THE PROMISED LAND

How expropriation could work … without destroying the economy

The land “debate” wreaked havoc with the SA economy last year. But the fact is, addressing what Cyril Ramaphosa calls SA’s “original sin” was necessary, and the arguments against it ignore the depth of emotion about land. But the trick is to do expropriation without compensation in a way that will boost the economy and enhance social stability – not destroy it.

A year ago, those who were optimistic about SA’s chances of stronger economic growth for 2018 had every reason to feel buoyant.

Cyril Ramaphosa had just won the ANC presidency at the party’s Nasrec conference by the slightest of margins; Jacob Zuma’s departure as president seemed inevitable; governance seemed likely to improve from there; and it was just a matter of time before the money rolled in. Instead, the economy stuttered, and grew by less than 1% in 2018.

One of the main problems, of course, was that same Nasrec conference, which resolved that: “Expropriation of land without compensation (EWC) should be among the key mechanisms available to government to give effect to land reform and redistribution.”

Econometrix economist Azar Jammine says that “without a doubt” this was the most important reason economic growth failed to deliver a “Ramaphoria dividend”. Just look at when economists began downgrading SA’s growth forecasts, says Jammine: right after parliament voted for the first time in February last year to allow EWC.

It was a motion first proposed by the EFF (Julius Malema’s party wanted land to be nationalised), then amended by the ANC. The ANC ’s motion that was finally passed said people would be allowed to own the land that was expropriated.

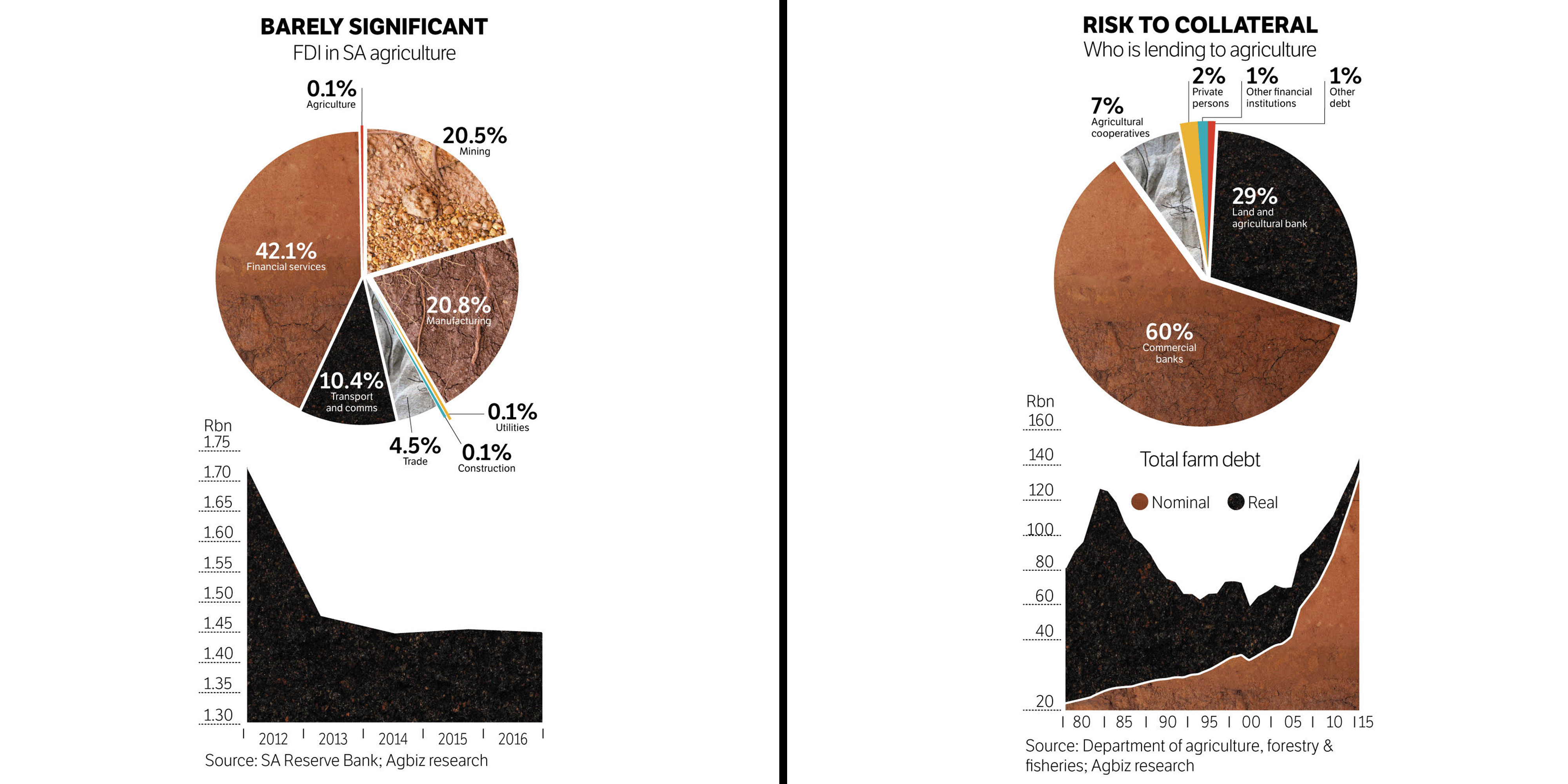

Jammine says there’s clear evidence that the land debate caused a decline in the ratio of capital investment to GDP. “In the third quarter [of 2018] it fell to 17.7%. That’s the lowest ratio … since before the build-up to the 2010 Fifa World Cup.”

In other words, the ANC’s land decision at Nasrec “in one fell swoop destroyed whatever hope there was of a surge in capital investment that might resurrect sustainable economic growth”, he says.

Correcting an original sin

For SA as a nation, forged during the colonial era and then moulded by apartheid, land is, as Ramaphosa has said, the “original sin”.

As advocate Tembeka Ngcukaitobi details in his book, The Land is Ours: Black Lawyers and the Birth of Constitutionalism in SA, land was taken by force from black people for white people to farm and to live on. This dispossession, and the concomitant forced migration of blacks into towns andcities to work for whites, are the major causes of racialised inequality today. It’s indisputable that black wealth was taken by white people.

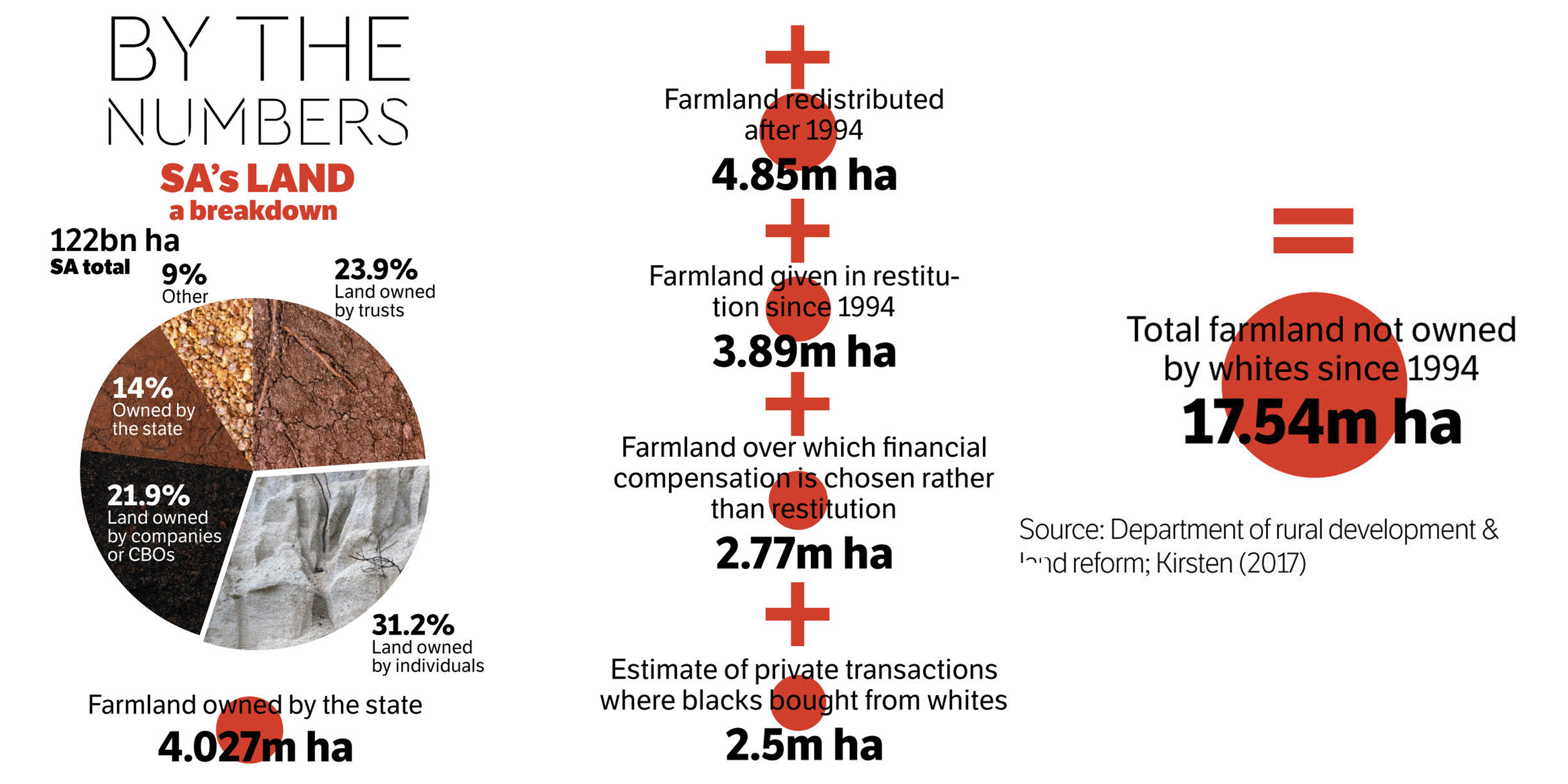

The government’s land audit report in November 2017 said SA had a total of 114.2-million hectares registered at the deeds office. Of this, the government owned 17.1-million hectares, while trusts owned another 29.3-million and companies owned 23.1-million.

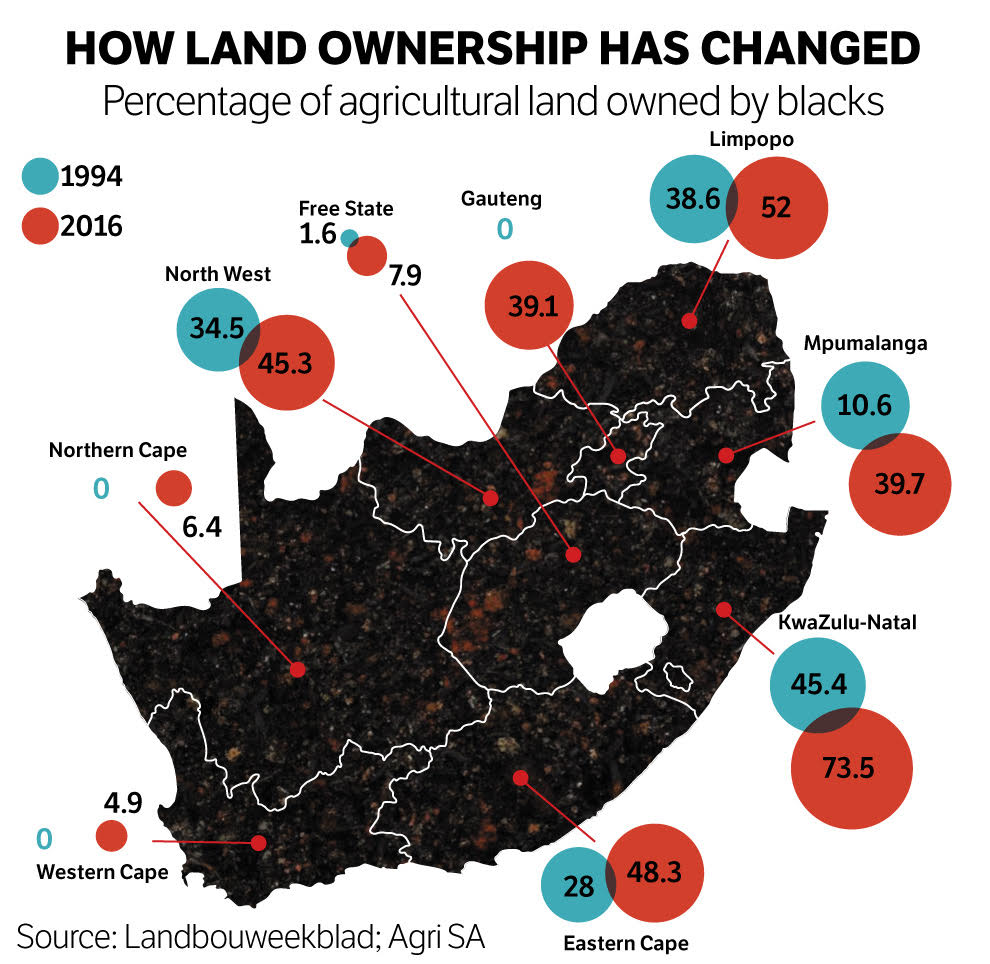

Of agricultural land in individual ownership, whites owned around 26.6-million hectares, blacks around 1.3-million hectares, coloureds 5.2-million hectares and Indians 2-million hectares .

All of which means that land restitution and E WC have an inherently powerful political dynamic.

It is interesting, however, that it has only been since the emergence of Malema as a political force (first through the ANC Youth League and then as leader of the EFF) that land has become a big political issue. In some ways, it’s still not the priority it should be: the ANC government budgeted more money for VIP protection last year than it did for land restitution.

The politics of land is intensely complicated. Some say that it’s simple: the will of the majority, who support EWC, should hold sway. But even that’s not so cut and dried – given what would happen after expropriation, and how that land would be distributed.

In its election manifesto released a few weeks ago, the ANC did not promise any kind of “land grab”. Instead of reinforcing the fears of those who believe land would be the most powerful election promise, the ANC manifesto played it incredibly safe.

Its election pamphlet says: “We will support the amendment of section 25 of the constitution to clearly define the conditions under which expropriation of land without compensation can take place. This should be done in a way that promotes economic development, agricultural production and food security.”

In other words, no land grab.

Ronald Lamola, the Ramaphosa confidant and ANC national executive committee (NEC) member who is leading the party’s processes on the land issue, is very clear that the ANC will not use it to win votes.

“We are not doing that,” he said in an interview with the FM. “The past 25 years have given us experience. If we speak about using land as an election tool, the PAC would have been the government of SA since 1994.

“The ANC believes the land issue must be handled properly and with care, and must not damage the economy.”

So far, the party has tried to do that. Towards the end of 2018, the Expropriation Bill was gazetted – the clearest articulation yet of just how EWC will work.

Encouragingly, it did not speak anywhere of nationalisation, and said expropriation applied only to land – not intellectual property or anything else. And it laid out the five types of land that may be subject to EWC: land occupied or used by a labour tenant; land held for purely speculative purposes; land owned by a state owned entity; land abandoned by its owner; and land that is worth less than any state subsidies it might attract.

Lamola’s reassurances that the ANC has no plans to destroy the economy also resonates with the Nasrec resolution on land. Intriguingly, that resolution was only released in March last year – three months after the ANC conference ended. This may lead some to suspect there has been “political management” of the issue.

That resolution makes clear that in implementing expropriation: “We must ensure that we do not undermine future investment in the economy, or damage agricultural production or food security. Furthermore, our interventions must not cause harm to other sectors of the economy.”

But look deeper into the wording and it appears there was huge contestation on this issue. The context of December 2017 was that, generally speaking, those supporting Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma’s bid for the ANC presidency backed EWC, while those supporting Ramaphosa opposed it. The resolution seems a compromise.

It also seems clear that Ramaphosa himself did not want this resolution to be passed, but has now had to manage it all politically. Considering SA’s past, this isn’t easy. Just look at the intensely emotional testimony at parliament’s public hearings last year on whether section 25 of the constitution should be changed.

People explained, in some cases, how they and their parents and grandparents had been forcibly removed from land that had been the source of their wealth. There were many cases like that of Shadrack Ndlovu, who testified: “My father and my brother worked on a farm and we received R3 salary …. they just removed us and we lost our livestock.”

There were many similar stories, which spoke of a real desire for land. This accords with a study in 2006 by the Institute for Poverty, Land & Agrarian Studies (Plaas), which found that one-third of black South Africans want access to land for food production and another 12% want land for a variety of other reasons.

It’s also a racial identity issue, because it is black people who lost land, and white people who gained it. In other words, were this to become a defining issue of the election, it could see parties tempted to pit different race groups against each other.

Should that happen, the DA, which has been battling with issues around its own identity, could find a clear purpose: it would be able to campaign as the party wanting to retain the constitution in its current form, and it would act as a scaremonger among the middle classes saying that the ANC was going to take all their assets.

While that would certainly not propel the DA to victory in the elections, it could help it to fare better than it might otherwise. Certainly, it could ensure that middle-class minority voters turn out for them. At the same time, the ANC’s reticence to make any stronger statements on the land issue may be a reflection of its own internal dynamics. Any change to section 25 would require perhaps between 20 and 40 words to form the new clause.

Considering how power actually works, it seems almost certain that the ANC’s NEC would have to sign off on those words and phrases. And it is difficult to see how an NEC as divided as this one, containing contrasting characters like Tony Yengeni and finance minister Tito Mboweni, could agree on the new clause. All the interest groups within the party are aware of how this issue could divide the ANC during an election campaign.

Broken land reform promises

Of course, a crucial reason that the land issue now has such power is that the current system of restitution, in which landowners receive market-based compensation, has been an absolute disaster.

Lamola says that after 25 years in government, “We can see that we cannot run a market-related land reform programme; it won’t work. It must be done as the constitution says – through a just and equitable basis. It’s an evolution of the ANC policy learning from (our) experience.”

But like many of SA’s problems, that may be a failure of implementation, rather than a case of not having the right laws and rules. The cold facts speak to a gridlock. Since 1994, the government has only redistributed 4.8 million hectares of land to claimants – less that 4% of all SA’s land.

Part of the problem, of course, has been money. Experts estimate that to return 20% of agricultural land to black South Africans, as the government wants, would take R5-billion. Yet the actual allocation over the next three years is just R4-billion.

For lawyers, who have been studying this issue for some time, a big part of the problem is the way the current land claim system is being administered.

Elmien du Plessis, an associate professor of law at North-West University, says: “If you institute a restitution claim, there are so many administrative steps to go through, it becomes almost impossible from the start.”

The many legal steps in each claim could be a huge stumbling block. At each of these steps, a legally binding decision has to be made. Which means each step is then liable to review by a judge, and thus the process can be tied up in court for years.

Considering the emotions involved, it is entirely likely that organisations opposed to the process would challenge every single step of any case. This has the potential to drag the courts into politically contentious disputes – delaying reform for longer.

Du Plessis says the problem is “an inert state with administratively heavy legislation, which is a recipe for disaster”. Unfortunately, she says: “The new Expropriation Act is just as heavy, with just as many steps.”

However, one aspect of the law rarely spelt out is that it is entirely possible for land to be expropriated, and compensation to only be paid later. Du Plessis says the amount of compensation can be “determined and paid after the expropriation” in certain circumstances. So, it would be possible for farmers to have their land expropriated, and then, after a determination process that could involve legal challenges, learn what they would get in compensation.

At the same time, decisions around the value of the land being expropriated can also be heavily contested. The Office of the Valuer-General is supposed to determine the value in cases of land reform. But some doubts have been raised about those calculations.

Then there’s a deeper philosophical issue about whether real restitution can happen. Previously, you were allowed to lodge a land claim if your land was taken after the 1913 Native Land Act was passed. But history shows us that by 1913, most black people had already been dispossessed of their land by the colonial authorities.

Du Plessis says this means that any restitution would be limited anyway. “You would spend so much money and only benefit a few people. What then is the aim that we are trying to meet?”

The problem, of course, is that for Du Plessis (and many others), “restitution has a restorative justice element – someone who got kicked off land gets his land back”.

But, she asks: “Should we shift our focus to redistribution, should the focus be more on how we give more people access to land in a way that makes sense and is not so administratively heavy?”

While much of the nation is fixated on whether expropriation should happen, there is precious little discussion about what would happen afterwards. It seems likely there would be huge arguments about how that land would be distributed –with competing claims to it.

Take the hypothetical example of a piece of land in Mpumalanga now in the hands of a white farming family who bought it at below market rates after a group of black families were forced off the land during apartheid. Let’s say the descendants of that black family have done well and joined the middle class.

Meanwhile, another group of people who have nothing stay in shacks next to the property and subsist on social grants. This group might be frustrated to see middle–class people receiving that land. On the other hand, if that middle-class black family were denied its right to the land – this time by a black government – it might also feel huge frustration.

The potential for conflict can hardly be overstated. So land reform will be no small task to manage for the ANC, as the presumed victor in May’s elections.

Lamola says the party is planning a new system that may focus on redistribution but include elements of restitution. “People would still be able to claim … but there is also a process of redistribution.”

He says there will be a means test, so “those who need the land” will benefit. Not all South Africans will be able to claim through the restitution process, Lamola says, but those who need land – “the youth, women, vulnerable groups” – will be given land too, even if they cannot pay for it. This would be managed using similar criteria to those applied when allocating RDP houses.

There have, of course, been problem s with RDP housing lists – people not getting them for years, or their place on a list being “sold”.

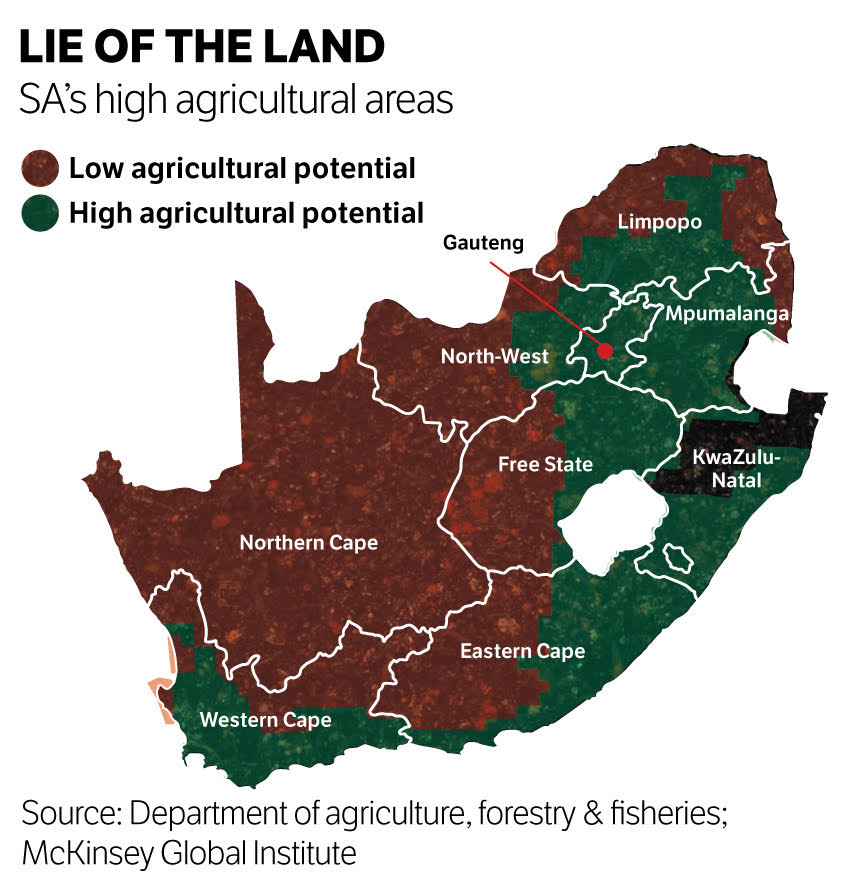

Still, these lists have been generally accepted, and have the advantage of already being in existence. There will still be difficulties: some portions of land will be inherently more valuable because of their location. As the map (below) shows, much of SA isn’t of high commercial value, for one thing.

But the ANC also wants to use this moment to create new black farmers – commercial or subsistence – and help those who are already farming but need more land.

The nationalisation red herring

So how will the land actually be owned?

This is one of the most important aspects and brings to the fore the tension between those who want land to be nationalised and those who want individual ownership. The EFF in particular believes land is too important to be owned by individuals, and should be controlled by the state. “This thing of title deeds is a set-up,” said Malema in parliament in August 2018.

Just after New Year’s Day, former president Jacob Zuma released a video on his new Twitter feed, agreeing with the EFF. “European countries don’t sell land to private people or companies. It is in the hands of the state. If you want to use it, you lease it. Why in our case should it be different ?” he said.

Only, this isn’t the case in Europe, which generally supports freehold individual land ownership. Zuma’s view that “no land is sold to individuals” in Europe is entirely incorrect.

But another problem with nationalising land is that state officials would then have the power to allocate it – creating fresh opportunities for gatekeeping and corruption. The ANC, by and large, seems resolute that nationalising land would be the wrong path. Ramaphosa said in parliament: “We should not rob our people from this deep yearning and quest to own their own property.”

The ANC’s manifesto proudly states land should be owned in various forms, including individual tenure, communal ownership and state-owned land.

This smacks of the typical ANC approach of trying to appease all parts of society, but it may also reflect the party’s internal dynamics. Many of its leaders are themselves middle class and own property. Former cabinet minister Valli Moosa, who played a key role in negotiating the constitution, has said publicly that the ANC wanted the current land clause in the constitution to ensure that black people could not be dispossessed of their land again. So there is a strong feeling in the ANC that people should be able to own land privately.

One of the hot-button issues of the expropriation debate is the situation in areas administered by traditional leaders. They hold significant political power, and are unlikely to take kindly to having their powers of administration over this land curbed in any way.

Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini, for example, controls the land held by the Ingonyama Trust – a unique situation created by the apartheid parliament days before the 1994 polls. In July 2018 he made threatening noises, saying he, like his forefathers had, would fight any attempt to “take” the land.

“I will be victorious against those who are trying to take my land,” he said.

Ramaphosa then rushed to Zwelithini to reassure him that the land he controls would not be affected by expropriation, showing how much clout the king wields in KwaZulu-Natal, where the ANC has some unity problems.

Yet Lamola says the ANC also wants to upgrade “security of tenure” for people living on communal land.

This could lead to traditional leaders losing some of their powers, which may have political implications. Some in the Congress of Traditional Leaders of SA have already said they should withdraw their support for the ANC, so any new tussle over land could spill over.

How expropriation could boost the economy

Critically, it is not a fait accompli that EWC has to be negative for the economy. Jammine says that done right, it could actually “overnight transform this economy, and government could achieve its social and political goals without having to damage what is already working”.

Jammine cites Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto, who says granting title deeds to masses of people “has simply transformed various economies around the world”. This is because they are able to use that title “to realise and generate cash and start-up businesses”.

This could kick-start what Jammine calls the “gearing phenomenon, where land is one of the keys to building wealth. You can buy a house, mortgage it and rent it out.” He says this has vast wealth-creation potential for millions of people who under the current system cannot generate finance from the land on which they live.

Jammine’s words will comfort those who see the land debate as entirely negative. And while it is true that giving titles to people could transform our economy for the better, for that to happen, difficult choices and political trade-offs will have to be made.

It is also not clear it would be a magic bullet. Some development economists suggest the poor would not be able to exploit the value of that land, while themiddle classes and wealthy would. They argue that such a policy could, in fact, increase inequality.

But in Peru, De Soto’s ideas appear to have worked, helping the economy to grow on a sustained basis for 18 years at one stage. However, a key element in Peru’s success was the will of the state. It ensured it was able to manage a land tenure system through a process of registration. But in SA, questions will be asked about the government’s capacity to emulate Peru; particularly after the revelations about the Special Investigating

Unit probe into land reform.

Meanwhile, there is the potential for the political noise to be amplified in a way that could damage the economy further. Still, at least the ANC has made it clear it is determined to contain any damage, while trying to ensure a positive outcome.

The result of the land debate may well hinge on whether the party has the power, and will, to achieve that. DM

This article was also published on Thursday by Financial Mail.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider