OP-ED

Eskom and the deepening water crisis in South Africa

The connection between water and energy in a water-scarce country like South Africa is huge, because moving and purifying water needs a lot of energy, and in order to generate energy a lot of water is required.

In order to understand the impact that Eskom is having on the water situation in South Africa, it is first necessary to understand the water-energy nexus. In its simplest form, the principle of the nexus acknowledges the link between energy and water. This promotes an understanding that to move and purify water requires a tremendous amount of energy, and by the same token to generate energy you require a large amount of water.

This means in a water scarce country such as South Africa the management of water and energy should be done in an integrated fashion. To better understand the impact of Eskom’s failed monopoly of the energy market on the water situation in South Africa and the economy as a whole, it is useful to answer a few questions.

Does water scarcity impact the GDP and local economy?

In short, yes. There is a strong body of literature which confirms the negative impact that drought or water scarcity has on the economy of a country (Brown et al, 2010; McKinley, 2009; World Bank, 2005; FEMA, 1995; Benson C and Clay E, 1994; Pretorius c and Smal M, 1992). Impacts range from direct links such as reduced agricultural production to more subtle impacts such as delays in industrial production processes, increased water treatment costs, and disruptions in energy production.

The 2015 Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) water disclosure report showed a drought impact of R610-million estimated by just 10 companies relating to the 2015/2016 water scarcity situation which developed in the Vaal catchment in 2016 (CDP Water Infographic, 2016).

Figure 1: Financial impact of 2015/2016 drought on 10 companies in South Africa (CDP Water Infographic, 2016)

Time will reveal the full economic impact of the recent drought in the Western Cape which was far more severe.

Is the current energy situation impacting water security in South Africa?

Again, the answer is yes. As is already mentioned, energy is required to pump and treat water. This situation can result in a water deficit at a municipal level as treatment plants cannot be run effectively and water cannot be pumped to fill up key supply reservoirs in the municipal supply network. This means that supply may not be kept at the levels required for continued delivery of water with disruptions occurring in various areas.

A longer-term problem could occur at a bulk water supply level. Cities in South Africa have been established around mineral deposits due to mining development rather than in close proximity to water resources as has occurred in many other countries around the world. This, coupled with high rainfall and runoff variability has resulted in massive engineering infrastructure (designed to move water efficiently around South Africa, to high-use areas, but reliant on power) required to move water from areas of plenty to areas of deficit and ensure water security for places like Gauteng.

In terms of the Vaal system, three of the four major augmentation options are pumped storage schemes, namely: the Usutu Vaal Link Government Water Scheme (GWS) supplying 6 m3s-1 at 374 m up the escarpment; the Slang River (GWS) supply capability of 3.3 m3s-1 and the Tugela Vaal Link GWS which can supply an average of 18 m3s-1 (this can be transferred at a rate of 218 m3s-1 but it is limited by the canal capacity) up the 452 m. All water transfer information from “Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment” ORASECOM (Jeleni A, Mare H; 2007).

Figure 2: Major transfer schemes into the Vaal Catchment (Map EkoSource GIS Department)

Similar transfer schemes pump water from Nooitgedacht and Vygeboom dam scheme in Mpumalanga as well as the Berg River Theewaterskloof dam scheme in the Western Cape.

The main issue relating to these schemes is that their capacity is not high enough to supply water for the demands of users in those areas. The consequence is that to ensure supply continuity pumping thus needs to be done over longer periods. Presently, in the case of the Vaal system, with low levels in the Lesotho Highlands, pumping should be taking place to ensure supply continuity in the Vaal system (the main source for Gauteng, Africa’s economic hub) and have the necessary buffer storage to ensure supply continuity.

Load shedding can prevent these major transfers from happening, thus affecting water security in the Gauteng area. Similarly, pumping from Berg River dam to Theewaterskloof in the Western Cape should be taking place because there is a strong possibility the Berg River dam could overtop (meaning – overflow, with associated waste) and be lost to the system. Similarly, power restrictions could be hampering the transfer of water in this scheme.

Finally, a double impact could occur in the case of the Nooitgedacht scheme because water is required to ensure energy production is maintained in the Olifants catchment: if water is not pumped it could affect water supply to a large number of power stations in that region.

In addition, there are several pumped storage water schemes in South Africa where water is pumped up and stored to be used as a “giant battery” when required. These schemes use surplus from the energy grid baseload during the day and then release water at a later time when demand peaks. Low production levels reduce this ability and result in the requirement to use expensive diesel-fed open cycle gas turbine generators to make up for the energy deficit.

What is the current water situation in South Africa?

Analysis from the Department of Water and Sanitation’s National Integrated Water Information System (NIWIS) reveals some insight into the current water situation.

From a national perspective, the major dam storage facilities are in the low category, meaning that, historically, 75% of the time our major dam water resources have been higher than the levels at which they are presently. However, more concerning is the situation relating to the Vaal where the Vaal dam is at 70% – but this is in the low category being 13% lower than last year at the same time. It is also lower than the beginning of the 2015/2016 drought with little prospect of any late-season rainfall to fill dams.

Figure 3. Vaal Dam level at 2015 compared to present before the 2-year 2015/2016 drought started. (NIWIS, 2019)

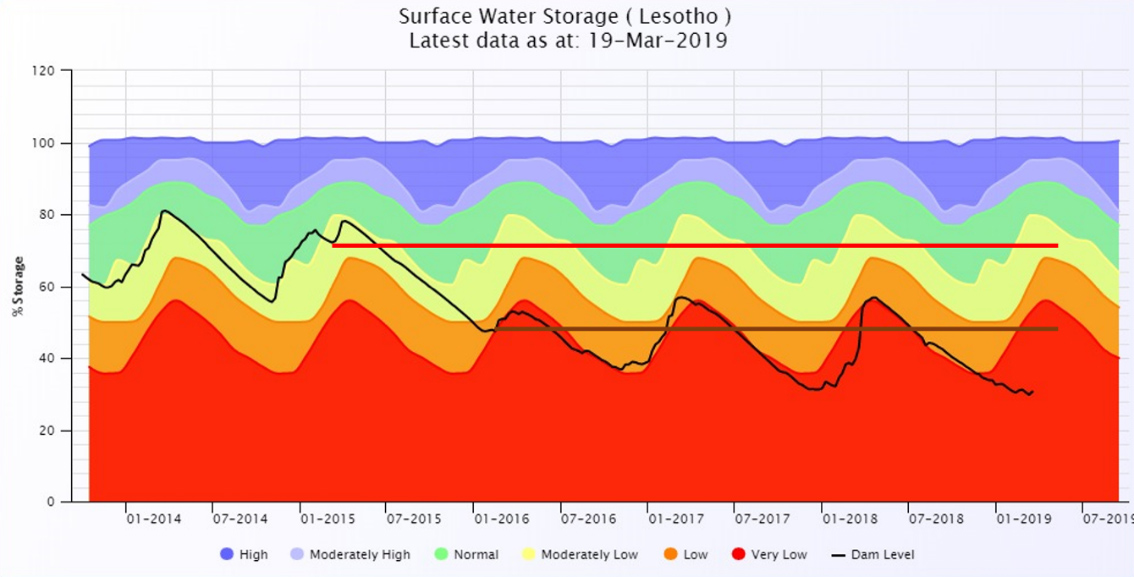

In addition, the supplementary supply to the system is significantly lower than previous years with the Lesotho dams (Katse and Mohale) and Sterkfontein Dam being at significantly lower levels than at the beginning of the previous drought, meaning that the back-up required to support the Vaal system is simply not there.

Figure 4: Lesotho dam levels at the beginning of 2015 and 2016 compared to current levels (NIWIS, 2019)

So, while the Cape town crisis may be over at present, there are many areas in the country that could potentially be in difficulty, especially as we are going into the dry season. Dam levels in four of the nine provinces are at low levels, while the five other provinces are considered at moderately low levels. The inability to pump and move water on the major supply schemes due to electricity constraints will reduce water managers’ flexibility to improve water scarcity in various regions.

Is Eskom’s approach to renewables potentially impacting longer-term water security?

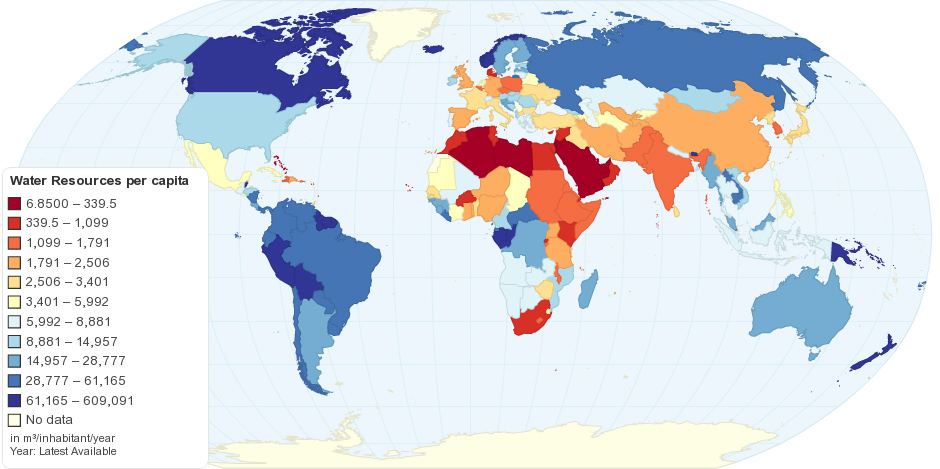

South Africa has one of the lowest levels of water availability per capita in the world. Thus South Africa is a water-limited economy.

Figure 5: Water Resources per Capita, (Aquastat 2010).

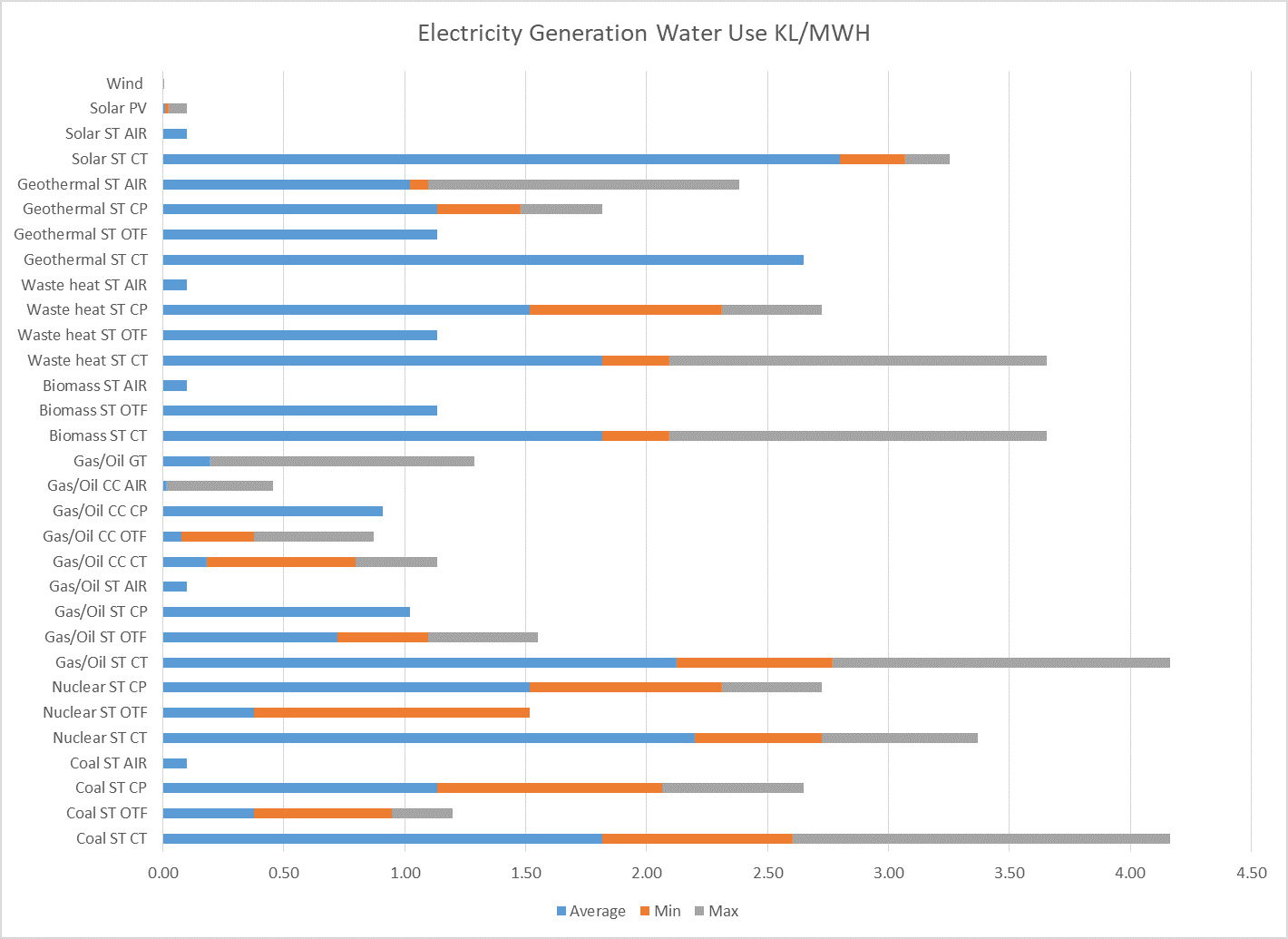

The situation is unlikely to improve because the majority of climate change predictions show a hotter, drier climate with more variability. It is from this perspective that, strategically, the country should be shifting to the most water-efficient power-generation technologies available. Currently, wind and photovoltaic power generation are the most water-efficient technologies available. Water use by either of these power-generation technologies is a fraction of even the most efficient dry-cooled coal or nuclear production available which still use steam turbines for energy production.

Figure 6: Water use by different power generation technologies (Spang et al, 2014)

Unfortunately, the current dispensation with overregulation by NERSA and Eskom monopolising the energy market by its control over the transmission grid has led to a low uptake of renewable energy.

A proclivity for large energy generation projects with restrictive bidding requirements to become Independent Power Producers (IPPs) has stifled the energy market. This makes bidding a high risk and expensive process resulting in high prices for energy onto the grid.

The result is a low number of large renewable-energy generation projects and limited uptake of water-efficient renewable technologies. There is undoubtedly a need to add further wind and solar projects to the energy grid to take pressure off Eskom’s current power generation capacity. This will allow for good maintenance and even the retrofit of less water-intensive cooling technologies on current coal-fired power generation

Will the energy-water scenario in the country improve?

It is hoped that by the proposed separation of power generation from the transmission grid that a more competitive energy market will develop where smaller renewable projects can begin to produce energy onto the grid. It is likely that a lot of these will be smaller scale photovoltaic solar projects and encompass wind into the mix.

It could also open the market in areas where water-energy potential is not being used. There are only two hydroelectric dams in South Africa; however, there are a large number of dams where water is released almost continuously without any hydropower on them.

The hydropower potential, even though each individual scheme is small, collectively represents a significant resource and should be utilised. This could further reduce the power generation load from existing facilities. Hopefully, this will produce a shift away from the water expensive technologies and ensure unused existing power potential assets in South Africa.

These systems may allow the opportunity for better maintenance of existing facilities and perhaps the retrofitting of older power stations with more water-efficient technologies. The proposed splitting of transmission from generation opens up the energy market and should encourage a shift to renewable technologies. The main proviso being that the sector is deregulated with less stringent controls that could hamper the market and that all South Africans are allowed to sell to the grid, as happens in many European countries.

What strategy should South Africa adopt to ensure it can reduce both energy and water scarcity in the future?

A number of practical steps could be taken to ensure a better water and energy future.

-

Separate power generation from transmission, allowing the transmission network to purchase generation from any energy producer.

-

Deregulate the energy market, allowing for more competition.

-

Encourage the development of water-efficient power production technologies such as wind and photovoltaic solar.

-

Set up facilities which use the un-utilised power potential, i.e. dams releasing water to downstream irrigators or users, pipes in areas where pressure needs to be reduced to name a few.

-

Retrofit power stations with more water efficient technologies.

-

Encourage reduced water use in urban areas to reduce water treatment and water pumping requirements.

-

Set up waste to energy waste-water treatment plants.

-

Treat waste water back to potable standard which can reduce bulk water pumping requirements.

-

Investigate more efficient treatment technologies to reduce chemical and electrical requirements. These are available, but not currently utilised.

-

Public-private partnerships to ensure South Africa is well-resourced in the water and energy sectors.

What can you as an individual do to improve the situation?

While individual impacts might not seem significant, the collective impacts can be substantial. As an individual household, you can adopt a water saving strategy. The good news is that these strategies generally have a direct payback within a few months to a year of the initial investment. The following list is in order of highest returns on investment to lowest.

Measure: Knowing your water consumption is a key first step. Most residential households have meters and taking a reading just before you go to sleep and again early in the morning can give you an indication of whether there is a leak or excessive water consumption. New water meters can be linked with the internet of things (IOT) to enable continuous monitoring and burst or leak detection.

Reduce: Fix leaks first. Many houses have unidentified water leaks and fixing them can reduce water use substantially.

Reduce: Put water saving technologies into your home. Many taps, toilets, showers and various household appliances can be retrofitted with water-saving technologies that reduce water use without affecting comfort. More efficient appliances can also be purchased, such as washing machines and dishwashers. Energy-efficient geysers are continually being improved.

Reduce: Plant a water-efficient garden.

Augment: Using rainwater harvesting for swimming pools and garden can substantially reduce municipal water requirements

Re-use: Take greywater from your bath or basin and use it in the garden. You can replumb the house for toilets to use grey water to flush but this is an expensive option.

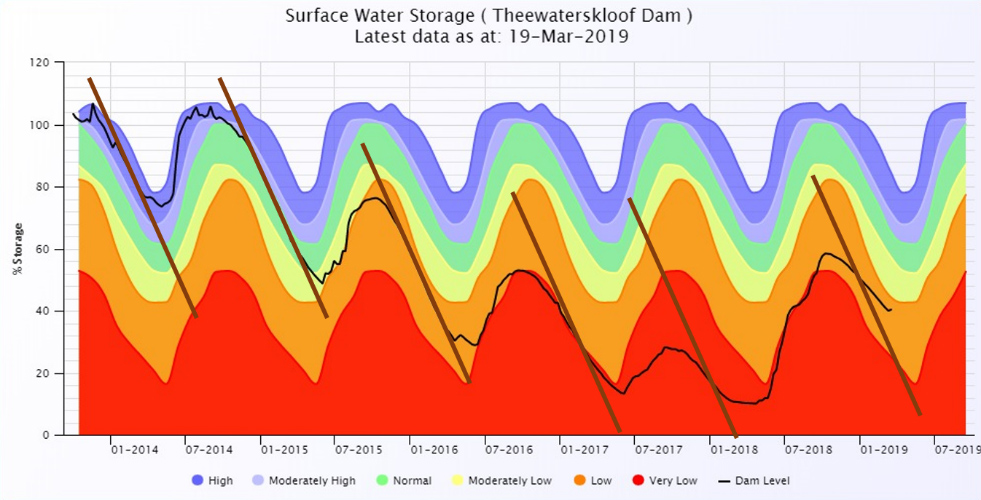

The cumulative effects of reduced water consumption can have a major impact on water security because it decreases the rate of emptying of municipal reservoirs as well as bulk water reservoirs, reducing the risk of depleting these facilities completely. This is well demonstrated in the Western Cape system where a change in gradient due to reduced consumption resulted in the prevention of complete reservoir failure and speeded up reservoir recovery. See figure of Theewaterskloof dam below.

Figure 7: Gradient lines comparing reservoir depletion rate of Theewaterskloof parallel lines show the 2015 depletion rate. (NIWIS, 2019)

It can be seen that reduced water use in 2017, 2018 and 2019 has created a shallower gradient and reduced depletion rate.

Additionally, the less water you use, the less energy is required to pump and treat it, leading to the added benefit of more energy for other activities. DM

Jason Hallowes is a hydrologist, entrepreneur, director and shareholder at EkoSource Insight, a water and energy consultancy and solution provider based in South Africa. He has 20 years of local and international experience in the water industry being a director of Clear Pure Water, managing director of DHI (Danish Hydraulic Institute) SADC branch and is currently with EkoSource Insight.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider