Over the past 25 years, there have been many plans, programmes and proposals on how to tackle this complex problem, but as we know, progress has been slow, largely as a result of the bureaucratisation of the process. As a consequence, South Africa has failed to restore land rights to the majority of the South African people, as is mandated in the Constitution.

The recent debates on “expropriation without compensation” have again highlighted the emotions and deep divisions in our society related to the inequality of land ownership, and how important it is to address this issue. This reality necessitates urgent action.

In light of the unsatisfactory performance of the land reform programme over the past 25 years, there is now an opportunity for all South Africans and specifically the private sector (corporates as well as small and medium enterprises in the respective urban and rural value chains, property owners, property developers, agribusinesses, commercial farmers and so on) to contribute meaningfully to the land reform imperative.

This comment presents some guidelines and a framework to illustrate how the private sector and individuals can make a contribution to land reform. This potential contribution would originate from the altruistic or benevolent behaviour of private individuals or companies. In recent months, there have been a number of examples of companies or farmers acting altruistically by donating land for (mainly) housing development. The typical voluntary contributions proposed in this framework will therefore be limited, but could be enhanced by the government through various off-budget incentives, as well as smart and efficient systems. A process and system of incentives will be required.

In this respect, we also highlight potential mechanisms to be implemented by the government to secure greater participation by individuals and the private sector (specifically the wealthy elite and large businesses). In the end, it is hoped that this process could accelerate land reform/redistribution and reduce concerns about fiscal budget constraints, legislative change and red tape. This framework is based on a recent working paper by Johann Kirsten and Nick Vink presented at a workshop at the University of the Western Cape.

Voluntary actions by the private sector and state incentives

The approach proposed in this comment relies strongly on the voluntary contribution of all South Africans to the goal of equitable land ownership. To make this work at scale and to accelerate the process, there should be some form of quid pro quo, or alternatively a list of incentives that will encourage participation.

In the absence of such incentives or enablers, one can only rely on the altruistic behaviour of individuals and companies which, per definition, is latent in rational individuals who often only have their own interests in mind. This altruistic behaviour can, however, be harnessed by smart incentives to nudge individuals and private business in contributing to the social good of a stable and equitable South Africa.

There could be many such incentives or enablers but we argue that there are, in essence, six big “tickets” to activate voluntary contributions to the land reform programme. These are:

-

An easy process and one-stop shop to submit the record of the transaction for recognition (we can call this the “land reform rainbow register”);

-

The recognition mechanism could bring about an important benefit to the former owner. This could be in the form of some empowerment recognition level or financial or other inducements. The revised Mining Charter’s provision on “once empowered, always empowered” of existing mining rights might serve as an example of a particularly important commercial incentive for current farmers and owners of land to participate in. At certain thresholds, either cash or quantity, the property and its owners might be deemed fully empowered. This status remains with the property as an enhancement and has significant commercial value. In attaching the status to the property, it becomes generally applicable so would pass constitutional scrutiny and would most probably be value enhancing;

-

The speedy transfer of title deeds/long-term and tradable leases to eligible beneficiaries of land reform, including those who occupy land already procured for land reform purposes;

-

The allocation of new water rights (or water released by existing farmers through efficiency gains) to the existing and new enterprises (owned by the beneficiary). This will again allow the existing farmer to dispose of land and at the same time ensure the successful establishment of smaller farms on irrigated land;

-

The rooting out of corruption in the land reform process. This could include the restructuring of the Land Bank and establishment of a Land Reform Fund where acquisition grants, subsidised loans and subsidies for on-farm improvements can be accessed. Access to the Land Reform Fund can be used to leverage the donation of land by existing owners. This capital (at preferential and subsidised terms) allows farmers to dispose of land for land reform purposes but at the same time provides them with finance to expand their existing business and employ more workers; and

-

Adaptation to the process of subdividing land and improving the process and systems of land administration could also act as useful enablers.

Fundamental to the process is the element of recognition, reduced red tape, ease of subdivision, transfer of rights and a decentralised process of implementation at the local level.

The rest of our comment suggests the potential areas and mechanisms through which South Africans can contribute to the land reform programme. Before we deal with these aspects in detail, it is important to have some perspective on the land reform statistics and how much progress has been made with redistributing farmland (which constitutes by far the largest part of South Africa’s surface area).

The real numbers on land reform in South Africa: 1994-present

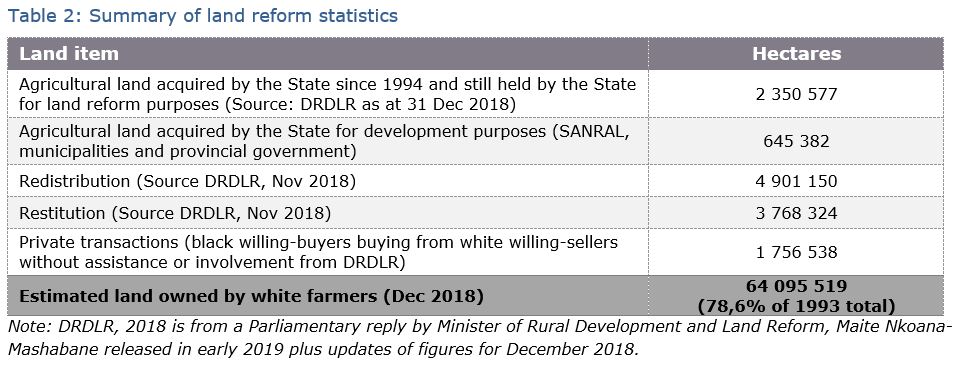

With recent numbers acquired from the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR), we are able to report progress with land reform to date. First, it is important to understand the total surface area of South Africa and the geopolitical distribution of the total surface area as a result of the colonial and apartheid past of our nation. The data presented here are mainly related to farmland and thus provide us with little information on ownership patterns and so on for land in urban areas for residential, industrial or business use.

Total farmland as defined by the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (Daff) covers around 97 million hectares (ha) of which 81.4 million ha of farmland were under freehold tenure in 1993. Since 1994, a total of 3.9 million ha of farmland was lost to urban development, mining and other non-agricultural uses, reducing the area of freehold farmland to 77.5 million ha.

Of the 77.51 million ha, a total of 8.67 million ha (or 11.2%) has been allocated to beneficiaries via the land redistribution and restitution programmes since 1994. We estimate through our own research and analysis of deed transfers, that black farmers acquired at least an additional 1.75 million ha (2.2%) privately without the support of the government programmes. This is an undercount, as the Deeds Registry does not record the population group of individual owners, nor can the ownership of trusts, corporates and so on be identified in the register.

Due to the suspension of the initial redistribution programmes in 2006, very little redistribution to individual owners has happened under the auspices of the state, while the state has acquired, and still owns, a total of 2.35 million ha (or 2.8%) of farmland under the Proactive Land Acquisition strategy (PLAS).

Furthermore, many individuals and communities, especially in the urban areas, elected to receive financial compensation rather than land as part of the restitution process. To date, this accounts for the equivalent of 2.92 million ha. Urban land makes up about a fifth of this (581,045 ha).

The numbers presented in Table 2 remain incomplete and underestimate the extent of land reform. In addition to the problems mentioned in ascribing land to different population groups, it also excludes part ownership (eg under equity-sharing schemes), the 2.34 million ha of farmland for which communities elected to receive financial compensation instead of the transfer of the land, as well as the 780,000ha transferred under tenure reform. So, the total hectares of land rights restored remains a conservative estimate, with the real number probably closer to 25% of all farmland previously owned by white commercial farmers.

A fast-track land reform programme implemented by the private sector

Chasing land reform targets per se is not a useful exercise, since land reform should be a permanent feature of our economic programme of redress. For this reason, we should rather focus on the process and mechanisms of delivering land in an orderly and rights-based way to the majority of South Africans. We need a “fast-track” programme.

The fundamental premise of this fast-track programme (which is only one approach in a suite of options to be implemented by government) is that private landowners either donate land voluntarily (for business, housing, industrial use or farming), give up some of their time and expertise to mentor new entrants to business and farming, or contribute some combination of these, as the case may be.

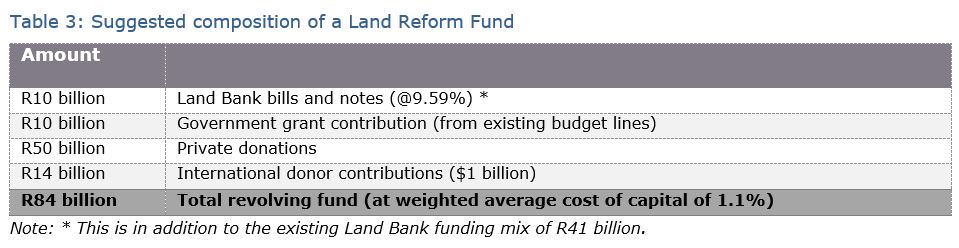

The second dimension of this fast-track land reform programme will include a mechanism through which the private non-farm sector can contribute, namely a Land Reform Fund administered through the Land Bank. Sources of capital could include:

-

Land Reform Bonds issued by the Land Bank with the necessary government guarantees. Investments in these bonds will be by domestic and foreign investors, multilateral and bilateral donors and private social investment entities;

-

Donations by companies, private individuals, and international donors;

-

A state grant contribution in the form of farmer support programmes, using funds currently allocated to the Comprehensive Agricultural Support Programme (CASP), the Recapitalisation Programme (Recap), and so forth; and

-

Joint-venture financing models, particularly implemented by agribusinesses, large commercial farmers, property developers and the commercial banks, among others. The agribusinesses and commercial banks, through the Agricultural Business Chamber and the Banking Association of South Africa, have already committed to matching the state’s budget for land reform in the interest of fast-tracking progress in the form of loans at a preferential rate over a set period.

These sources of funding (most of it provided below long-term mortgage bond rates or not interest-bearing at all) should allow the Land Bank to provide finance to beneficiaries (and commercial farmers donating land) at subsidised interest rates and beneficial terms such as deferred capital repayments or deferred interest payments.

For example, banks in South Africa lend money against urban residential mortgages for a period of no longer than 20 years. In agriculture, neither the Land Bank nor the commercial banks are eager to lend for longer than 10 years. On the other hand, in the past, the Land Bank and the Agricultural Credit Board gave mortgages of up to 40 years (and for up to 65 years in the original irrigation settlements earlier in the 20th century). Couple this with interest rate subsidies and the phasing in of provisions of the National Development Plan (NDP), and many more individuals and/or farming enterprises could afford access to land for farming purposes and could access bridging finance and seasonal finance at affordable rates of interest.

Above all, the proposed Fund provides a unique opportunity for South Africans to build social and financial capital by creating an investment opportunity for individual and corporate capital market participants to make a meaningful contribution to land reform. This scenario decentralises the land reform process by leveraging private sector expertise and capital and stands in support of the government’s intention to create jobs and boost investor confidence in the country.

While the housing and agricultural sectors are at the forefront of land reform, the capital required for such a programme far outstrips the capacity of these sectors. Hence, opportunities will be created for other investors to contribute to the challenge of restoring social justice, equitable land ownership, decent housing and equitable economic opportunities.

White farmers were not the only individuals who benefited from the old regime, and most of the beneficiaries of apartheid live in urban areas. Therefore, this also includes a call for voluntary financial donations from the financial services industry, the mining and manufacturing sectors and other non-agricultural sectors. This is specifically relevant to businesses that do not own any landed property.

The end game of this process is to unlock economic growth and employment opportunities and to create a vision of a dynamic and vibrant rural economy, to restore decent life and economic opportunities in the urban areas created through a better-serviced local community and much more spatially integrated and improved urban areas.

Describing the scope and role for business (and individuals) in land reform

The process we are proposing is one where every South African can buy into land reform, as a conscientious contributor or a responsible recipient. The options that can be followed are diverse and can be tailor-made for each entity’s unique circumstances.

Donate land

This implies the voluntary release of land (by mines, other businesses, churches, municipalities, SOEs, government departments or absentee landlords) directly to beneficiaries. For proper administration, the state will keep a record of these land parcels and could even provide a certificate of recognition to the donor. This certificate may entitle the holder to certain benefits such as procurement preferences or a wide range of preferential financial arrangements, including tax breaks and so on.

The recent donation of land by a large mining company for housing development is an example where land not being used by a mining company can be donated voluntarily to help with housing development, as in this case, or for settling new farmers. Mining companies own large tracts of farmland and donating this land to farmers and/or partnering with agribusinesses and a land reform fund with blended finance could be an ideal mechanism to settle family farmers.

In urban and peri-urban areas, we refer to buildings (underutilised, vandalised, hijacked, or empty) as well as vacant and unoccupied urban land owned by the government, municipalities, private owners, and SOEs. Again the principle of donation of this land and property to an entity (linked to Cogta and Human Settlements) with supportive finance and urban and spatial planning and development can immediately relieve the pressure on land needed for housing and shelter. This also creates an ideal opportunity to deal with the legacy of apartheid spatial planning.

Most municipalities own land (often in urban and peri-urban areas) that is leased to tenants — often white farmers — which presents an immediate source of redistribution by introducing certain requirements/conditions in terms of housing development and peri-urban agriculture for black commercial farmers. The government could instruct municipalities to ensure that tenants provide housing development or farming activities for black farmers on at least 50% of the land they lease from the municipality.

Housing developers and local government need to join forces by rapidly using this opportunity to renovate buildings and invest in bulk infrastructure on the vacant land. In essence, developers and municipalities will “donate” their expertise and skills and co-finance to relieve the housing backlog by being proactive. This will, if implemented with rapid speed and at large scale, ease the land pressure and contestation in urban areas and bring people closer to their workplaces. More importantly, this could improve people’s living standards and reduce transport costs for poor and lower-middle-class families.

As in the case of farmland, finance can also be obtained from the Land Reform Fund, which was formed through the donation of financial assets, in addition to the current Human Settlements budget.

Privately owned farmland next to rural towns is highly contested and should be addressed within the ambits of this plan. Farmers and municipalities should establish models whereby the joint development of these mainly unutilised farms (due to contestation and crime) could be activated to satisfy the increasing need for serviced plots and houses. Donation of the land by farmers, which would be formally recognised under the land reform programme, would go a long way to creating social stability and reduce racial tensions in these communities.

For commercial farmers, this is also an opportunity to implement the redistribution of farmland on their terms and in collaboration with their choice of beneficiaries — being workers or other black entrepreneurs. They can do this in a number of ways:

-

Donating land without any ties attached;

-

Sub-dividing land and allocating viable portions of land to workers (for farming or housing), tenants and potential beneficiaries. Again, ease of subdivision is key and efficient and quick registration of new owners should be in place;

-

Establishment of farmworker housing or villages where workers have title deeds and access to services, education and health facilities. (Many farmers will be happy to subdivide their farms and develop decent housing with full title deeds to their workers if applications for subdivision of land can be fast-tracked and sensibly implemented); and

-

Joint ventures with privately identified beneficiaries (according to the criteria established by the panel). These joint ventures could access subsidised capital, water rights and market contracts. At the same time, agribusiness should provide well-integrated support services for these new entrants.

This idea largely operationalises the opportunity for commercial farming unions to offer land for the land reform programme in a proactive manner. The commercial farming sector could assemble a process whereby well-located farmland is identified and committed for land reform, beneficiaries selected, and finance, mentorship and support put in place. This, in fact, sees the private sector, in collaboration with beneficiaries, make a substantive contribution to the land redistribution process on its own terms, but keeping in mind the outcome of equitable land ownership.

In-kind donations and support to establish new farmers

Agribusinesses (in some cases in co-operation with provincial governments) could also play a role by “donating” time and skills for mentoring, training and assisting new farmers on farmland released through this process. The success of the new farmers would be in the best interest of agribusiness because they will be potential clients, especially in terms of the NDP’s promotion of farming development that prioritises labour-intensive crops that are also seeing a growing demand in the global market.

Establishing a farming business from scratch is very difficult given the large land and capital costs. It is unlikely to be achieved successfully without the assistance of the state — it was not possible in 1920 and will not be in 2020.

However, there are a number of areas where the private sector can deliver these services on behalf of or in collaboration with the state. There should, therefore, be a firm commitment from agribusiness firms and financiers to provide some of the elements of this support package on behalf of the government — mainly related to information, expertise, extension services, market access, and preferential finance.

However, there remains an important role for the state in order to create a decent chance of success for newly settled farmers. The main elements of a successful farmer support programme could include:

-

Mechanisms to subsidise capital needs. This includes full or partial direct subsidies, delayed payments and phasing provisions as explained earlier;

-

The annual payment for land acquisition is spread over a longer period — perhaps 40 years (and not the standard 10 years prevalent in agriculture). It is also possible to include elements such as deferred payments whereby beneficiaries are given a five- to a seven-year grace period before repayment of capital and interest (at subsidised rates) kicks in; and

-

Subsidies for on-farm improvements and infrastructure (fences, conservation works, reservoirs, boreholes, pumps, cattle pens) could be provided via the Comprehensive Agricultural Support Programme (CASP), or the newly envisaged producer support policy of DAFF, but the payment process should be changed. It should work on a co-funding model and state reimbursement according to government-approved tariffs. Farmers will pay for the improvement (using their own resources or a loan from the Land Reform Fund) and then claim the refund from the relevant government office based on proof of expenditure and on-site inspection to verify actual expense. The refund can be offset against the outstanding credit amount.

Some form of social support initiatives such as medical services and education as well as a small start-up salary grant could also be considered to facilitate a smooth settlement process.

Donate to the Land Reform Fund

The personal wealth of the elite, including business leaders and urban professionals, vests in various financial assets and is substantial. This could be a valuable source from which voluntary contributions can be requested to fund the implementation of land reform in all its many dimensions.

Donations to the Land Reform Fund by individuals or asset managers should also be incentivised through tax relief and other benefits. We expect, however, that the main vehicle for such investments will be the envisaged land reform bonds. There is already considerable international interest in investing in such bonds with the understanding that National Treasury will issue the necessary guarantees.

The creation of the Land Reform Fund should be a simple process whereby government funds, capital raised through the land reform bonds, and donor funds could be merged into a fund which should be easily accessible by implementing agents and beneficiaries of land reform.

It will be the main element of a blended financing model for land reform, whereby state funds, donor funds and the private sector will facilitate the funding of land reform in a much quicker and cheaper way without placing an additional burden on the fiscus.

As shown in Table 3, it is possible to blend all these funds and thereby reduce the cost of capital to a mere 1.1% which should allow the fund to on-lend to beneficiaries and benefactors at less than 3%.

Concluding comments

The role of South African business in contributing to land reform was outlined here as central to a land reform programme that is characterised as a “state incentivised, but private sector delivered” or “decentralised, but state enabled” process of land redistribution.

Included in this private sector delivery mechanism, and a substantive part of the fast-track process, is the important element of voluntary contributions of land, time, finance, inputs and skills by the farmers, businesses and urban elites that benefited from our unjust past.

In essence, this is a call for land (and capital, skills, and expertise) to be donated in the interest of inclusive economic growth and improved equity in land ownership and economic opportunity.

If taken up with good intent by the private sector, and with the necessary checks and balances in place, it should not be captured by the political or urban elite, but will empower all aspirant farmers and businesses — from the very small to the larger commercial entrepreneurs. DM

Professor Johann Kirsten is director, Bureau for Economic Research, and Professor Nick Vink is chair of the Department of Agricultural Economics, both at the University of Stellenbosch.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider