2019 ELECTIONS

Human rights in foreign policy: The rhetoric versus the reality

South Africa’s four biggest political parties all claim to advocate human rights in their foreign policies. But do they practise what they preach?

Foreign policy rarely figures prominently in any political election campaign anywhere. And that has also been true of the campaigning over the past few months for Wednesday’s parliamentary and provincial elections in South Africa. Some parties have not even bothered to mention foreign policy in their election manifestos.

Nonetheless, foreign policy is important because foreign relations are important, especially in a globalised world.

South Africa’s foreign policy clearly impacts on the lives of all South Africans, not least because it shapes the perceptions of foreign investors and others about this country, for better or worse. We are judged, to a degree, by our friends.

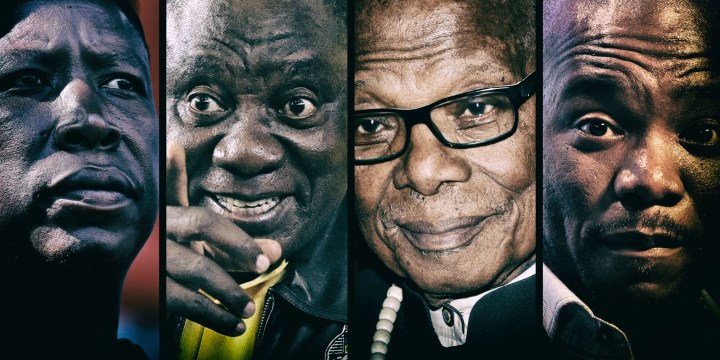

The four biggest political parties contesting for power on 8 May 2019 — the governing ANC, the chief opposition DA, the EFF and the IFP — have markedly different foreign policies in many areas, often reflecting differences in their domestic positions. However, they also agree on quite a few issues.

The ANC aligns itself, broadly, with the “global South” — the developing world — and especially Africa, and with “progressive” forces beyond.

This solidarity had given the South an influential voice on the world stage, said Febe Potgieter-Gqubule, former ambassador to Poland, former deputy chief of staff to the African Union Commissioner and now ANC general manager, at a recent seminar in Durban organised by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (foundation) (FES) and the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN).

Potgieter-Gqubule cited the example of how the South had established the principle of “common, but differentiated responsibilities” in the global climate change negotiations. This principle accepted that all countries shared the responsibility of tackling climate change, but developed countries had to contribute more because they had caused more global warming.

She stressed, though, that helping build stronger institutions of South to South co-operation did not mean the ANC was against co-operation with the “North” — the developed world.

“We can multitask … we are all part of a global village,” she said.

As its election manifesto shows, the ANC puts a lot of emphasis on respect for national sovereignty.

By contrast, DA MP Sandy Kalyan, a member of Parliament’s International Relations Committee for 10 years, told the same seminar that the core of liberal policy was the individual — and so respect for individual rights and freedoms underpinned the DA’s foreign policy.

These values evidently override national sovereignty as the DA manifesto promises:

“We will seek to build the pillars of a just society everywhere — to promote democratic governments and states characterised by accountable institutions, independent judiciaries, free media and vibrant civil societies.”

In other ways, though, the DA is less inclined to interference, pragmatically prioritising the “country’s economic and security interests” over ideological solidarity.

The EFF, unsurprisingly, has a more radical approach than the other parties, outflanking the ANC on its left by focusing its foreign policy on countering the West’s “global imperialist dominance” and forging alliances with like-minded progressive countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa.

Though it omits foreign policy from its election manifesto, the IFP’s foreign posture, as articulated by former MP Alfred Mpontshane at the FES/UKZN seminar, is founded on non-interference in the internal affairs of other states. He boasted that the IFP had been the most consistent advocate of this policy as it had begun by opposing disinvestment even from apartheid South Africa because, it said, this would hurt the poor.

Like the DA, International Relations and Co-operation Minister Lindiwe Sisulu frequently insists that human rights are at the heart of the ANC’s — and South Africa’s — foreign policy.

The EFF and IFP have also indicated as much.

Supporting human rights is a bit like advocating mother love and apple pie, though. No sensible political party would openly oppose it.

The true test is action. And so at the FES/UKZN seminar DA MP Kalyan asked if the ANC really did respect human rights. Why had it not, for instance, condemned the recent sentencing by its ally Iran, of Iranian human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh to 38 years in prison and 148 lashes for defending other women who had protested against the Iranian government forcing women to wear headscarves?

Kalyan also boasted that it was only because she and the DA had raised the issue in Parliament in 2018 that Sisulu had reversed SA’s policy and supported a UN General Assembly Resolution condemning the Myanmar government for its treatment of the Rohingya minority.

Whether or not the DA deserves the credit, this was a noteworthy change in the foreign policy of the Ramaphosa ANC versus the Zuma ANC.

This shift towards a more human rights-oriented policy is also apparent in the ANC’s present ambivalent stance on the International Criminal Court (ICC) The Zuma ANC had, late in 2017, introduced legislation to pull South Africa out of The Hague-based court (mainly because of its squabble with the court over Omar al-Bashir). But Sisulu has since stated that the governing party is now reconsidering that decision.

This is an issue which has apparently been kicked down the road, to be resolved after the elections because it is so divisive. And so, as UKZN researcher Lukhona Mnguni pointed out at the FES/UKZN seminar, the ICC was not even in the ANC election manifesto.

Potgieter-Gqubule said the African Union and SA had been correct to doubt the ICC’s even-handedness. She said, for example, that the US was very quick to send countries to the ICC. Yet it was written into US policy that if any US soldier was arrested and taken to The Hague, the US could “storm” The Hague to free that soldier.

She also referred to ANC policy that Africa should itself prosecute the gravest international crimes which the ICC now litigates — namely genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and aggression. She noted that in 2014 the AU had adopted a resolution to give the African Court for Human and Peoples Rights this jurisdiction. However, five years later, only three of the AU’s 55 member states had even signed the protocol, let alone ratified it, so it had not come into force, she noted, adding that SA was one of the countries which had not ratified the Malabo Protocol.

If Sisulu’s view about the ICC prevails, though, and the ANC finally decides after the elections to stay in the ICC and try to amend it from within, the party will have moved closer to both the DA and EFF.

The DA showed its strong backing for the ICC by recently asking the court’s prosecutor to investigate alleged human rights abuses of civilian protesters by Zimbabwe military and police.

The EFF supports the ICC in principle, according to its manifesto, but insists the court should undergo major transformation by making membership compulsory for all states. Big powers such as the US, Russia and China have elected not to join. The EFF believes a transformed ICC should prosecute “warlords like George Bush and Tony Blair”, presumably for invading Iraq in 2003.

A human rights-based foreign policy, if implemented, does inevitably collide at some point with the principle of national sovereignty.

And a country or party’s position on whether to interfere in the internal affairs of another often depends on its own friendship or enmity with the foreign state involved. This is illustrated by the famous, though apocryphal, the remark by US President Franklin D Roosevelt in 1939 that the nasty Nicaraguan dictator Somoza “may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch”.

All of South Africa’s main political parties undoubtedly have their own sons-of-bitches.

Mpontshane boasted at the seminar that the IFP was the most consistent of the SA parties in opposing interference in other countries’ internal affairs. He cited, for instance, the IFP’s strong opposition to past attempts (by the ANC’s tripartite alliance partner Cosatu), to force King Mswati III to democratise Eswatini (formerly Swaziland) through economic blockades.

He jibed at the ANC and others (implicitly the EFF) who now so vocally opposed sanctions against Zimbabwe, saying they were “born-again” to the cause of non-interference.

However, he also claimed the IFP was more ideologically consistent than the ANC because it not only supported the independence cause of Palestine, but also that of Taiwan.

The ANC would no doubt join its close ally China in regarding the latter as a flagrant interference in China’s “internal” affairs, since both regard Taiwan as a mere renegade province of China.

By its actions in visiting Taiwan, the DA manifests the same policy towards this issue as the IFP. And both have also criticised the ANC government for kowtowing to Beijing by not allowing the exiled Tibetan leader the Dalai Lama to visit SA.

The IFP is not alone in suggesting that the ANC has been inconsistent in its application of the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries. Others have also noted that the ANC had called on the world to interfere vigorously in the internal affairs of apartheid SA with sanctions. Yet now it opposes sanctions in Zimbabwe because these are hurting the poor.

Potgieter-Gqubule replied at the seminar that the ANC had resorted to calls for sanctions and isolation of SA in the 1950s and 1960s only after exhausting all peaceful means of change by persuasion, such as petitions and strikes.

So in general, peaceful persuasion should be tried before resorting to punitive measures such as sanctions.

SA supported the AU and SADC’s approach to intervention, by “engaging all sides”. She cited SA and SADC’s interventions in the crises in Madagascar, Zimbabwe, Lesotho and Cote d’Ivoire as evidence for this approach.

She also defended the ANC’s policy decision to downgrade SA’s embassy in Israel to a mere liaison office on the grounds that Pretoria had exhausted all efforts to persuade Israel to end its occupation of Palestine territory.

The DA, too, has criticised Israeli settlements on the West Bank. But it also opposes the downgrade of the SA embassy, believing it will harm SA’s trade and investment with Israel and also its ability to be an honest broker in the dispute between Israel and Palestine.

The ANC, DA and IFP all nonetheless support a two-state solution, with independent states of Israel and Palestine existing side by side in peace.

The EFF is the outlier, believing a two-state solution is no longer possible given the extent of Israel’s expropriation of Palestine land. It believes Israel should be returned to the Palestinians. It also wants a full boycott of Israeli products and for the embassies in both countries to be shut down.

All four of these parties oppose what seems like threatened US military intervention in Venezuela, though they differ in many other aspects of that crisis.

Potgieter-Gqubule said Pretoria was strongly supporting President Nicolas Maduro’s government against what she called US “imperialism” in Venezuela and elsewhere in South America.

The EFF is more fiercely opposed to any outside interference in Venezuela, for the same reason and because it likes Maduro’s socialist policies.

Both the ANC and EFF have stated they believe it is US sanctions which have crippled the Venezuelan economy, while the DA blames Maduro’s own policies for impoverishing his people.

The Zimbabwe crisis also highlights sharp differences among South African political parties.

The ANC has strongly opposed Western sanctions against Harare and has called for them to be lifted as a first step towards reconstructing the economy.

The DA believes that the ruling Zanu-PF party itself is responsible for the country’s economic collapse, because of its own ruinous policies, starting with the seizure of productive white farms.

The IFP, as Mpontshane noted, also opposes outside interference in Zimbabwe.

The EFF also opposes Western economic sanctions against Zimbabwe — because it likes Zanu-PF policies, especially its seizure and nationalisation of white farmland. Yet it has also called for intervention by South Africa against human rights abuses committed by the Zimbabwean military and police forces against civilians.

All four of the parties have expressed support for Western Sahara’s campaign for independence from Morocco.

One can, however, detect Rooseveltian elements in the way all these parties select some countries for sanctions and not others.

The EFF strongly opposes Western economic sanctions against Zimbabwe, but equally strongly advocates outside interference to topple the BDP government in Botswana because it regards it as a military ally of the US.

All four parties favour African solidarity in economic terms, however, backing economic integration initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Agreement, which is in the process of being implemented.

Potgieter-Gqubule probably spoke for all when she said the regeneration of Africa was an essential part of ANC foreign policy.

However, it is also clear that undocumented immigration is the awkward point where the ideal of African solidarity clashes with economic and social reality and with election politics.

All the parties have expressed the need for greater control of the large influx of foreign nationals — almost all African — into South Africa.

These policy stances — and the occasional outbreaks of xenophobic — which some have called “Afrophobic” — violence, have clearly harmed relations with other African countries.

As UKZN’s Mnguni pointed out, the positions of the political parties have mostly hardened on immigration.

In its 2019 election manifesto, for instance, the ANC promises to protect locals participating in the local economy by expanding “the campaign to stop illegal trading in townships and villages, much of which is conducted by foreign nationals …”

“This seems a strong departure from the party’s position in 2009, where it called for a need for South Africans to acknowledge the contribution of foreign nationals in the economy,” Mnguni noted.

Potgieter-Gqubule said that SA needed to debate the issue and figure out what to do about it.

She noted that one of the reasons the ANC had since 1994 argued for SA to play a large role in peace efforts on the continent was to try to ensure peace and therefore development, so that people could peacefully live in their own countries.

The ANC was also addressing the problem of porous borders through plans to create a dedicated Border Security Agency to deal with all aspects of border security.

Mnguni noted that the word “borders” featured 16 times in the DA’s 2019 manifesto and the phrase “securing our borders” had even made it on to electioneering posters of the party.

Kalyan insisted at the seminar that the DA was not anti-immigrant, but that undocumented entrants were straining public services. “ We need foreign nationals with scarce skills. We welcome them. But they must come in the right way.”

The IFP’s Mpontshane said his party believed in economic co-operation with Africa, but opposed uncontrolled entry of foreigners into SA.

Mnguni noted that the EFF, again the odd man out, approached immigration instead from its pan-Africanist perspective, dismissing Africa’s national borders as a chronic impediment to Africa’s development and promising that an EFF government “will fight for a borderless Africa and a single currency in the medium to long term”.

All four of these South African political parties support Brics — the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa forum, though to different degrees.

All believe it can bring economic benefit to South Africa, especially through its New Development Bank which has already dispensed some US$2-billion in loans to SA.

The ANC and EFF also regard Brics as beneficial in ideological terms, as a counterweight to Western dominance of international institutions of political and economic governance, such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

The DA has expressed concern that this orientation should not harm SA’s relations with the “North” or West, noting that these are still vitally important to the economy.

However, as noted, Potgieter-Gqubule has stressed that the ANC’s emphasis on South-to-South relations does not mean in any way that it is opposed to good relations with the North.

The capabilities of South Africa’s diplomats is also a political issue. At the Durban seminar, Kalyan stressed the DA’s key role in getting the new Foreign Service Bill passed through Parliament in 2018. Since the advent of democracy in 1994 the foreign service had operated on an ad hoc basis using favouritism in appointments, and indulgence of incompetence, corruption and indiscipline by many of the country’s diplomats.

South Africa now had 125 foreign diplomatic missions, each staffed by about 30 people. The number of missions clearly needed to be reduced, with more embassies covering more than one country. The bill would help to achieve all of this, including by setting clear objective criteria for the appointment of all diplomats, she said.

Potgieter-Gqubule partly agreed, but also defended the ANC government’s decision to open an embassy in every African country, “because we believe Africa is the mainstay of our foreign policy”. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider