OP-ED

Reforming like an Egyptian – a question of incentives?

The return of the generals in Egypt indicates that, at least for the Egyptian elite, radicalism was not an option. And muddling through was not either, explaining a subsequent set of bold economic reforms. The difference it seems between El-Sisi and (former leader Hosni) Mubarak is that the military now realises that ‘they will live and die by the success or failure of the economy’.

“All the old paintings on the tombs, They do the sand dance don’t you know, If they move too quick (oh whey oh), They’re falling down like a domino,” sang the all-girl Bangles in Walk Like an Egyptian.

And fall like dominoes in the Arab Spring they did.

On 17 December 2010 a poor fruit-seller, Mohamed Bouazizi, from Sidi Bouzid in the centre of Tunisia, set himself alight after a run-in with police over his alleged refusal to pay a bribe. His death two weeks later triggered anger and protests, leading to the toppling of long-time President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, the first leader to go in what seemed then to be a heady Spring.

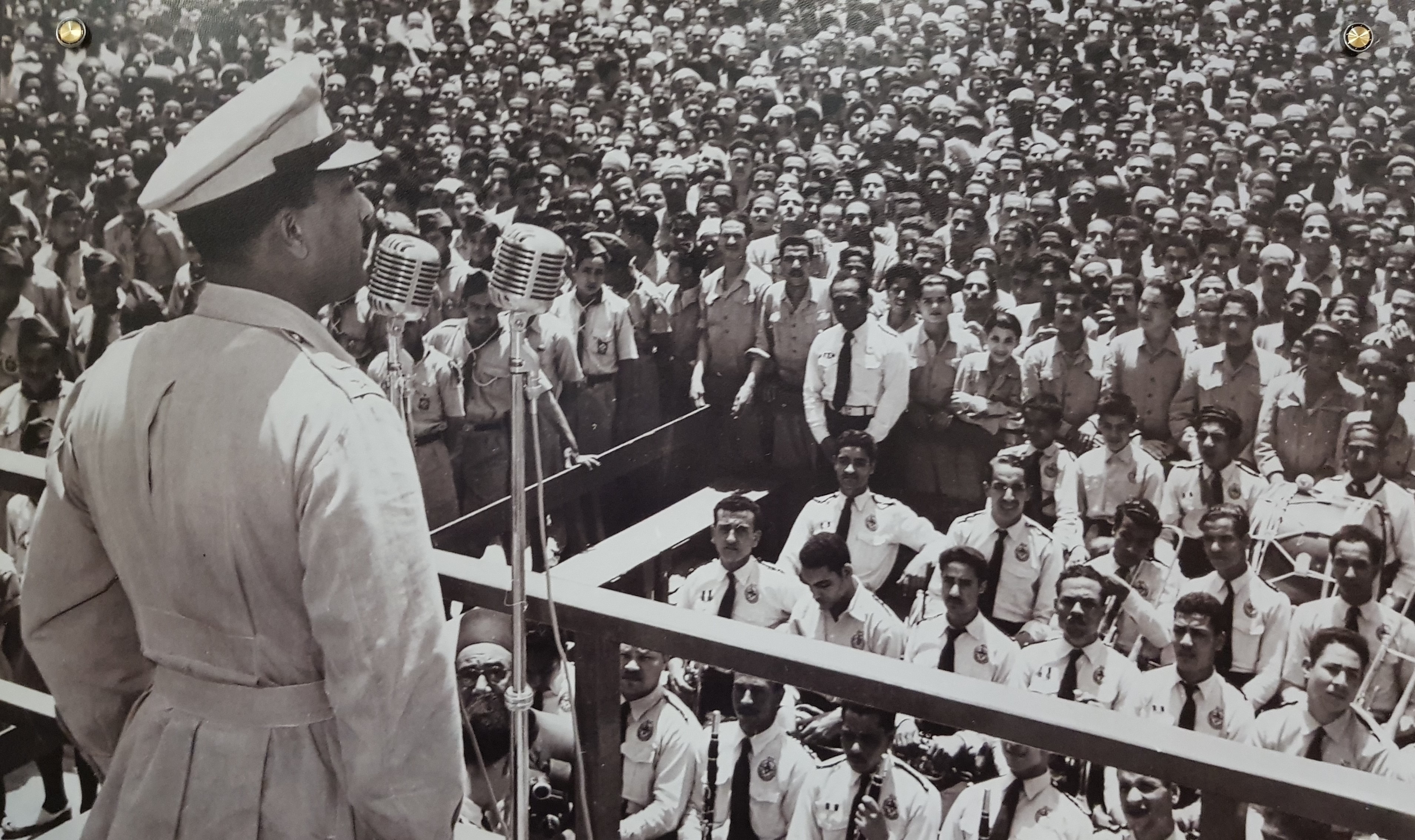

Few incentives to get out of power – El-Sisi and his own brotherhood. Image supplied.

Reminiscent less of the 1968 Prague Spring than the suddenness of collapse of the Soviet bloc of state in Eastern Europe’s 1989 “Autumn of Nations”, Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia on 14 January 2011 in the face of mounting protests. Within the month Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak had resigned as the “25 January” movement occupied Cairo’s Tahrir Square and student protesters fought battles with the army and police. Following a controversial international humanitarian “responsibility to protect” intervention, Muammar Ghaddafi was overthrown in Libya on 23 August 2011, and killed near Sirte on 20 October. In Sana’a in Yemen, President Ali Abdullah Saleh signed a power transfer deal in exchange for immunity from prosecution.

The Arab Spring was approaching its democratic climax. The bloody mess of Syria still lay ahead from its onset in the form of protests sparked in the southern city of Daraa in March 2011 after the arrest and torture of teenagers who had painted anti-government slogans on a school wall.

But the Spring quickly cooled into autumn. Since then the cause of democracy has gone backwards across much of North Africa and the Middle East.

In Libya, the country has effectively divided into two regions, west and east, as it was some 3,000 years ago under the Phoenicians and Greeks in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica.

Back to the future – Egypt’s first four presidents (Naguib, Nasser, Sadat and Mubarak) were all military. Image supplied.

While it has managed to consolidate its democratic gains, Tunisia’s economy has not yet restored the levels of prosperity enjoyed under Ali. Algeria is in the throes of its own transition from a military-backed geritocracy to something that accords better to a population whose average age is just 27.

Yemen remains locked in a bloody civil war, as does Syria. And the regional giant, Egypt, has gone through a cycle of a civilian government following 2012 elections won by the Muslim Brotherhood, the removal as president of its leader Mohamed Morsi by the armed forces a year later, and the installation of the head of the Supreme Court as an interim president before the election of General Abdul Fatah el-Sisi in 2014 with 96% of the vote.

El-Sisi’s rise was a reversion to the practice before 2011 when Egypt’s first four presidents – Muhammad Naguib, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak – all enjoyed professional military backgrounds, given the armed forces’ role in the 1952 revolution which overthrew the monarchy. Some believe that the 2011 Revolution was, indeed, a set-up by the military to remove Mubarak from power and prevent his son, Gamal, from taking over. It was also hardly a clear-cut struggle between autocratic and democratic forces. Morsi was hardly a democrat in waiting. By quickly usurping state powers, he wasted little time in positioning himself as what opposition leader (and Nobel laureate) Mohamed el-Baradei described as “Egypt’s new pharaoh”.

But the return of the generals also indicates that, at least for the Egyptian elite, radicalism was not an option. And muddling through was not either, explaining a subsequent set of bold economic reforms.

The path of Egypt’s civil service, monetary and fiscal restructuring has seen growth spurt to over 5% under El-Sisi. Tied to a $12-billion 2016 IMF deal, the currency has been halved in value, subsidies (especially those on fuel) cut and taxes hiked to reduce a budget deficit which hovers around the 10% mark. Some previous no-go areas are under the knife, including the size of the Byzantine six million-strong civil service and the privatisation of state-owned enterprises, the first 10 (of 228) now being up for sale.

All this is difficult to do in the demographic moment. Egypt’s population has increased from 28 million in 1960 to touch 100 million in less than 60 years, while its sprawling capital has gone from three million to 20 million inhabitants during this time. Like the rest of North Africa, as regional population numbers have surged, youth unemployment has risen steadily.

While espousing Arab nationalism Nasser set the stage for a stultifying statism. Image supplied.

But driving diversification is imperative to creating jobs. Tourism is once more on the rise, bringing in $11-billion in receipts in 2018, nearly double the previous year, though below its $14-billion peak. Other main forms of income remain the Suez Canal ($6-billion) and remittances from Egyptians working abroad ($26-billion).

New infrastructure will help, but as ever it’s the inner stuffings of policy and human capital that will make the difference. Productivity and skills levels will have to change, with expectant social and political pain in the process. For example, Eastern Corporation is Egypt’s largest manufacturing business, producing 85 billion cigarettes annually at its vast factory to Cairo’s east. It’s estimated that the workforce could be cut by as many as 11,000 from the current 14,000 if management was given a free hand. There is little incentive to do so, save higher profits for shareholders, however, as the state still collects its taxes regardless ($4-billion) and it retains a sizeable if underemployed workforce.

The Egyptian pound has halved in value with reforms. Image supplied.

If the small and medium enterprise sector is to take over the driver’s seat of employment from the state, then the latter has to allow it to do so, making permitting easier, and creating the conditions to bring down interest rates from over 20% to enable them to borrow, build and flourish.

The benefits of “authoritarian stability” are a constant reference in this process. While El-Sisi’s policy boldness has rightfully been lauded, it’s a salutary reminder that the extent of the reforms now necessary is precisely a result of the failure to do so during the previous authoritarian government of Hosni Mubarak. It’s also not clear if, for all of the corrective discipline of the IMF, outsiders can much help. After all, aid did little to encourage Mubarak down a reform path either, his regime received an estimated $133-billion in cumulative foreign aid and military assistance. And nor is longevity always helpful. Mubarak was there for three decades, becoming increasingly part of the problem, not the solution.

The difference it seems between El-Sisi and Mubarak is that the military now realises, in the words of a local banker, that “they will live and die by the success or failure of the economy”.

Under Mubarak, admits the Minister of Public Business, Hisham Tawfik, “There was high economic growth which did not filter down, which ignited the Revolution. We must have it filter down to the masses.”

The underlying question is how often does a military (backed) government hand over power in a peaceful way that’s good for the economy and, therefore, the country? And what are the incentives for them to do the right thing?

Tourism is up but fickle and below its peak. Image supplied.

The military is of course unlikely to want to reform itself out of a job entirely, given the depth of its commercial tentacles. It may eventually have no option, not least since democracies have historically performed better in development terms in Africa than their autocratic alternative, not least because of their self-corrective capacity and competitive basis.

Herein lies the paradox. Making democracy work is in the interests of Africa’s people even if it is not always in the immediate interests of African governments and their leaders. DM

Dr Mills heads the Brenthurst Foundation, and is the co-author of ‘Democracy Works: Rewiring Politics to Africa’s Advantage’ (Picador) to be launched in Johannesburg on 27 March.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider