See Part 1 here

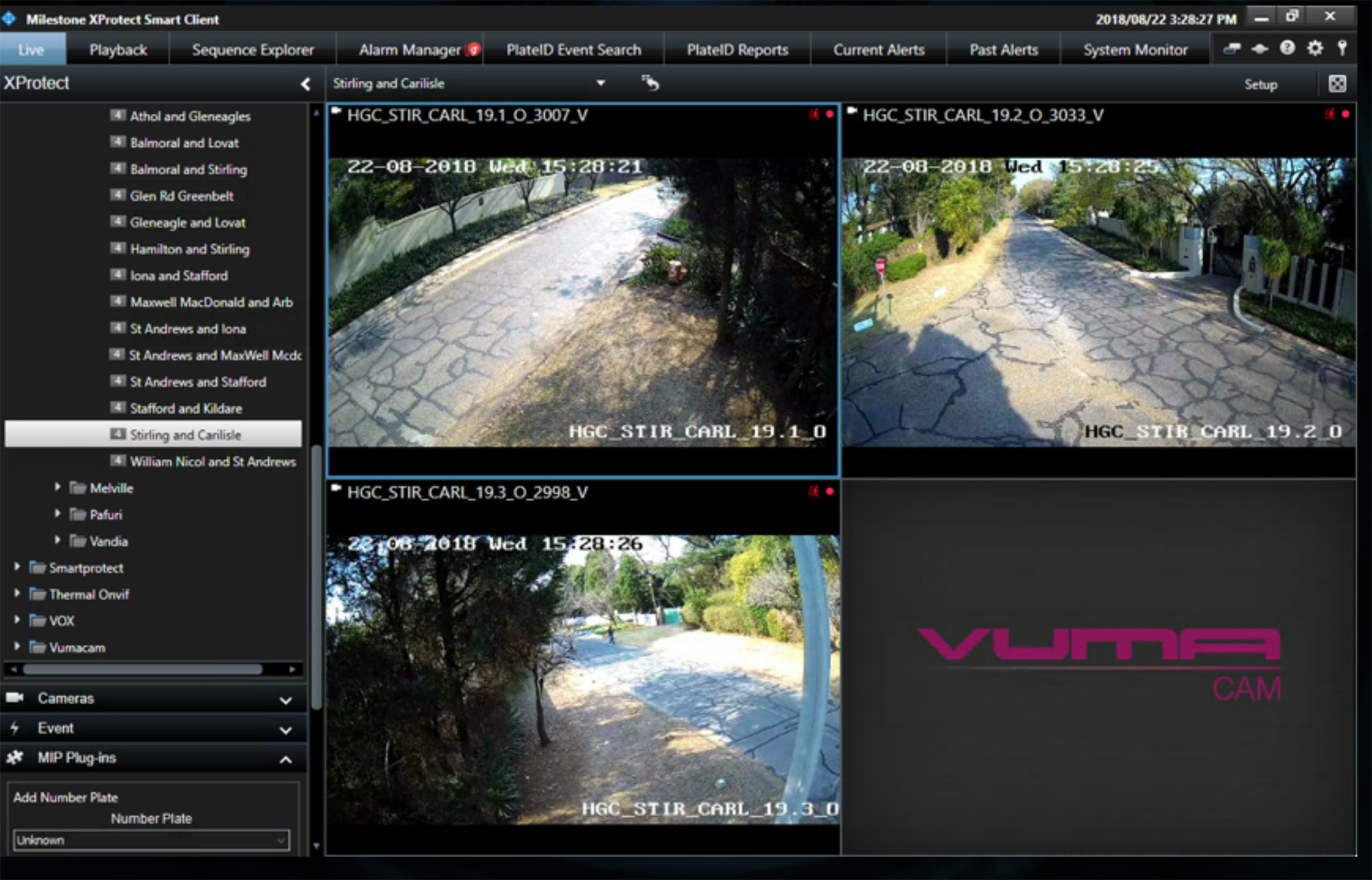

Hanghzhou Hikvision Digital Technologies is a multi-billion rand enterprise that has come to dominate the global video surveillance market over the past five years. It continues making inroads into the African continent too, and South Africa in particular: video surveillance service provider Vumacam are looking to roll out 15 000 cameras throughout Johannesburg in 2019.

But abroad, the Chinese company has met with staunch opposition. In August 2018, the United States passed the John S McCain National Defense Authorisation Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2019. The NDAA regulates US government spending on national defence activities and is voted on annually by the US Congress. The 2019 Act includes a blanket phrase prohibiting US government agencies from using telecommunications and video surveillance equipment manufactured by companies “owned or controlled by, or otherwise connected to” the Chinese government.

The legislation also explicitly names Hikvision, stating that video surveillance and telecommunications equipment from the company may no longer be utilised or purchased for “the purpose of public safety, security of government facilities, physical security surveillance of critical infrastructure, and other national security purposes”.

Along with Hikvision, the 2019 Act prohibits the purchase and use of telecoms and surveillance technology from several other Chinese manufacturers. These include Hytera Communications Corporation, Dahua Technology Company, Huawei Technologies Company, and the ZTE Corporation. Products from subsidiaries or affiliates of these entities are also banned.

The ban on Chinese products, even if fuelling the trade war fire, was not an impulsive decision by President Donald Trump based on his aversion to China. The Act was debated throughout 2018, and both the US House of Representatives and the Senate voted on it before the president signed it into law.

But the US’s suspicion of Chinese tech goes back much further.

In 2012, the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence in the US House of Representatives examined the threats posed to America’s national security by Huawei and ZTE.

The committee stated in its final report on the matter that “Huawei and ZTE provide a wealth of opportunities for Chinese intelligence agencies to insert malicious hardware or software implants into critical telecommunications components and systems” in the US. The concern was that China could steal proprietary information and both military and commercial trade secrets from the US. The committee also warned that China could interfere with any critical US infrastructure dependent on computerised control systems, such as electrical power grids, banking systems, financial networks, or rail and shipping channels.

Central to the committee’s worries was the degree of control that the Chinese government had over the companies’ operations. Neither Huawei nor ZTE could allay fears that the People’s Republic did not wield direct influence over their management. For instance, both companies admitted that China’s ruling Communist Party had a Party Committee placed within the company. Neither company could satisfactorily explain to the US authorities what role the Party Committees played. Huawei is owned by its employees, but has received government grants regularly. A company owned by the Chinese government is the controlling shareholder in ZTE.

At the time of the hearing, trust between the two superpowers was particularly low. In a 2011 report to the US Congress titled Foreign Spies Stealing US Economic Secrets in Cyberspace, the Office of the National Counterintelligence Executive found that “Chinese actors are the world’s most active and persistent perpetrators of economic espionage”.

Although there was never explicit evidence of the Chinese government hacking US systems, the Select Committee on Intelligence found that “the volume, scale, and sophistication” of cyber attacks from China “often indicate state involvement”.

Ultimately the US banned its government agencies from utilizing Huawei or ZTE equipment or components. In March 2019, Huawei took the United States to court over the ban. Chairman Guo Ping said the “US Congress has repeatedly failed to produce any evidence to support its restrictions on Huawei products. We are compelled to take this legal action as a proper and last resort”.

The Hikvision ban comes at a time when Chinese cyber attacks on the US have escalated. In 2015, Chinese president Xi Jinping and then US president Barack Obama agreed that both governments would refrain from commercially motivated cyber espionage. There was a marked decrease in cyber warfare, but Chinese cyber attacks are now on the rise, seemingly in proportion to trade war tensions.

In a report to the US Senate Committee on the Judiciary in December 2018, the US Justice Department stated that, from 2011 to 2018, China was involved in over 90% of all cases of alleged economic espionage that were either conducted by a state or benefitted a state. Over two-thirds of the department’s cases related to trade secret theft were connected to China. The department has declared the Chinese threat a priority. This type of espionage has led to the loss of thousands of US jobs and billions of dollars.

In reality, however, it is extremely difficult to detect and prove state-sponsored hacking, and China and the US have a long-standing history of accusing each other of cyber espionage.

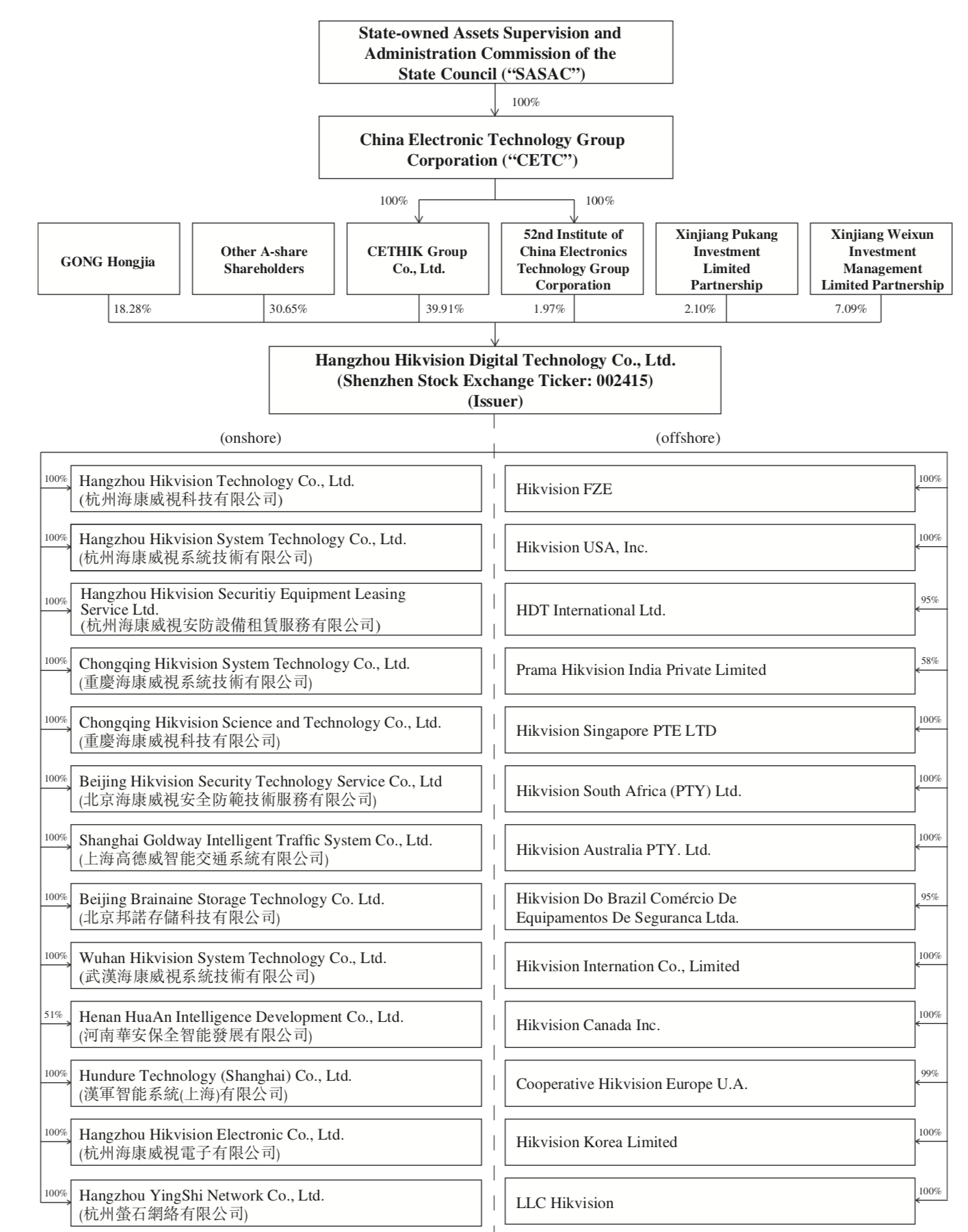

Apart from a general atmosphere of mistrust, Hikvision’s ownership structure immediately disqualifies it as a trusted provider.

Hikvision openly declares in its latest annual report that the Chinese government is a controlling shareholder. Specifically, China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (“CETC”), a 100% state-owned entity, has 100% ownership of two other companies, namely CETHIK Group, and the 52nd Research Institute at China Electronics Technology Group Corporation. Together, these two subsidiaries of CETC own a controlling share of just under 42% in Hikvision. However, the Hikvision annual report states that the company is “independent” from its shareholders in terms of “business, management, assets, organization, and finance”.

But a leaked confidential investors prospectus (from 2016 ) tells a different story. It warns would-be investors: “Our controlling shareholders will continue to be in a position to exert significant influence over our business.” It adds that, despite Hikvision putting in place stringent regulations and systems to prevent interference from the controlling shareholder, “these rules will not eliminate the possibilities that the controlling shareholders or their beneficiaries may improperly control the significant business, finance and personnel” of Hikvision “by way of exercising the voting rights”.

According to the document, the activities of CETC are subject to the supervision of the Chinese government’s State-run Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (“SASAC”). The prospectus warns that CETC is “ultimately under the control of SASAC and the Group (Hikvision Digital and its subsidiaries) is subject to the control of the People’s Republic of China government”.

The American government is not alone in its aversion to companies owned by the Chinese government.

In September 2016, The Times of London reported that retired MI6 officers and security ministers warned that increased oversight of Chinese business in the UK was needed. This was after an investigation showed that UK authorities neglected to carry out a national security assessment of Hikvision’s British operations. At the time, it had emerged that Hikvision had sold over a million CCTV cameras and recorders to the Brits, making it the country’s largest surveillance equipment provider. The cameras were deployed in government facilities, airports, sports stadiums and the London Underground.

In April this year, UK Member of Parliament Karen Lee told The Intercept that she was advocating for the British government to boycott Hikvision – particularly in government facilities.

In October 2018, Australia’s Department of Defence undertook to remove Hikvision cameras from all military facilities.

Mistrust in Hikvision has also found its way into the private sector.

In March 2017, the global security magazine, Defektor International, reported that Genetec, a major global video management software producer, had placed restrictions on its sale of Hikvision products. Genetec obliged new clients using Hikvision equipment to pay a special licence fee. Existing customers had to sign a waiver indemnifying Genetec should a Hikvision device bought from them be used to hack into the customer’s networks.

Genetec feared that Hikvision had purposely placed a secret backdoor in some of their products. A backdoor in software code provides a way for a hacker to secretly access a computer device, and from that point access other devices on the network it’s linked to. A manufacturer can purposely program it into the software, or it can be an honest mistake by the programmer. But its strength lies in that it usually allows someone to access the compromised system from the outside with very little chance of being detected. The attacker can then access data in that network, or take control of devices linked to it.

The idea that a government would oblige a company to build a backdoor into its products is not new. Famously, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation tried to strong-arm Apple into building a backdoor that would allow it access to the iPhone. Apple vehemently opposed it, and the FBI eventually withdrew the case.

There was no evidence that Hikvision products had a backdoor, but Genetec became concerned. Asked if he thought that Hikvision had purposely built backdoors into their cameras, Genetec CEO Pierre Racz told The Defektor:

“Hikvision has publicly made it known that they have a password recovery mechanism for their hardware. And by default, the cameras phone home. But, in some versions of the software, an end-user can opt out.”

What Racz was worried about, was a feature of Hikvision devices that allowed them to automatically link to Hik-Connect – Hikvision’s cloud service. This service allows a customer to store video footage on Hikvision’s servers and view footage via a mobile phone.

This feature was not unique to Hikvision products. The difference, however, was that other companies’ equipment did not automatically connect to their cloud servers; a customer would have to change the factory setting of the product to establish a connection. In Hikvision’s case, the default factory setting was for the camera to connect. So, unless the customer explicitly checked for this, they would be unaware of the connection.

The motivation behind such a default connection is to make the initial setup of the camera easier. But there was also a suspicion that Hikvision would secretly access customer footage or camera networks via the connection.

In reaction to Genetec’s move, Hikvision’s international marketing director, Keen Yao, told the Defektor that Genetec’s actions were “politically motivated”, saying they were aimed at negatively influencing “perceptions about Hikvision’s approach to cybersecurity”. Yao rubbished claims made by the 2016 Times of London article.

Addressing concerns about interference in the company by the Chinese government, he said that Hikvision was a “commercial entity” and that the company’s management was in charge of operations. He stated that Hikvision had “never intentionally put a backdoor into firmware or software” and that it never would.

In the year following Genetec’s actions, Hikvision changed the default factory settings on its equipment so that devices would not automatically connect to the company’s cloud servers. Customers now had to actively choose whether or not they wanted to make the connection.

But in May 2017, there was another blow to Hikvision’s credibility. The US Department of Homeland Security issued an advisory notice warning about security problems in several Hikvision camera models. The Department routinely releases such warnings about cybersecurity threats. Companies from all countries, including the US, are subject to scrutiny.

The advisory stated that affected cameras were ‘remotely exploitable’ and that this required a ‘low skill-level’. An anonymous hacker of average capability could hack the cameras and take control of it. The Department credited the discovery of the security threat to one Montecrypto, an anonymous researcher.

Hikvision worked with the DHS to resolve the problem. Both entities referred to the issue as a “privilege-escalating vulnerability”.

But Montecrypto had labelled it a “backdoor”. According to the researcher, the jury was still out on whether or not it was purposely planted, stating: “It is nearly impossible for a piece of code that obvious to not be noticed by development or QA teams, yet it has been present for 3+ years.” The researcher said that the “vulnerability started to quietly disappear from new firmware” that became available from the start of 2017 – after Yao had stated that the company would never intentionally install a backdoor in its products.

Hikvision’s explanation was that the ‘backdoor’ resulted from a piece of test code accidentally left in the firmware by a developer, according to Montecrypto. The researcher said that this was a plausible explanation since Hikvision would probably at least tried have to hide the ‘backdoor’ if they had placed it there on purpose. To boot, the ‘backdoor’ was present in models used in China as well, making it less likely that Hikvision had purposely created it.

Backdoor or not, the incident caught the eye of the United States Congress in January 2018 and it did little to allay America’s fears about Hikvision. Barely seven months later, its products were banned in US government facilities.

Apart from the potential theft of proprietary information, state-sponsored cyber espionage by China poses another threat to South Africans.

While the United States and China clearly sit at opposite ends of the table when it comes to matters of national security, the People’s Republic’s official relationship with South Africa is one of co-operation. As part of BRICS, both countries attended the 8th BRICS National Security Advisers (NSAs) meeting in eThekwini last year. The meeting centred on the BRICS countries’ “collective commitment to co-operate in preventing, mitigating and combating security threats,” according to a statement released by South Africa’s State Security Agency.

Discussions included terrorism, peacekeeping, transnational organised crime, and security in the use of information and communications technology (ICT). Surveillance cameras and related equipment that link to the internet are a fast-growing part of ICT. More specifically, BRICS countries are developing an “intergovernmental agreement on co-operation” with regard to ICT security.

At the meeting, a proposal for a BRICS Intelligence Forum was also discussed, but no final decisions regarding a more formal structure materialised.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/heida-surveillance-part2-PIC-5-DHS-WARNING.jpg)

While cooperation on security matters has only been part of the BRICS discourse since 2011, countries collaborating on matters of intelligence is not new. The Five Eyes is an intelligence alliance of English-speaking countries, born out UK-US intelligence collaboration of the Second World War in 1946. As the Cold War grew, so did their membership, with Canada, Australia and New Zealand joining before the 1950s drew to a close.

More specifically, the countries have a formal agreement to co-operate with regards to signals intelligence, aka SIGINT. SIGINT is a blanket term for collecting information communicated through electronic signals, including communications. This includes Internet traffic, or phone calls, for instance.

The BRICS countries lag behind the Five Eyes, with the group as yet unable to give effect to its security agenda, despite the apparent political will to do so. This is according to research by Brazil’s Igarapé Institute, an international think-tank focused on solutions to global security issues.

But it is conceivable that should the Hikvision have access to the cameras within the Vumacam system, that the Chinese government may share this feed with the SSA. The trade of data – such as video surveillance footage – between SA’s State Security Agency and China is not out of the question, says Gareth Newham of South Africa’s Institute for Security Studies.

Newham explains that, at least at a political level, the Zuma administration had a healthy relationship with China.

“We know that David Mahlobo, when he was the national minister of State Security, visited China a number of times. The Zondo Commission of Inquiry into State Capture also heard testimony that former Police Minister Nathi Nhleko recruited 16 people who underwent intensive security training in China.

“One can assume from these examples that there might be secret security-related arrangements that could include the sharing of information. We can’t say for sure, but one can assume there was some kind of relationship that wasn’t purely political.”

Earlier in 2018, President Cyril Ramaphosa’s High Level Review Panel on the SSA released a damning report about corruption within the agency. As yet, no arrests have been made.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/heida-surveillance-part2-PIC-7.jpg)

But there’s another reason why China may want footage of South Africans. Last year, the Zimbabwean government signed a deal with Chinese company CloudWalk Technology, according to Foreign Policy. The trade-off: CloudWalk would be allowed to use footage of Zimbabwean citizens to develop its facial recognition technology, which up to now has been largely developed based on white male faces, and therefore proved dangerously inaccurate. Without new data, it is impossible to further develop such technology for the global market.

We sent the State Security Agency several questions regarding the espionage threat posed by China. We also enquired about the relationship between the State Security Agency and the Chinese government, and the potential trading of intelligence. Agency spokesperson Lebohang Mafokosi stated:

“The SSA remains alert to threats to national security, including cybersecurity in all its manifestations. In this regards, all necessary measures are and will be implemented whenever necessary. This is done in consultation with all the relevant partners within the security cluster and other stakeholders.”

Daily Maverick also sent detailed questions to both Vumacam and Hikvision about the potential for government espionage in South Africa via the Vumacam system.

Hikvision responded:

“First, we’d like to reinforce that there is no evidence anywhere in the world, including South African and the US, to indicate that Hikvision’s products are used for unauthorised collection of information. Hikvision has never conducted, nor will it conduct, any espionage-related activities for any government in the world. Second, Hikvision strictly follows the laws and regulations in all countries and jurisdictions where it conducts business, including South Africa. Hikvision is committed to the integrity of its products and industry-leading cybersecurity standards.”

Vumacam representative Ashleigh Parry did not specifically address questions with regards to potential government espionage through their network, but stated that Hikvision cameras had safeguards to protect them from hacking and that the product continued to meet Vumacam’s robust testing processes.

She said there was “a need to balance public interest and privacy with our imperative in delivering public safety. We have met and exceeded the highest standards in this regard. We will further abide by any future policy changes, rulings or other regulatory constraints made by our government or other authorised relevant regulatory bodies. We are willing to engage with all stakeholders in this process.” DM

Heidi Swart is an investigative journalist who reports on surveillance and data privacy issues.

This story was commissioned by the Media Policy and Democracy Project, an initiative of the University of Johannesburg’s department of journalism, film and TV and Unisa’s department of communication science.

Illustration: Leila Dougan

(Image sources: Ibrahim Rifath / Unsplash / Johannesburg Skyline / Wikimedia / Pawel Czerwinski / Unsplash)

Illustration: Leila Dougan

(Image sources: Ibrahim Rifath / Unsplash / Johannesburg Skyline / Wikimedia / Pawel Czerwinski / Unsplash)