MAVERICK LIFE – BOOKS

Michelle le Roux on her new book, Lawfare, PLUS an excerpt from the book

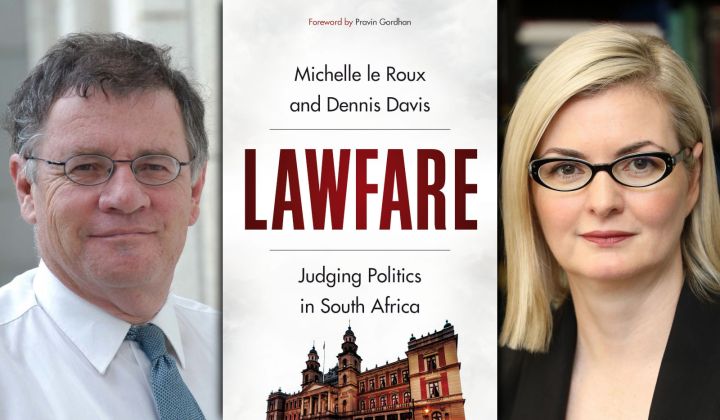

In their new book, Lawfare: Judging Politics in South Africa, Michelle le Roux and Dennis Davis examine what happens when South Africa’s tumultuous political life becomes entangled in courts of law. Throughout the past 50 years, our legal system has been used by both the apartheid state and its opponents. But, the authors argue, in the post-apartheid era, and in particular under the presidency of Jacob Zuma, we have witnessed a dramatic increase in ‘lawfare’: the migration of politics to the courts.

In this Maverick Life exclusive, Le Roux argues that courts alone are not going to align the governance of the country with the ambitions of our Constitution.

Read her op-ed here, followed by an excerpt from her book.

In Lawfare: Judging Politics in South Africa, Dennis Davis and I argue that in our constitutional democracy, courts matter as a site of political struggle, but litigation is an insufficient substitute for functional, engaged politics. Indeed, our constitutional drafters understood this well; hence the importance placed in our Constitution on other key institutions, such as the National Prosecuting Authority, the Public Protector and an efficient policing system to ensure that the core principles of transparency, openness and accountability were adhered to by all organs of state.

Alas, 25 years into constitutionalism – and notwithstanding daily televised court challenges and commissions of inquiry which provide a deluge of revelations and allegations – little, if any, adverse consequences flow for those implicated in State Capture and corruption.

Those consequences obviously should include criminal law enforcement against the kingpins and perpetrators of state capture, corruption and self-enrichment, and civil claims to recover stolen monies, remove disgraced public servants and restore our institutions.

Whatever might be disclosed by way of commissions of inquiry or more indirectly through applications brought to court there is, in addition to a vigorous NPA and Public Protector, a pressing need for the restoration (some would say the establishment) of rigorous parliamentary oversight to actively realise the Constitution’s vision of principled governance.

By contrast, these key institutions have not fulfilled their mandates and, without key changes, courts alone are not going to align the governance of the country with the ambitions of the Constitution.

Indeed, the paralysis and seeming unwillingness of many of our political institutions to perform their constitutional functions have left the courts isolated and perceived as the one functional option to progress a political claim. But, as seen in the cases analysed in Lawfare, it is not an option without risks and it is not a long-term option that can deliver democracy. Once the courts are seen as the only institution doing the heavy lifting required to keep the country on a constitutional path, the risk increases that courts become the targets of politicians. What then happens, if our long history is any guide, weak, executive-minded judges are favoured for appointment and laws changed to extinguish any hope that even litigation could achieve the promises made in the Constitution.

Apart from the revitalisation of key institutions, an active and deliberative politics has to deliver. Sadly instead, and arguably in significant part because of a pernicious response to the failure of our state to focus relentlessly on delivering services and “a better life for all”, deliberation has given way to the rise of populist and identity politics. Instead of movement towards the constitutional ideal of a new South African identity in which the country would belong to all who live in it and the character of citizens rather than their race or gender would hold the key to the future, grinding poverty and disgraceful levels of inequality largely determined by race continue to haunt our country. The previously disadvantaged remain presently disadvantaged.

Bluntly put, if the haves continue to look persistently different to the have-nots, and flaunt their wealth in our unequal society, it is not surprising that politicians spewing racist, divisive slogans gain traction amongst South Africans left without hope or a path to decent work, quality education and training, exemplary healthcare and effective crime prevention.

Ultimately the constitutional project of building a new South African identity must depend on the development of a society that transforms the living conditions and life opportunities for millions for whom, save for the admittedly important right to vote, far too little has changed over the past quarter of a century.

The consequences of similar failures to include those disadvantaged have been seen in a number of countries over the past decade. From Trump’s America, to May’s (or should we say Rees-Mogg and Farage’s) United Kingdom, to Orban’s Hungary or Erdogan’s Turkey, constitutional democracy is under significant pressure. Hence the rise of authoritarian constitutionalism also is not to be discounted – distorting the language of human rights to concentrate and centralise power in the state. And if the recently released Mufamadi report into state security institutions is any guide, we truly need to be on our guard.

All of which means that every single one of us needs to “do our job”. Whether as citizens, voters, the privileged, the empowered, we can each do more to build the society and economy prefigured in the Constitution.

An excerpt from Lawfare: Judging Politics in South Africa by Michelle le Roux and Dennis Davis:

“State capture” (noun)

The Nkandla case illustrates the failure of Parliament to hold the executive accountable, permitting a whitewash and allowing it to dodge its constitutional obligations. It also demonstrates the corollary: the governing party permitted baseless attacks on Madonsela and undermined the constitutional scheme with vexatious parallel processes, instead of respecting a key institution of accountability.

More fundamentally, the case also shows how adjudication is inherently political in nature, responsive to its contemporaneous context. The court’s uncompromising endorsement of the binding nature of the Public Protector’s powers, and recognition of the broad remedial remit of that office, was applauded and welcomed – when Madonsela was its occupant. However, once Mkhwebane took over, and found that the South African Reserve Bank’s mandate should be changed and that the Constitution should be amended to permit this, she, perhaps understandably, relied on the Nkandla judgment for justification for her far-reaching remedial action. The latitude and authority defined by the Nkandla decision were then abused by the current Public Protector, and some of her reports have since been challenged in court.

This reflects the danger inherent in far-reaching court decisions on political questions in a system of precedent: what is desirable in one set of circumstances involving certain individuals can be wholly disastrous when circumstances change or other people are appointed. The question is, how to prevent this? Amending our electoral system to ensure that members of Parliament are directly elected by, and therefore accountable to, constituents may assist. And so would reform of the unilateral powers of appointment of heads of key institutions by the president. We will return to these ideas after examining another case that raises related problems.

Finally, there is another feature of the Nkandla saga that merits rueful reflection. The Public Protector’s report found that

Measures that should never have been implemented, as they are neither provided for in the regulatory instruments, particularly the Cabinet Policy of 2003, the Minimum Physical Security Standards and the SAPS Security Evaluation Reports, nor reasonable, as the most cost-effective to meet incidental security needs, include the construction inside the President’s residence of a Visitors’ Centre, an expensive cattle kraal with a culvert and chicken run, a swimming pool, an amphitheatre, marquee area, some of the extensive paving and the relocation of neighbours who used to form part of the original homestead, at an enormous cost to the state. The relocation was unlawful, as it did not comply with Section 237 of the Constitution. The implementation of these installations involved unlawful action and constitutes improper conduct and maladministration.

Measures that are not expressly provided for, but could have been discretionally implemented in a manner that benefits the broader community, include helipads and a private clinic, whose role could have been fulfilled by a mobile clinic and/or beefed up capacity at the local medical facilities. The measures also include the construction, within the state occupied land, of permanent, expensive but one-roomed SAPS staff quarters, which could have been located at a centralised police station. The failure to explore more economic and community-inclusive options to accommodate the discretional security-related needs, constitutes improper conduct and maladministration.

In the report, the Public Protector set out steps to be taken by the president, “with the assistance of the National Treasury and the SAPS”, to determine the reasonable cost of the measures implemented at his private residence that did not relate to the president’s security. The key point for the reader is that the Public Protector considered other features of the construction work done at Nkandla, such as the marquee area, paving, private clinic, police quarters and helipads, to have also been the result of maladministration and irregular expenditure.

The Constitutional Court’s order, in contrast, only provided that

The National Treasury must determine the reasonable costs of those measures implemented by the Department of Public Works … that do not relate to security, namely the visitors’ centre, the amphitheatre, the cattle kraal, the chicken run and the swimming pool only (emphasis added).

As a result, the list of costly features for which Zuma could have been personally liable in the Public Protector’s report is more extensive than those in the court’s order, and he could have been on the hook for more than the R7.8-million ultimately determined for his personal account (paid with the dubious assistance of a loan from previously unknown VBS Bank).

This raises an intriguing hypothetical consequence that could have arisen had the Constitutional Court not limited the president’s liability in this manner. The president is elected from among the Members of Parliament. Section 47 of the Constitution prohibits unrehabilitated insolvents from being Members of Parliament. Given that the presidential annual salary is R2.9-million, a liability of R7.8-million – or even more if the additional features for which he could have been liable had been included in his tab by the Constitutional Court – could have provided grounds to declare Zuma insolvent, potentially removing his eligibility to continue to serve as president.

The final case considered in this chapter concerns efforts to ensure that Parliament would conduct impeachment proceedings against the president given judicial findings that he had failed to uphold his oath of office, and undermined the rule of law and the Constitution. ML

Lawfare is available at all good book stores.

Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider