BOOK EXTRACT

Cul-de-sac: ‘It’s not a meal, it’s a happening!’

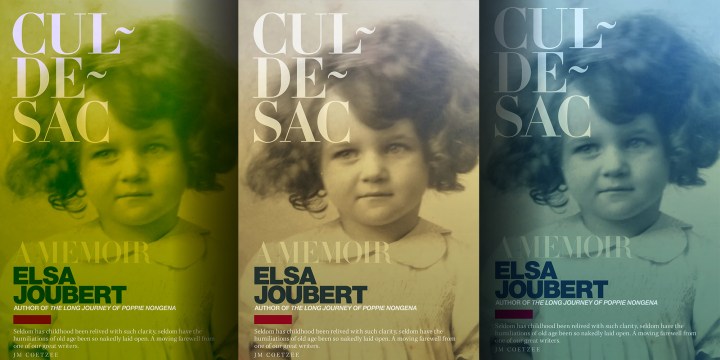

Elsa Joubert is one of South Africa’s most celebrated writers. ‘Cul-de-Sac’ is a memoir about life after the death of her husband. Moving into an upmarket retirement home, she has to come to term with the loss of independence, friends who die and the process of ageing. Nobel Laureate JM Coetzee wrote of ‘Cul-de-sac’ that ‘Seldom has childhood been relived with such clarity, seldom have the humiliations of old age been so nakedly laid open. A moving farewell from one of our great writers.’

Rita and I decided we wanted to invite two old friends, Kitty Petousis, actress, and Alice Goldin, painter, to lunch at Berghof.

It can be quite festive in the dining room. First decide on a date. We are busy people. An important consideration is when our cleaners come. Monday is out for me, Tuesday is out for Rita. On Friday my study is cleaned. Wednesday is difficult, because the hairdresser comes to Berghof, and who knows, by that time our hair may be a mess and we may want our hair done.

Thursday seems best. We want to give our guests a choice: Thursday the 4th or Thursday the 11th of November. I’ll make the arrangements, because Rita’s eyesight has deteriorated and it’s hard for her to dial new numbers. Kitty and Rita are 91 years old and Alice and I 92. Kitty still drives, has a new car and will pick up Alice.

Now we have to think it through, hatch our plans with care. Alice walks with difficulty, hardly walks at all, in fact, and can’t make the trip down the long corridor to my or Rita’s apartment for a glass of sherry and then back again to the dining room. I want to do things properly and don’t want to forfeit the sherry. Solution: Before lunch I’ll place a bottle of sherry on a small table in the attractive sitting area of our dining room, Berghof will supply the sherry glasses. We’ll meet our guests at Reception at noon and take them straight to the dining room by lift. Rita says she will be too tense and will go ahead to the dining room on her own and wait with the sherry.

I’m standing at Reception. My guests aren’t turning up. The wind is howling outside. Early southeaster. Black southeaster.

I’m getting tense. I go outside to the gate, then inside to Reception. My newly cut hair is standing up. As in my childhood.

It’s quarter past 12 when Kitty’s little white car swings in at the gate. She must stop and press a button for Reception to let her in. She’s too far from the button, gropes anxiously in the air, I’m almost on top of her bonnet with trying to signal how to do it, the wind is too strong, it pushes me back, somebody coming in presses the button for her and the gate slides open slowly. “Go now,” I say, but she can’t hear me, the wind scatters my words. “Go now before it slides back, if it slides back it will squash you, go, step on it, now, please.” Kitty’s car enters slowly and I hurry to help Alice from the car before she parks. I have StomJapie with me to help me against the wind.

She struggles with the door, the wind blows her back, her safety belt is still fastened, Kitty tries to unfasten it, I pull from this side, I grab her hands and place them around StomJapie, but she pushes at an angle, we totter up against the garage doors, now she and I are both clinging to StomJapie, battling back against the wind that’s threatening to blow us away, then we’re around the corner and sheltered. But Kitty turns back into the wind and to the car. She has to fetch the flowers. We wait for her, she holds her hair with one hand, the other clutches a pot plant, the three flowers on their leafless stems have been blown about by the wind and are drooping this way and that. We leave the plant at Reception and struggle around the corner with StomJapie to the lift. We descend, the door opens and Rita is there. “I’m waiting for you, I was coming to look for you.”

At last we’re sitting down, and I pour the sherry. We all need a dash of alcohol. “I love a little drink before a meal,” says Alice. I’m pleased, I knew it was her kind of thing. The dining room is filling up, after the drink we move to the table. The soup is well received, broccoli soup. Berghof is known for its soup. But somebody has noticed us four nonagenarians at the small square table, one of the residents, George Hendrie, comes walking across to our table, very pleased. He bends over Kitty, he worked at her family hotel, the Vineyard, for years.

Kitty in her impulsive way is overjoyed to see him, she half gets to her feet to talk to him. Then George’s wife joins us.

Now things are really humming.

And old acquaintances come to greet Alice, we can hardly eat. Alice is struggling with her salad, I watch her anxiously.

With one hand, her eyesight is bad, the peas scatter away from the fork, the tiny tomatoes refuse to be pinned down, but she perseveres until her plate is empty. Green bean casserole. The meat is tender, we have no trouble chewing. It’s not our best meal, but it’s passable. Another acquaintance comes over to greet Alice. Alice looks so fragile, but her grey head is clear.

All four of our heads are clear. Southeaster or not. The dessert was a problem. There’s a choice of two, but we have to say in advance in the morning which one we want. I couldn’t phone my guests about something so banal, so I ordered two of each, both very good: crème caramel or ice cream with chocolate sauce. I tell Rita our guests have first choice, then we take what’s left. We’ve hardly started eating when an old friend of Alice, Rita and myself comes up to the table: Hannah-Reeve Sanders, former superintendent of Groote Schuur Hospital, a new arrival at Berghof. She’s overjoyed to see Alice, presses Alice’s slender body to her, adjusts her dress, which has half descended over the bare shoulder – how chaste and tender her white skin seems. Hannah pushes it back and with another squeeze the affection radiates from her to Alice and all of us.

She joins us at our table, she’s eaten already and in her lively manner she tells us about her life. She grew up in Piketberg, her father was an immigrant trader who was given a home there years before by a farmer. He went to fetch his bride from Lithuania to Cape Town; he later added another room to his house, Hannah and her brother were born there, they grew up and went to school with the farmer’s children. We’re still friends, she says excitedly, they’re coming to fetch me to spend Christmas with them in Gordon’s Bay. Isn’t that a wonderful story?

We have coffee together. George and his wife and others come to greet our guests. Do you know what? Kitty says excitedly. It’s not a meal, it’s a happening!

Back to the lift. On the long trip to my apartment, to which I’ve lured them for a Middle Eastern delicacy that my granddaughter, who had visited a boyfriend in Bahrain, brought back for me, Alice and I are conjoined over StomJapie. Bumping against doors and bashing into dry flower and leaf arrangements on the floor at apartment doors, with Rita and Kitty following, still announcing that it’s a happening, that’s what it is. We sit down and they munch away at the Middle Eastern dates with nuts inside and a kind of decoration on the outside. They admire my study that is untidy in an acceptable sort of way with piles of paper stacked on my desk and pushed back up against the wall. Some of them have slipped down at an angle. Last time Alice said it was a lovely room, but “too tidy”… Now I’ve shown her my true self, as I intended.

Once more down the corridor. The southeaster is still howling and we have to get them to the car. It’s old StomJapie again, but this time I handle it better. Alice in front and my arms around her from the back as you would lift someone onto your bicycle, and onto the handlebars. Together we push and heave against the black southeaster that descends upon us as if on prey. A car door that Kitty opens swings back and winds us both; once Alice is inside we have to push to get the door to close.

“Go, Kitty, go.” The car is on the line that controls the gate, the gate starts moving jerkily and closing in on the car. Kitty is bent over Alice, sees nothing. “Leave Alice’s belt, Kitty, step on the accelerator.” But it’s too late, the gate sneaks past them, unstoppable once it’s set in motion. “Reverse a bit, Kitty!” I shout. “Back onto the line, but then go, leave the belt, just go!”

But she doesn’t hear me, doesn’t see me when in the howling wind I let go of StomJapie for a moment, waving my arms in front of the windscreen, and then start spinning StomJapie around – what would my children say if they had to see me now, me, so feebly tremulous with them and having to be helped with everything? I do hear a droning – she steps on the accelerator and the car surges ahead – and I shout: “Keep stepping on it, Kitty, otherwise you’ll be squashed flat like a concertina!”

The unstoppable gate only just lets them squeeze through.

They slowly emerge from the gate, down the street. They’re gone. I grab StomJapie, the wind whooshing in my ears. As close to the wall as we can, we brave the wind, round the corner, stagger to the entrance. Rita has sounded the retreat and taken to her apartment. I walk into the otherworldly silence of Reception. Done for.

“Mrs Steytler,” I hear Reception say, “the plant.” Two of the large pink flower-faces are looking up at me, the stem of the third has been snapped by the wind, it’s hanging at an acute angle to the floor, a small, sharp bitterness in the stalk. Sorry, Flower, it happens, we also snap here in Berghof. Grateful to StomJapie who takes the plant to his bosom. I cast myself down on my bed. Finished. I have ENTERTAINED for the last time.

A few months later we hear that Alice has died. And in the following week, Kitty too, after a stroke.

That’s how it is to be old. Up and down. DM

Cul-de-sac by Elsa Joubert is published by Tafelberg. One of the authors who were collectively known as the Sestigers, her novel, Die Swerfjare van Poppie Nongena, translated into English as The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena, was selected as one of the 100 most important African books of the 20th Century. This poignant extract is from her autobiographical work, Spertyd, translated into English by Michiel Heyns as Cul-de-sac.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider