The recent decision by the president of Botswana, Mokgweetsi Masisi, to lift the ban on trophy hunting has sparked an international outcry. Individuals, organisations, and at least one travel agent have suggested a boycott of Botswana’s wildlife tourism industry in a bid to force the president to rethink his decision.

Considering that this decision was made after extensive consultations with rural people and local stakeholders, it is extremely unlikely the boycott calls will change anything in Botswana. Instead, the boycott sends at least five clear messages to Botswana and its neighbouring African countries, most of which are probably not intended.

1. Banning trophy hunting is a risky strategy

This message is especially clear to Botswana’s neighbours – South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Zambia – all of which still allow trophy hunting. Although there are occasional hunting-related controversies in all countries, there are no outright calls to boycott their tourism industries. The travel agent called Luxtripper exemplifies this hypocrisy as it now refuses to book trips to Botswana, but still sells holidays to its hunting neighbours.

The leaders of these countries must have taken note of this – if you do not want undue pressure on your tourism industries, never ban trophy hunting. If you do, even as a temporary measure (as was promised in Botswana during the 2013 meetings before the ban), then there will be hell to pay if you ever revert to your former pro-hunting policy. While a decision to ban hunting may be fêted internationally in the short-term, it is a risky long-term strategy.

2. International photographic tourism is a fickle friend

If the photographic industry is substantially weakened by these misguided calls for a boycott, then it will effectively force people in Botswana to usher in the trophy hunters as quickly as possible. Photo-tourism and hunting are the two main alternatives for using wildlife to generate income in rural Africa outside national parks. If photo-tourism is weakened, these safari companies will no longer have the buying power to operate in their concessions, which opens the door wide for hunting operators.

Since the hunting ban in Botswana, a number of former hunting operators were forced to switch to photo-tourism. Similarly, community organisations had to shift from hunting partners to photographic partners. If the photographic business goes well for them, they will not need to switch back to hunting. If their photographic clients all cancel their trips in protest, however, then hunting clients will soon be a better prospect.

3. Elephant conservation does not actually matter

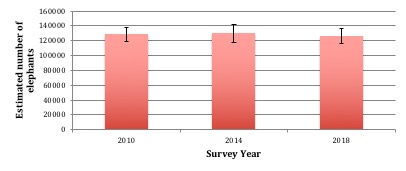

It is an incontrovertible fact that there are more elephants in Botswana than any other country in Africa. Going purely on aerial survey results published by Elephants Without Borders, one can see that the elephant population in Botswana was doing perfectly well when hunting was still allowed. Despite the recent increase in poaching incidents (occurring during the hunting ban period), Botswana’s elephant population is still doing well (see graph below). While numbers appear to have remained stable, the African Elephant Status Report reveals they have expanded their former range towards the south – right into the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. This expansion is actually a result of human activities, as there are now pumped waterholes in areas that used to be too dry for elephants to occupy.

Graph showing the elephant populations estimated by Elephants Without Borders following aerial surveys done before the ban (2010), just after the ban was enacted (2014), and before the ban was lifted (2018). The error bars show the minimum and maximum estimates for each year.

Considering the widespread elephant poaching throughout Africa and the high levels of human-elephant conflict in Botswana, the country deserves an award for its sterling elephant conservation efforts. The last three decades have seen a substantial increase in elephant numbers. Unfortunately, the policies of the last few years that have won so much international acclaim have, if anything, allowed poaching to raise its ugly head in Botswana once more.

Elephants Without Borders reported in 2014 (after many years of trophy hunting) that elephant poaching rates were minimal; in 2018 (after four years of no hunting) they reported substantial levels of elephant poaching. This national poaching increase comes at a time when elephant poaching is declining elsewhere in Africa, possibly due to an economic downturn in China.

Clearly, policy change is needed. But the president who is willing to make this change is being castigated. The boycott message is quite simple: it does not actually matter how well you have conserved elephants in the past or if your current decisions may reduce poaching in future – if you do not make us feel happy we will hurt you.

4. Elephant lives matter more than African lives

One of the reasons that people in Botswana are becoming more vocal about elephants is a recent increase in the number of people killed by these “gentle” giants. Some villagers even live under an elephant-enforced curfew because residents are afraid of encountering elephants at night. A combination of fear and the frequent destruction of their crops resulted in an understandable outcry. The president is merely responding to widespread calls to “do something” about the problem, which is quite normal in democratically-ruled countries.

The international responses to Botswana’s decision reveal a frightening callousness among the former “friends” of the country from the anti-hunting lobby. There is a usual, glib statement about human-elephant conflict being a problem followed by a diatribe against the policy change that was demanded by the people at the sharp end of this conflict.

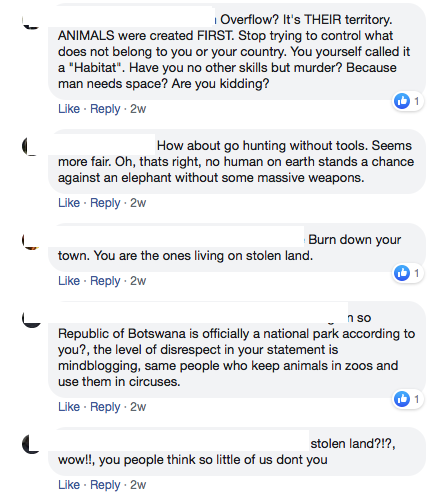

While reports of increased elephant poaching or articles written against elephant hunting circle the globe hundreds of times on social media, reports of people being trampled to death by elephants are barely even noticed beyond the boundaries of Botswana. To add insult to injury, common “solutions” to the problem proposed online involve reducing the number of people in Botswana or throwing them out of their homes, ignoring the fact that this is one of the least populated countries in the world, let alone Africa. #ElephantLivesMatter, #AfricanLivesNotSoMuch

Some of the Facebook comments reacting to Botswana’s hunting decision. The first three comments are by foreigners, the last two by people living in Botswana.

5. The spirit of colonialism is alive and well

African countries are independent, sovereign nations. Botswana, in particular, has a long-standing reputation for stability, democracy and good governance. Yet you would not think so, given the way the rest of the world treats it. The decision taken by the president comes after months of consultations with rural villagers, the tourism industry, conservationists and other stakeholders. It stands in stark contrast to the initial decision to ban hunting, where the “consultation” meetings involved government representatives simply informing people that President Ian Khama had already decided to ban hunting. Yet people who enjoy the fruits of consultative, democratic leadership in their own countries vilify Masisi and venerate former president Khama.

The boycott message is this: African countries and their presidents must stay under the thumbs of the developed world, just like the old days. When an African leader actually listens and responds to the needs of his people, he is branded as “populist”.This legitimises foreigners holding him and his people hostage to their own ideologies. As a former protectorate, Botswana felt somewhat less of the pain inflicted on its colonised neighbours in the past, but it has not escaped the colonialist attitudes of the present.

Conclusion: if boycotting Botswana is counter-productive, what can elephant lovers do?

The calls for a boycott have already done severe damage, and the first of the messages listed here has already been broadcast loud and clear to all African nations. Nonetheless, I believe that some of the damage can be undone if those who love elephants would try a different approach by doing one or more of the following:

-

Re-book that trip to Botswana you cancelled, or book the one you were thinking about before being put off by the recent media storm. Supporting the photographic industry is probably the single best way to keep hunting operators out of pristine wildlife areas, if that is your goal.

-

Try to gain a fuller picture of the situation in Botswana and other African countries that allow hunting. Each country is different, and they have highly variable conservation records. Read media articles that give different points of view. The extreme sides of this polarised debate tend to exaggerate to make their points, so listening to only one side will undoubtedly give a skewed picture of reality.

-

Remain respectful when debating with others on social media, especially when your opponent comes from the country in question. Try to put yourself in the other person’s shoes – how would you feel if your child or spouse was killed by a wild animal in your backyard?

- Support efforts to reduce human-wildlife conflict in Botswana and elsewhere. There are good people doing excellent work on the ground that help rural communities deal with elephants. There is no final solution to conflict, but every bit helps. DM

Gail C. Potgieter (MSc) is a conservationist specialising in addressing human-wildlife conflict with rural communities in southern Africa. She has worked in Botswana and Namibia for 10 years in wildlife management areas and communal conservancies. As an independent consultant, she has a contract with the Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) to help translate scientific articles and reports for the general public. This article was not funded by the NCE or any other party, and the opinions expressed here are the author’s alone.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider