BUSINESS MAVERICK

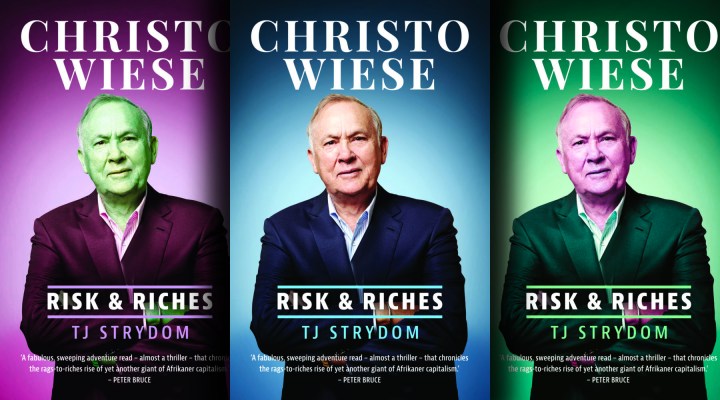

Book Extract: Christo Wiese – Risk and Riches

In this extract from Christo Wiese – Risk and Riches, Wiese is told about the accounting problems at Steinhoff that started the collapse of the company’s share price – and the unravelling of his life’s work.

Only a few days before the shares were issued, the news agency Reuters interviewed Christo Wiese. Two experienced journalists quizzed him on the chances of a Steinhoff-Shoprite merger. Giving nothing away, he said that to combine the two companies would be “a natural development”.

“People know that I am 75 years old, and I, fortunately, have a son who is in business with me, but as a family, we are continually looking at consolidating our business interests,” he added.

The story hit the wire and within minutes the share prices of both Shoprite and Steinhoff rose sharply – the market read it as a sign that a transaction was looming. Afterwards, Wiese was not happy about the story, probably because he and Markus Jooste were already planning a wedding between the two companies.

Three months later Steinhoff and Shoprite announced that they were in talks to form an “African retail champion”. Shoprite, at this stage, was a retail giant. It had managed to achieve something special – it owned hundreds of supermarkets in African countries that companies usually shied away from. In many of these markets, there was hardly any formal retail before Shoprite’s arrival, so it could create the market and then dominate it, with plenty of room for future growth.

It also had a strong foundation in South Africa where its share of the market was more than a third with its Shoprite, Checkers and U-Save stores. The company had digested its three life-changing acquisitions in the 1990s – Grand Bazaars, Checkers and OK Bazaars – without any reflux and had used the time since then to make its systems and warehouses more effective than those of its local competitors.

What is more, its market share was growing as low-income consumers rushed to Shoprite to get more bang for their buck in an economy with high unemployment, glaring poverty and weak prospects. Those with more to spend increasingly shopped at Checkers as it made a play for the lucrative business that Woolworths had developed as an upmarket grocer.

One dominating factor ensured Shoprite’s success – Whitey Basson. Wiese and Basson had been friends for five decades and knew each other through and through. By this time their sons were serving on Shoprite’s board with them. “The milestones we have achieved were mostly of his doing – the decision to move into Africa against some very fierce opposition at the time, the introduction of the one-stop shopping concept with the maximum number of services offered under one roof, taking control of our own distribution, and creating the infrastructure to do so,” said Wiese a few years earlier.

Basson, in turn, said the business was able to grow because Wiese, as chairman and controlling shareholder, gave him the freedom to do what needed to be done.

By this time Basson was retail’s elder statesman. In South Africa, with its wide gap between rich and poor, his remuneration was still a topic of much interest in the media. Usually, trade unions complained in the press about the plight of their members while the chief executive took home a fortune. “I would pay R1-billion in the middle of the night for another Whitey,” said Wiese. “Who else could have built a company we bought for R1-million into a company worth over R100-billion today?’

By the end of 2016, Basson was 70 years old. He and Wiese regularly fielded questions about when they intended to retire or what sort of succession planning Shoprite was doing for the day that Basson would no longer be in charge. “Whitey suffers from an ailment that I think I also suffer from, to some extent. A belief that we will live forever,” said Wiese.

Shortly after his old friend told the media that combining Steinhoff and Shoprite would be a “natural development” and only a month before the transaction was announced, Basson retired. Both he and Wiese said the planned transaction between Steinhoff and Shoprite was not the reason for his decision.

Basson said he was just tired of all the red tape that had become part of retail. “The stress of running a big business is massive, I’m constantly fighting on several fronts,” he commented.

But soon it became clear that Basson was not willing to put his thoroughbred in Steinhoff’s stable.

The plan was to have Shoprite buy all Steinhoff’s interests in Africa, paying with Shoprite shares. The result would be that Steinhoff took control of Shoprite. The deal would put Pep, Ackermans, Dunns, JD Group’s furniture stores, building-material suppliers such as Pennypinchers and the shoe chain Tekkie Town all under Shoprite’s umbrella – and with the name New Retail.

Wiese had the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), which manages the retirement funds of civil servants, on his side. Like Wiese, the PIC was a big shareholder in both Shoprite and Steinhoff. The PIC also liked the idea of an “African champion’.

Minority shareholders were not at all on board. Investors prefer to know what they are investing in. Shoes, celery, spades and sofas wouldn’t necessarily work in the same company. Different factors could influence consumer sentiment for the various goods. Asset managers with Shoprite shares also complained that the announcements did not explain the planned transaction in enough detail. They saw too little evidence of clear cost savings in the new group and feared that shares with great potential would be swapped for a stake in an inferior business.

Basson shared the views of the minority shareholders. He said in an interview that Steinhoff simply did not look like a good business as its return was too low and its debt too high. “Yes, I was against the business. There were no synergy benefits in it,” he said. He also did not see how the groups were supposed to fit together. “What would you benefit by putting Anglo American and Toyota together?”

Eventually, the parties abandoned the negotiations after they could not agree on a price – how many Steinhoff shares had to be swapped for Shoprite shares. Jooste said that in the end Steinhoff did not want a 100% stake in Shoprite and gave up on the merger talks. “He took it, he was not upset,” he said about Wiese’s reaction.

After the transaction, a journalist asked Basson whether he was happy that the transaction did not go through. “Are you asking if the Pope is Catholic? Well, he is!”

Maybe not even the Pope would have been able to resolve the conflict then raging between the two factions of the ruling party in South Africa. President Zuma and his loudest supporters seemed to be at war with finance minister Gordhan and the national treasury. “That is a very, very unfortunate impression. Very unfortunate. But we keep on saying that. And we say it openly and very robustly,” said Wiese, while many business leaders tiptoed around the issue.

Mcebisi Jonas, Gordhan’s deputy, revealed early the previous year that he had been offered a very generous remuneration package – a fortune – to become minister of finance. And it was not his boss, Zuma, who allegedly made him the offer, but the Gupta family, friends of the president and infamous business people in South Africa. Jonas called it a case of “state capture”.

In the following months, these words became the chorus line in reporting about government, especially when the president or some of his ministers acted unpredictably.

Eventually, despite pleas by business leaders and the danger of a junk credit rating, Zuma shuffled Gordhan out of the cabinet in March 2017. Within days, two of the big three credit-ratings agencies downgraded South Africa’s debt to sub-investment grade. The value of the rand fell.

No matter what the country’s status, Shoprite remained a bluechip stock. But by this time it was clear that another Steinhoff deal was brewing. Basson voted with his feet.

Over the years he had built up a tidy stake of about 1,5% in Shoprite. Upon his retirement, the company bought back all his shares from him at a slight discount. He said the decision to sell was not directly the result of the possible deal and that he had simply exercised a selling option. Basson, who had built the company into a continental giant, was nevertheless willing to let his shares go for a lower price than the market value. Shoprite paid him R1,75-billion for his stake – not bad for a pensioner.

This was also a boost for Steinhoff’s plan to gain control of the retailer, as the shares were bought back by the company and did not go into another investor’s pocket.

Firstly, Steinhoff put all the retail assets it wanted to merge with Shoprite in a separate company called Steinhoff Africa Retail (STAR). Then it listed this entity on the JSE – the biggest part of its value lay in the “old” Pepkor. STAR, of course, was still controlled by Steinhoff International.

At the same time, Steinhoff announced that it would acquire, through its subsidiary STAR, as much as 23% of Shoprite, buying it from the Wiese family, the PIC and the empowerment partner Lancaster. But more importantly, the company would buy a block of shares from Wiese that carried more voting rights

than those of the ordinary shareholders. And so STAR would hold more than 50% of the votes, giving it effective control over Shoprite.

Because Basson’s shares had been bought back and cancelled, STAR’s stake remained just below the threshold that would have forced it to make an offer to all the minority shareholders. The transaction was valued at R35,5-billion.

When asset managers criticised the planned transaction, Wiese insisted that STAR’s listing had no effect on Shoprite shareholders. “They are in exactly the same position post-STAR as they were before STAR.” And Shoprite would continue as before, with its own plans and strategy, he added.

But other events conspired to disrupt this silent takeover manoeuvre. Just a few days before STAR’s listing on the JSE, Jooste and Steinhoff’s chief financial officer, Ben la Grange, received an email from Deloitte. As auditors, they had been given information about the German tax investigation and certain negative media articles about Steinhoff had also come to their attention, the email read. Deloitte wanted Steinhoff to comment on the accusations and said that in the light of the allegations, additional audit procedures would need to be followed, Jooste later recalled in parliament.

A few days later, Steinhoff met the auditors in Stellenbosch where the management explained that the investigation it had commissioned two years earlier would be available soon.

After a few more days, Deloitte addressed a letter to Steve Booysen, head of Steinhoff’s audit committee. The letter referred to the allegations. It was a mouthful: non-compliance with tax planning, and (wait for it …) the potentially incorrect application of accounting principles specifically identified as revenue recognition and transactions with related parties. Deloitte requested a detailed report on the matter. Jooste recalled later that he and Booysen answered Deloitte, saying that the allegations were not new. They added that the firms they had appointed would have a report ready soon.

Less than two months later the firms sent a “huge document” to Deloitte dealing with “every issue and every query raised”.

They had reviewed in excess of 15,000 documents and all contracts and email communications between Steinhoff executives, as well as conducting interviews with Steinhoff personnel and parties involved in all the relevant countries, according to Jooste. They had also met with the authorities several times.

But Deloitte wanted more information and wished to conduct more tests. They were of the view that a brand-new investigation should be started, because they were not convinced by the firms Steinhoff had appointed.

Meanwhile, the news agency Reuters revealed in an investigative piece that Steinhoff had kept its shareholders in the dark about transactions to the tune of $1-billion (more than R14-billion) with a related company – this despite European laws that experts believed compelled the company to inform shareholders.

It was back and forth between the auditors and Steinhoff.

Wiese attended some of the meetings, as did Booysen. According to Jooste, Deloitte at one stage agreed that another investigation was not needed, but then changed its mind.

At stake was whether Deloitte would sign off Steinhoff’s financial results, which were scheduled to be released on Wednesday, 6 December. By then it was late November.

The first weekend of December, Jooste was in Germany to attend Bruno Steinhoff’s 80th birthday celebrations. By the Monday he was back in Cape Town. He called Wiese from the airport. He had the documents needed to get the results finalised and signed off, and said the auditors could come in for a meeting, Wiese recalled later.

But Jooste did not pitch. “And then I feared the worst.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider