 days-plus in duration from new Moon to new Moon.

Accordingly, 12 of those lunar months equal rather fewer than 365 days (but more than that if one uses 13 months) to mesh with the number of days from winter solstice to winter solstice. While such a discrepancy doesn’t much bother us now, what with fewer and fewer people engaged in traditional agriculture and who are thus dependent on counting lunar months, by contrast, in the ancient world, the accurate measurement and tabulation of those cycles was critical for regulating planting and harvesting times, as well as for the fixing of holidays and feast days.

We see the remnants of this in many religious traditions, such as the ancient Jewish calendar, still in use, that inserts an extra month into the yearly calendar, in seven out of every 19 years, in order to keep the holidays in their appropriate seasons, or with a roughly similar system used by various Christian churches to keep their Easters at roughly the same time of the year. (At least in the northern hemisphere, where this question first appeared, it would make little sense to have a holiday celebrating rebirth occurring in the depths of winter, or smack in the midst of the summer.)

A man looks at one of the original space suits on display at the NASA Center, Houston, Texas. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Larry W Smith)

Societies following the traditional Chinese calendar system, meanwhile, also use another complex reconciliation, so that their Lunar New Year remains in the early part of the now-globally standard Western calendar. And children get to eat their traditional moon cakes associated with that Lunar New Year. Meanwhile, Islam addresses this challenge a little differently, basically by using the lunar cycle for its holidays and the fasting month moves and its holidays move through the year, every year, until they return to their original spot at the point of the cycle from whence they started.

The Moon has triggered a vast literature as well – from the famous children’s go-to-sleep book, Goodnight Moon (now set to music by this writer’s own musician daughter and soon to be released as a recording) to long shelves of science fiction and fantasy, basically beginning (although astronomer Johannes Kepler did pen a short tale back in the 16th century on a bird-powered voyage to the Moon) with Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon (and the film adaptations that came from it), and then on to Arthur C Clarke’s short story, The Sentinel, that eventually became Stanley Kubrick’s classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Beyond those, there are dozens and dozens of other films, novels, novellas, and short stories featuring the Moon.

As a pre-teen, this writer was totally enthralled with astronomy and had built a small telescope suitable for backyard astronomy, just as human space flight was about to take off. Pointing this reflecting telescope with its three-inch mirror at the Moon, I was probably filled with as much wonder as Galileo back when he first looked at the sphere to discover that despite hallowed doctrine, the Moon was not a smooth, perfect surface but, instead, had mountains, craters, and large dark plains, dubbed “mare”, under the mistaken notion they were seas like Earth’s.

In 1961, despite the presumption of US technological and scientific leadership, the world was shocked to hear the Soviet Union had successfully placed a man – Yuri Gagarin – into Earth orbit and returned him safely. Out of this near-existential blow to US pride, coupled with the military disaster of the US-supported invasion of the Bay of Pigs by Cuban emigres, the new US president, John Kennedy, committed his nation to landing a man on the surface of the Moon by the end of the decade. In his speech in Texas at the newly-constructed Nasa control facility, once the US had successfully placed an astronaut into Earth orbit, Kennedy had said:

“We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people. For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of pre-eminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theatre of war. I do not say that we should or will go unprotected against the hostile misuse of space any more than we go unprotected against the hostile use of land or sea, but I do say that space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours.

“There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful co-operation may never come again. But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas? [This was a hot collegiate football rivalry at the time.]

“We choose to go to the Moon! We choose to go to the Moon… We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.”

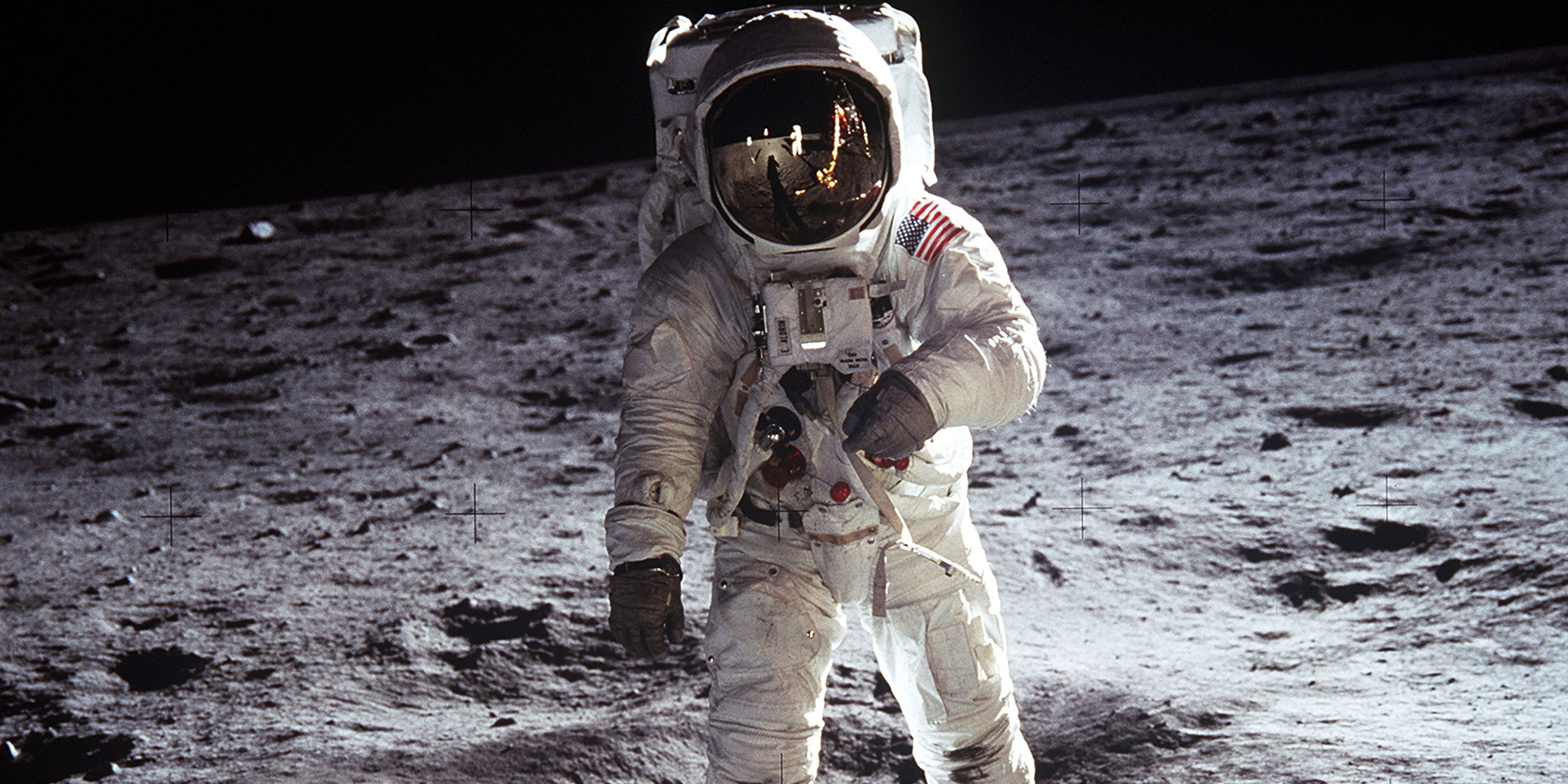

US Astronaut Buzz Aldrin, walking on the Moon July 20 1969. Taken during the first Lunar landing of the Apollo 11 space mission by NASA. (Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

By the time the US space programme had spun through the initial Mercury and Gemini launches and then embarked on the Apollo series of rockets and spacecraft (the two-man lunar module, together with the service and command modules for the entire three-man crew), according to Robert Stone and Alan Andres, in their newly published book, Chasing the Moon: “The American effort to get to the moon was the largest peacetime government initiative in the nation’s history. At its peak in the mid-1960s, nearly 2% of the American workforce was engaged in the effort to some degree. It employed more than 400,000 individuals, most of them working for 20,000 different private companies and 200 universities.”

By this point, overwhelmed by the full-bore application of US science and technology, the Soviet Union had brushed off the very idea that there had even been a space race with the Moon at the end of it as the big prize.

Before Apollo 11, the mission designated to reach and – hopefully – land on the Moon, Nasa had sent several somewhat less ambitious flights of Apollo craft, to circle the Earth and return, to carry out the complex docking and undocking procedures with the lunar lander as test runs, and in one memorable moment, the crew of Apollo 8 had circled the Moon and photographed the astonishing Earthrise over the lifeless lunar surface, before returning to Earth. (I am, in fact, typing these words with that revolutionary image as my iPad screensaver.)

This image, allowing anyone to viscerally understand the fragile life-raft inhabited by all of humanity, all the plants, all the animals, bugs, fish and everything else – helped give a huge kick to the still-nascent global environmental movement – with the sharp understanding there was no Plan-B planet conveniently to hand. The astronauts on Apollo 8 nailed down the impact of their journey with a Christmas Eve reading of the first verses of the Book of Genesis, broadcast live back to Earth.

Apollo 11 left Earth on 16 July 1969 and arrived at the surface of the Moon four days later, at the spot newly-designated as Tranquility Base, whereupon they signalled all was well, with the lunar lander crew telling a waiting Earth, “The Eagle has landed.” (For those who want to listen to a web site that provides every single bit of communication that transpired during this voyage, click here. Also, watch the CBS News special commemorative programming on the launch at this site.

Unspoken to the world at large, until years later, was the fact the lunar module was within a minute of running out of fuel on its approach to the surface, sparking fears that the landing would have to be aborted at the very last second, lest disaster happen. One recent discovery among the President Richard Nixon papers is a draft for the terrible message he would have been forced to deliver, in the event the lunar craft crashed or, worse, if equipment failure had doomed the crew to cold, lonely deaths on the Moon, once their oxygen supply ran out.

File photo of NASA astronaut Conrad Jr. standing with the U.S. flag on the lunar surface

In the end, of course, everything worked out. The Eagle did land, and then, the next day, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin came out the lunar module to dance on the lunar surface, take pictures and collect rock samples, after Armstrong had said,” One small step for man; one giant leap for mankind.” Thereafter, the grammar Nazis insisted he had fumbled his lines of the historic moment, even as Armstrong insisted there was an “a” between “for” and “man”, even if the microphones, recordings and ground crew hadn’t heard it. Well, okay…

The Apollo Programme followed with further flights, including that of Apollo 13, the one with the explosion of the cryogenic fuel cell fluid tank that very nearly killed its three-man crew. Despite the grand idea that lunar exploration was ultimately for scientific purposes, it was not until Harrison Schmitt flew on Apollo 17 that a real, honest-to-Pete, qualified geologist was on the Moon’s surface. Everybody else who reached the surface until then was basically a pilot or engineer first, and a crash-course trained lunar scientist second.

Despite the heavy engineering bias, hundreds of kilograms of Moon rocks were brought back to Earth by the Apollo missions, and scientists around the planet continue to work with them, even now. Along the way, seismic stations and other instruments were set up to report back to Earth. The lunar science from the Apollo programme did help confirm a growing body of knowledge that pointed to the Moon having been formed from ejecta from the crust of the primordial Earth, following a collision with another planetoid, eons ago – thereby explaining the Moon’s lack of an iron-nickel core such as Earth’s, and thus the lack of any strong electromagnetic shield around the Moon, or any tectonic action.

But by the time of Apollo 17, a growing budgetary squeeze on the federal government due to the cost of the Vietnam War meant the final Apollo flight, #18, was summarily cancelled and no one (from Earth at least) has returned to the satellite since. In the years that have followed Apollo 11, unmanned exploration technology has become increasingly sophisticated, leading budget hawks as well as some scientists to ask why a new manned lunar programme is even necessary.

Some argue the next space jump should logically be to Mars where there may be a chance extraterrestrial life exists (at least some hardy, lichen-like things), or where a real human colony could even be established. Yet others argue the money for manned space travel needs to be spent on more urgent earthly needs – from poverty abatement to preserving the planet’s environment before human ingenuity destroys it – rather than further high-cost jaunts to drive around in Moon buggies, collecting rocks.

Those of us who had consumed science fiction, astronomy books, built telescopes, or who had simply watched 2001 multiple times were certain that a half-century after Armstrong and Aldrin’s epic voyage, there would be a thriving lunar colony, one that was gearing up for extensive telescopic explorations of deep space, given the veritable lack of a lunar atmosphere to obscure things. Or, perhaps, the lunar colony would be the marshalling point for the next step into space. But no one believed, a half-century ago, that the population of the Moon would now consist of some radiation sensors, some miscellaneous mirrors, and a range of seismographs.

The plaque on the side of that Apollo 11 lunar lander that remained on the surface once the lunar crew module departed to reunite with the command module, reads, “We came in peace for all mankind.”

It now stands a lonely watch until a new generation of Earthlings may return. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider