DEATH ON/OFF THE RAILS

The train that killed my brother

This story begins and ends with trains; the train that killed my brother, the train that carries me safely home. It is a story of two countries; of intense beauty and chaos in South Africa versus safety and a more mundane existence in Australia.

“Peter is dead. He’s been hit by a train.” My sister’s voice was monotone, shocked. I took her call in my sunlit home office in the tranquil seaside village of Killcare Heights, north of Sydney.

‘No, no, no, it can’t be. Not Peter.” The news was indigestible.

“I’m sorry. It’s really shocking. Peter is dead.” insisted my sister, a psychologist and retired academic who lives in Stellenbosch. I heard the catch in her voice. She was reeling too.

She explained that when Peter did not return from work by 9pm the previous evening, his wife Morvena Vergnani asked her brother to drive her into Cape Town.

“They went from station to station searching for him.”

After midnight they went to the Cape Town Metro Police Department where a policeman informed them a man had died when he was struck by a train earlier that evening.

Though she had yet to identify his body in the morgue, Morvena told me later that she knew immediately from the policeman’s description of the grey-bearded, “elderly man” in the blue checked shirt that it was Peter.

Police later handed Morvena her husband’s briefcase and phone.

“I don’t remember anything after that,” she sobbed. “I was deurmekaar [confused].”

‘Worst train system in the world’

Peter was a kind, gentle and devout man, who was greatly looking forward to retiring. When he died at Esplanade Station after being hit by a train, sometime around 6pm or 7pm on 7 February, he was literally counting the days until he could finally end his dangerous train commute. There were just 12 working days left before he turned 65 and could retire from the job he loyally worked at for more than 45 years.

There was no word of his death in the newspapers. But in 2017-18, according to the Railway Safety Regulator, 343 people died in South Africa after being struck by trains. What happened to my brother is a microcosm of the tragedy played out in so many families.

Peter did not drive, so had to take trains from his home in Brackenfell to the Supported Employment Enterprises (SEE) factory in Ndabeni where he worked as a pattern cutter in the textile section.

In the last few years, Peter became increasingly anxious about travelling on the overcrowded trains and left ever earlier for work to avoid the worst of the rush hour. In one email to me, he described the Cape Town train system as “the worst in the world”.

With commuters robbed, stabbed and sometimes murdered on trains, he was braced for the risk of crime. As the train carriages were destroyed in arson attacks and the rail system disintegrated, his daily commute became even more frightening.

His workday started at 7.30am and theoretically, his commute should have taken little more than an hour each way. But by October 2016, Peter emailed me that he was getting up at 4.15 every morning to catch the 5.25am train to Bellville. Then he caught a “connecting shuttle” towards the city, got off at Esplanade Station and walked through to Woodstock Station, where he caught another train to work. He was bypassing Cape Town.

“I really have no choice now, because of the trains that were set alight,” he wrote. “A lot of peak hour trains have been cancelled, and the 6 o’clock train I used to take is so full I can’t get in, and people are hanging outside the doors. Besides that, people hang on the front of the train in front of the driver, it’s insane. So I have no choice now to go that route, otherwise, I would arrive late for work every day.”

Scrumming commuters

Peter and Morvena Vergnani. Image supplied.

By that time, around 80 carriages had been burned by unknown arsonists in Cape Town. Living an ocean and continent away in Sydney, I knew about attacks on passengers but was unaware that the trains were being burned in my former home city.

Researching Cape Metrorail trains online, I was appalled at what I found. The reality was brought home by videos of scrumming crowds, ramming their way through the doors and windows of trains at stations. There were bunches of commuters clinging between the canary yellow carriages and leaning out of the open doors of fast-moving trains, while train surfers ducked electric cables on the roofs.

I could not imagine how my skinny brother coped in that crush. It was the polar opposite of the orderly railway system I used in Sydney, where I could board a train alone after dark and feel safe travelling home.

In Sydney, only passengers with valid tickets can get through the turnstiles onto or off the platforms. Uniformed guards check the train doors are clear and shut before each train leaves the station.

I was astonished that the Public Rail Agency of South Africa (PRASA) and its Metrorail division seemed unable to implement similar basic safety measures. In a watershed ruling in 2018 the Constitutional Court ruled that PRASA had a legal duty to protect its passengers against any sort of harm.

More carriages torched

In December 2017, Peter wrote to me: “We have our fair share of delays and cancellations, but thank God, no line closures like the Langa and Khayelitsha lines… To tell the truth, I can’t wait until February 2019 when I retire, then I don’t have to battle with all those train problems anymore.”

By then another 33 carriages had been torched in Cape Town and the rolling stock had been halved. Many train commuters switched to buses or taxis.

In September 2018, Peter forwarded me photographs of seats with ripped-off upholstery in a first-class carriage and said that was why he rode third class most of the time.

“I don’t see why I must pay R340 a month for such shocking conditions…Yesterday there was no upholstery at all, just a metal frame in the entire carriage.’

Then he began catching country trains, when possible, because the seats were better and the coaches less crowded.

That year, 56 more carriages were destroyed, bringing the total to 174 carriages burnt out in three years.

On 2 December 2018, Peter sent a WhatsApp message that he had just 47 more working days left, “then it’s over for good. I look forward to it, especially not waking up so early and struggling with trains that constantly run late.”

Stress leave for the train driver

I flew to Cape Town to attend Peter’s funeral and to find out more about the circumstances around his death. What put him in the path of that train? Was he assaulted? Was he pushed? Did he accidentally fall?

Everyone who knew Peter said he was super careful and would never have walked across the railway lines. It was definitely not suicide.

The detective sergeant handling the initial investigation told me in a telephone conversation there were no CCTV cameras at Esplanade station. The police did not know of any witnesses apart from the train driver. The sergeant said he had been unable to interview the driver because, in terms of PRASA policy, the driver had immediately been suspended on six months of stress leave.

The sergeant noted he had asked the driver for a statement, but he had not been given one so far.

“He asked me to give him a week… I’m just hoping he can bring some light on the whole situation.”

“Can’t you tell the driver that it’s urgent?” I explained the family was worried Peter might have been the victim of a crime.

The sergeant responded: “We are worried about that too.”

However, he explained he could not insist the driver make a statement as he might respond that he was still on stress leave. It seems the driver had a right not to speak.

The sergeant said they were hoping to put out a media release asking for any other eyewitnesses to come forward. By now a week had elapsed since my brother died.

When I called PRASA to find out if they had more information about my brother’s death, a representative offered to put me through to the complaints department. I said I was not making a complaint, I was phoning to find out more information about my brother’s death. She transferred my call to the claims department, where a man told me that once the investigation by the railway authorities and the police was complete, the family could lodge a claim, if negligence was proven.

It seemed a Catch 22 situation. His widow had six months to notify PRASA of an intention to make a claim. But this coincided with the period that PRASA put train drivers involved in fatal incidents on compulsory suspension for stress.

Funeral for a joyous man

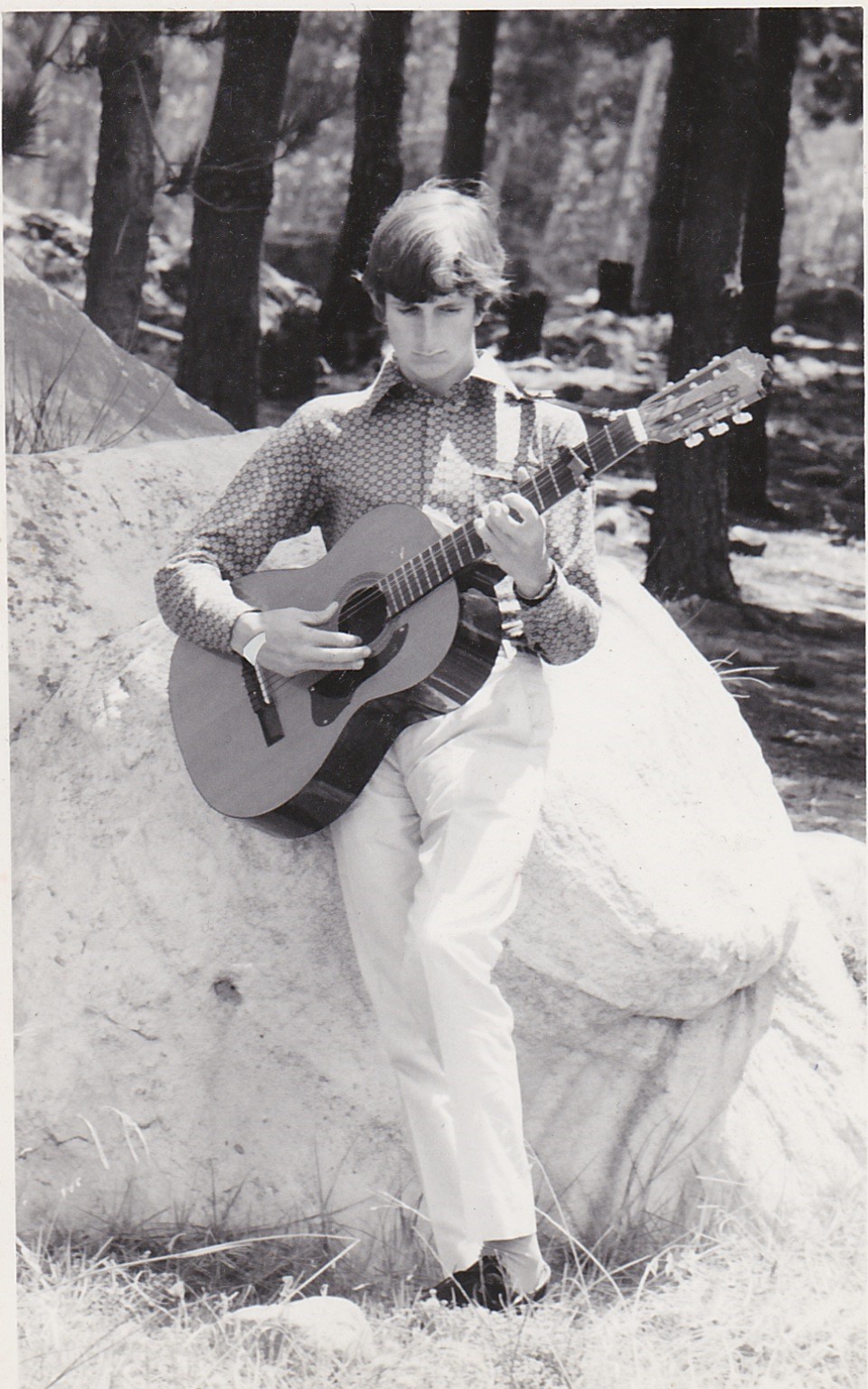

The young Peter Vergnani.

On Saturday, nine days after his death, I gave a eulogy at Peter’s funeral at the Rhema Cape Town North Church. The funeral was attended by about 180 people, a true rainbow nation gathering of people of all colours, whose lives were touched by Peter.

The genial Morvena, his soul mate and wife of 15 years, sobbed in the front pew. She was comforted by her son Ashley, 22, a fine young man who regarded Peter as an inspirational “dad”.

Peter was a joyously devout Christian and a keen guitar player. A trio of his musician friends played evocative classical guitar music in his memory.

Among them was Charles Gowie, a newly retired primary school music teacher, who played regular gigs with Peter in a restaurant, He was devastated to hear about his loyal friend’s death. Later he wrote: “In all he did he was meticulous and careful.”

He speculated Peter might have slipped and fallen as he tried to board the train, possibly shoved by commuters trying to get a place on the train.

“The alternative is just as horrific: that he might have been pushed from the moving train by a jostling, jam-packed crowd.”

Charles wrote: “Nothing is certain: one can only hope that a witness would be forthcoming to tell the true story.”

An incisive mind

Image supplied.

Despite facing challenges that resulted from an undiagnosed lack of thyroid in the early months of his life, Peter had an incisive mind. He endeared himself to people with his frankness and wry sense of humour.

My brother focused intensely on subjects that interested him. He had a phenomenal memory and instantly recalled the exact birth, anniversary and later death dates of all our family members.

Recently he learned the book of Jeremiah off by heart, because a church friend challenged him to do it. He began memorising a second book of the Bible, “not for recitation but for meditation”.

For decades, while he was a bachelor, our lives intersected only tangentially – usually at family meals or celebrations. In South Africa, I was a journalist and foreign correspondent, bringing up two lively daughters with my husband, while Peter was wrapped up in his work, church activities and music.

In 2001 I moved to Australia and returned to Cape Town all too rarely. Two years later, I flew over to attend Peter’s wedding to the warm, sociable Morvena. They had met shortly before and had a whirlwind romance. He adored her and became a proud stepfather to Ashley, then eight. They moved to Brackenfell to be closer to her large, extended family and Ashley’s school.

Then in the last few years Peter discovered social media and began a lively conversation with me through emails, Facebook and WhatsApp messages. Sometimes he wrote daily. I was amazed at how articulate he was.

He wrote about the great plans he had for his retirement. Peter had excitedly compiled two books of “early 15th century lute transcriptions for guitar” that he intended learning. His checklist included improving his Portuguese; learning conversational Xhosa and Zulu, and volunteering in the library several days a week.

Searching for eyewitnesses

After Peter’s funeral, I tried to find out what happened in his last hours. When the very helpful human resources manager, Priscilla Rustin, at Supported Employment Enterprises Ndabeni said that there might be an eye witness I could speak to, I drove immediately to the factory. It was an airy building, rather than the gloomy place of my imagination.

Priscilla, who described Peter as a “very meticulous worker”, called several of his colleagues to speak to me. Kaylene Brink, who worked in the kitchen, said she and Peter caught the train together on the afternoon of his death. The train stopped unexpectedly outside Woodstock station at around five o’clock for half an hour. Many passengers climbed down and walked along the tracks to the station. Kaylene noted: “Peter said he would not jump out. It was dangerous to jump out…”

When the train finally reached Woodstock Station, Peter said he was in a hurry and rushed off to catch the 5.35pm train from Esplanade station, just two minutes walk away.

The possible eyewitnesses turned out to be a married couple, who also saw Peter alight on the Woodstock platform. That was the last they saw of him. They all said Peter used the pedestrian bridges and would never risk crossing the railway lines.

Priscilla took me down to the factory floor, so I could see the cutting table where Peter worked. Light streamed through the skylights onto groups of people at sewing machines and high piles of hundreds of hospital print sheets and garments.

I chatted to his work team and leader. Peter had trained up a young man, Luthando Hlahleni, to replace him. Luthando said: “Peter was happy on that day. We were making jokes, talking and singing.”

They were distressed at his death. But I was relieved when the HR manager said: “He loved what he did.”

As I left, an employee beckoned me aside and showed me two messages on a Facebook Metrorail Commuters group. One message at 3.22am on 8 February said: “There’s talk about someone falling out of a train before Esplanade station. Anybody have any information on this?”. Another person responded, “3581 the Wellington Business Express was involved in a passenger related incident and is delayed”.

I managed to get through to the sergeant investigating the case again. He said the post-mortem results showed Peter’s injuries were consistent with his being run over by a train. The upper part of his body showed no evidence of assault. The sergeant had not yet got a statement from the train driver.

I still had no answer as to how my brother landed on the tracks.

A safer Sydney commute

I flew back to Sydney, jetlagged after a 23-hour series of flights. The final leg of my journey home involved taking two trains. On the underground city route two spindly silver-haired women, probably in their eighties, sat relaxed in an almost empty carriage.

I wheeled my luggage through Central Station and swapped to a country train, which glided towards my local station. When a ticket inspector came around, I told him about my brother’s death. I said I had a peculiar question to ask: “Can the passengers on this train push open the carriage doors while the train is travelling?”

The inspector looked astonished: “You’re quite safe on this train,” he said. “Nobody can open the doors while the train is moving, they lock automatically.”

He thought I was worried about my own safety.

But I was remembering Peter’s words:

“You are so blessed to have such an amazing transport system in Sydney. If we didn’t have all the financial commitments and family commitments, we would also emigrate to Sydney.”

It was the growing crime rate in Cape Town that made my husband accept an offer of a transfer and promotion to Australia in 2001. We were worried about future safety for ourselves and our daughters, but thought we might return.

It’s a move I find troubling: how do you weigh up insecurity in a country you love versus exile in a land 10,000kms away? In Australia, I hardly worry about crime and can safely commute on public transport into my old age… But I miss the excitement, vibrancy and heart-stopping beauty of Cape Town.

Since returning to Australia, I have made dozens of attempts to phone the Woodstock police. Multiple calls clicked off after a few rings. Twice I got through and was asked to call back after 3pm, which is 11pm Sydney time.

When I finally got hold of the sergeant again, he told me Peter’s docket has been handed to another detective for investigation. He confirmed a press release has been issued and suggested that the other sergeant could give further details.

Peter’s abridged death certificate states that he died of “unnatural causes”, and the Forensic Pathology Services case file certificate states that his category of death was as a result of a train casualty.

Now, one month since Peter died, I have not yet managed to get hold of the new investigating sergeant. But as I wrote this, I found Morvena’s brother has made contact with the detective who has agreed to give him regular progress updates. I am hoping we will finally get answers about what happened in those last minutes before my brother landed under a train.

It is too late to save Peter. But other commuters across South Africa deserve a far safer, more reliable, 21st-century train system. No one should have to literally risk their life commuting to work. DM

Copyright Linda Vergnani.

Linda Vergnani is an award-winning freelance journalist. She is a former South African correspondent of The Chronicle of Higher Education. See more at www.lindavergnani.com

Become an Insider

Become an Insider