OP-ED

Happiness in a globalised world, and why it is important

The United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network released its annual World Happiness Report last week. Compiled since 2012, it provides an overview of happiness around the planet. While happiness might be a subjective category in our lives, this report indicates happiness is more complicated and politically consequential than we may realise.

Happiness is a difficult category to define. Ask a handful of people what makes them happy, and a handful of answers is likely to emerge. What makes people happy at one point in their lives might not be the case later. Happiness becomes even more complicated when contemplating what it means on a global scale. Life is complex and happiness, like other emotions, doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

These ambiguities are precisely why it’s important to think seriously about what constitutes happiness, how it can be categorised and measured, and how this information might lead to the development and implementation of policy frameworks aimed at not only cultivating, but also sustaining happiness.

Taking this into consideration, the World Happiness Report taps into the field of psychology devoted to the science of happiness. Drawing from measures of subjective well-being, a field of psychology that attempts to account for mood and life-assessments, it grapples with the distinction between cognitive life evaluations and emotional reports.

Cognitive life evaluations measure how happy an individual might be, based on an individual’s assessment of their life. Using the Cantril ladder, respondents were asked to rank the status of their life on a scale of 1-10. Alternatively, emotional reports are engaged with ranges of positive and negative affects. While life evaluations encourage one to reflect on whether their life makes them happy, an emotional report is more probing, asking one to consider what in their life makes (or doesn’t make) them happy.

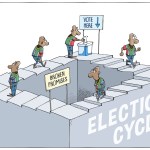

In the 2019 World Happiness Report, big data and well-being, prosocial behaviour, and how happiness correlates with voting behaviour are examined. One important conclusion about happiness and voting behaviour is that higher levels of happiness generally correlate to more active voters that are more likely to vote for incumbent parties, while unhappiness tends to mean people are less active.

In a country such as South Africa, which ranked 106 out of 156 countries, the ramifications of this finding are significant. Ahead of the 2019 general election, parties such as the Democratic Alliance and the Economic Freedom Fighters, among other smaller parties, seem likely to capitalise on the feelings of unhappiness throughout the country, which could mark a seismic shift in the development of South Africa’s democracy away from the African National Congress.

Additionally, the report builds on previous studies of global happiness from the Gallup World Poll between 2005-11, as well as its own data from 2012-18. In assessing the world rankings of happiness according to a country, the study relies on six variables to try to determine the significance of emotional reports and positive and negative affects. These variables are: GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy at birth, freedom to make life choices, generosity and absence of corruption.

Of the three worldwide samples that use Cantril’s ladder to assess happiness, the weighted and unweighted samples provide interesting results. In the weighted sample, which is made up of each country’s share of the total world population, happiness remains relatively stable, but trends downward. However, in the unweighted sample, which is made up of the average of individual national averages, happiness trends upward. As the study indicates, this contrast demonstrates recent upward trends have tended to be experienced in smaller countries, not those with large populations such as the United States, China and India.

Regional data on happiness presents a different picture. While there is no discernable trend in happiness using Cantril’s ladder in sub-Saharan Africa between 2005-18, the Middle East and North Africa have trended downward by nearly one full point. Similarly, in the Americas and Australia-New Zealand, happiness has also trended downward during the same period. In Western Europe, there is no discernable trend, whereas in central and eastern Europe, happiness has trended upward by more than 0.5 over the same period.

One point in happiness may not seem like a significant change. However, the difference between ranking one’s life as a five one year and six the following year, may mean moving from living paycheck-to-paycheck, towards saving for the future. Ranking one’s life as a six one year and a five the following year could also mean emerging support for populist parties that self-servingly tap into feelings of unhappiness.

When looking at regional trends of positive and negative affects in Africa, the results are even more interesting. In the Middle East and North Africa, positive affects have decreased, and negative affects have remained stable. Alternatively, while positive affects remain stable in Sub-Saharan Africa, negative affects have risen about one point from 2005-18, suggesting sub-Saharan Africa is becoming unhappier.

Like regional data that differs from global data, country-by-country data of sub-Saharan Africa tells another story. Since countries around the world don’t gather data equally on the six variables mentioned earlier, variations between countries aren’t apparent in the broader sets of global and regional happiness trends. For instance, over the 2005-18 period, the 28 countries that make up sub-Saharan Africa illustrated a wide range of happiness: 13 countries became significantly happier, while 10 became significantly unhappier.

Nevertheless, the question remains: What does it all mean? Venezuela’s happiness score, for instance, has dropped dramatically in recent years. In data gathered between 2010 and 2019, Venezuela dropped nearly one hundred places, from the 20th-happiest country in 2013, to 108 in 2019. Although the World Happiness Reports indicate people tend to rate their happiness consistently, examples like Venezuela suggest that happiness is a reactive, rather than proactive emotion.

Although we all experience happiness, we don’t share an understanding of what it means, especially on a global scale. What the 2019 World Happiness Report foregrounds is that a better grasp of happiness may help us to understand the changing dynamics of societies and political behaviour around the world. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider