Business Maverick

Jumia’s billion-dollar NYSE listing comes amid both good and worrying signs

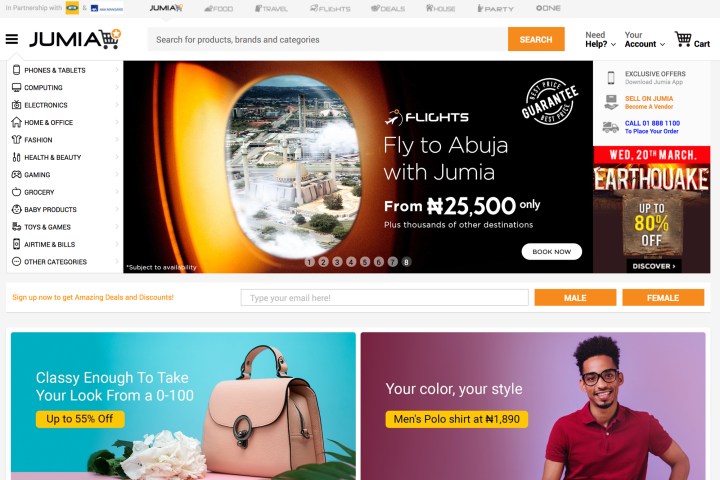

Later in 2019, the New York Stock Exchange will see the first listing of an African technology company to be valued at more than $1-billion, a real, actual dinkum unicorn. The company, Jumia, is Nigeria-based and is known as the African Amazon since it is primarily an e-commerce business. But is it a good investment?

African techies and “Africa Rising” enthusiasts are willing the NYSE listing of African “unicorn” Jumia to succeed, and hopes are high the listing will go off well. But if you read the company’s pre-listing statement, it does illustrate just how amazingly difficult it is to actually do e-commerce in Africa.

Jumia operates in 14 African countries and had four million customers and sales of about $149-million in 2018. This is a chunky rise from the $94-million in sales and 2.7 million customers it had 2017.

On the other hand, in a way typical of booming internet startups, the more customers it gets, the bigger it losses become; those slipped from €165.4-million in 2017 to €195.2-million in 2018.

Yet, the company is hoping to raise around $1.5bn on the listing, which is backed by everyone you can name, including Morgan Stanley, Citigroup, Berenberg and RBC Capital Markets. Goldman Sachs would normally be there, but they actually own part of the company. The other owners include a whole bunch of companies who have pumped money into the group over the past five years, including Millicom International Cellular, Orange, Africa Internet Group, a venture backed by Goldman, MTN and Rocket Internet.

This last group, Rocket Internet, is significant because they are generally looked on a bit askance in start-up circles. They were founded by some smart German ex-McKinsey entrepreneurs who decided on a business model based on simple copying. They would look out for anything that was working, and replicate it in geographical areas where that business didn’t exist.

So if Jumia looks a lot like an African Amazon, it’s no accident. Except that Jumia has been morphing and innovating in interesting ways; it’s much more business-to-business (B-to-B) than Amazon, whose e-commerce business is more business to consumer (B-to-C). Its become more of a platform than a seller in its own right, on the model of Chinese giant Alibaba. It now has 40,000 active vendors on the platform across Africa. Jumia has branched out into insurance sales and financing — things it can do without having to actually deliver goods.

And reading the recently released US Securities and Exchange Commission F-1 listing documents, you can understand why. These documents should be taken with a pinch of salt because they are always massively cautionary, basically in order to prevent investors from suing if the listing flops. Hence, every warning under the sun is issued, including the warning that the company might never actually make money.

The biggest problem for African online e-commerce is that credit cards are a rare commodity on the continent. Like in India, the workaround is to have a payment-on-delivery option. The document says:

“We face the risk that any of our third-party carriers, who often collect cash-on-delivery payments from our consumers, may become insolvent, in which case our delivery capability would be adversely affected.” You don’t say.

“Even though we would not be able to collect from an insolvent third-party carrier, we would still be obliged to pay our sellers whose goods were already delivered to consumers. The insolvency of any of our third-party carriers could harm our business and financial condition.”

This, it turns out, is a massive problem. The document notes that in Kenya, where about 95% of consumers paid in cash or with cash equivalents on delivery in 2016, “we discovered in early 2018 that €720,000 of cash payments remained uncollected in 2016, the large majority of which was never subsequently collected”.

The problem was that there was an “insufficient cash reconciliation system”. There is now an automated system that allows the company to monitor transactions on a daily basis.

“Even though we have taken measures to reduce the risks of fraud and uncollected receivables, these risks — whether facilitated by our employees, sellers, partners or consumers — remain, due largely to the prevalence of cash on delivery in many of our markets”.

They also note a huge array of problems every African business person will recognise: exchange rate fluctuations, exchange controls, security breaches, arbitrary changes in tax and regulation, fraud, theft. You name it, it’s there.

There are other oddities about the company. One is MTN’s decision to cash out part or all of its stake. MTN is a big shareholder in the group, and the official line is that the company will sell down most of its stake, and use the proceeds to pay down debt. The only thing is that its debt isn’t that large for a company its size: it’s about R68bn. The $600m it’s hoping to garner from the listing will wipe a big chunk of that out. It’s a piece of much-needed good news for the group which has been swamped in disputes with regulators, particularly in Nigeria.

There is also a bit a dispute about whether it is an African company at all, except in the sense of where it operates. It was set up by two French entrepreneurs, Sacha Poignonnec and Jeremy Hodara in 2012, who are still joint CEOs; it is still registered in Germany; its tech centre is in Portugal and most of the management sit in Dubai. But it does have a bunch of African senior management including Tunde Kehinde, Raphael Kofi Afaedor, and notable Nigerian CEO Juliet Anannah.

Although there are lots of chilling warnings in the F1 document, it also includes a range of positives. These are not only generic, like 6% aggregate GDP growth across the continent; a young, fast-growing and rapidly urbanising population, and so on.

More specifically, the company notes that it is retaining its most active users, and repeat customers are making more and larger purchases.

“For example, repeat consumers in our 2016 cohort placed on average four orders with a total value of €259 in 2016, compared to 5.4 orders with a total value of €437 in 2018”.

That makes sense, as it did in the past with Amazon way back when. Once someone has successfully placed an order, and got their goods, they will tend to do so again. Trust is being built into the system.

You have to wonder if, in 10 years’ time, MTN will regret its decision to opt out now, even with all those warnings. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider