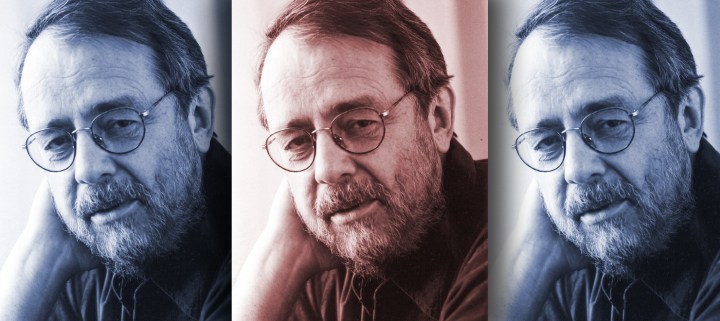

Hugh Lewin (1939-2019)

Anti-apartheid fighter, author and TRC official Hugh Lewin — a man who never gave up

Hugh Lewin, who died at home in Killarney, Johannesburg on Wednesday, 16 January, at the age of 79, left behind an intricate chronicle of his experiences as a South African freedom fighter.

In two memoirs, essays and poetry Hugh Lewin detailed his battle with the dictates of his Christian conscience, grappling with the complexity of commitment, betrayal, forgiveness and self-understanding.

In 1964, Lewin spent seven years in incarceration for sabotage. His father, William Lewin, an Anglican parish priest who died in 1963, had in his last words to Lewin stressed the need for honesty at all times.

Then a member of the African Resistance Movement (ARM), a small, obscure clandestine group using sabotage to overturn the state, Lewin, 24 years old, clung to these words. He was determined to honour his commitment to a just South Africa, willing to face the consequences of his actions, he said.

He later put his revolutionary zeal down to “youthful bravado”.

In Lewin’s speech from the dock at his 1963 trial, he attributed his decision to commit sabotage to his beliefs: That all men were equal in God’s eyes and that whites needed to be shocked out of their complicity with the state. He described the ARM as “disorganised”, their activities as “sporadic”.

Adrian Leftwich, the student leader who recruited Lewin to ARM, became Lewin’s best friend before turning state witness, an event that led to the incarceration of Lewin and six other comrades.

Lewin has detailed his prison experience in the classic prison memoir Bandiet; Seven Years in a South African Prison (1974). The book was banned, republished in 1982 and again in 2002 as Bandiet Out of Jail, with additional material, including essays and poetry, for which he was awarded the 2003 Olive Schreiner Award for prose.

In 2012 he won the Sunday Times Alan Paton Award for non-fiction, for Stones against the Mirror: Friendship in the time of the South African Struggle.

Hugh Lewin was born in Lydenberg in the Eastern Transvaal, (now Mpumalanga), on December 3, 1939. The story of his family life is saturated with a sense of distance. He described the acutely depressive episodes that removed his missionary nurse mother, Muriel Lewin, from the family, even when she was present and his father, whose love and compassion he absorbed, who was 58 when Lewin was born. He was confounded by Muriel Lewin having kept secret the fact that her grandmother had been Jewish.

The family moved to Irene, Pretoria, when Lewin was a year old; at eight he was sent to St John’s College, a private Anglican boarding school in Johannesburg. He considered the college a good training ground for prison, “an alien world, a Christian aristocracy dominated by privilege and all the prejudices that went with it”.

In his final year at school, as the guest of the British Anglican priest Father Trevor Huddleston and the other fathers at the Community of the Resurrection in Sophiatown, Johannesburg, Lewin first confronted the reality of apartheid’s ravages and structural violence.

This influence was among the reasons he wanted to take the cloth after earning a Bachelor of Arts degree at Rhodes University in Grahamstown in 1960. However, he felt unready for the rigours of the priesthood and instead taught for a year in Pietermaritzburg in KwaZulu-Natal and began working as a sub-editor at Drum Magazine and Golden City Post.

In an interview about Bandiet Out of Jail, in 2002 Lewin discussed an essay that had been recently published by Leftwich, “I Gave the Names” in Granta 78. Leftwich confessed his culpability, took responsibility for his actions, which he also attributed to the fear before the prospect of hanging in detention. Lewin dismissed what he called Leftwich’s “dishonesty in trying to justify his position… I have nothing to say to him”, he told me.

However, Lewin had already confessed in Bandiet that he himself had given a name. Under pressure of torture, Lewin revealed the name of John Harris, an ARM member he had himself recruited into his sabotage group in 1963 and who was hanged for detonating a bomb in the Johannesburg train station in 1964.

The fact that the security police already had Harris’s name, given by another of Lewin’s recruits, John Lloyd, made no difference, he said. Lewin felt responsible for the bombing that had taken the life of a 77-year-old grandmother and seriously injured two others. This was because before Lewin was imprisoned he had given Harris the information he needed to carry out his deed.

It was only in 2012 that Lewin was able to cut the Gordian knot, disentangling his own guilt from his rage at Leftwich in Stones against the Mirror. His own fear remained, astonishingly, with him as late as June 1997 when Lewin was serving on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Human Rights Violations committee. Lewin was attending the amnesty hearings for the assassination of communist leader Chris Hani by Janusz Walus and Clive Derby-Lewis.

There he met his former torturer, Johannes Victor, a lieutenant in the security police who was by then a retired brigadier-general. “Thirty-four years down the line — in a newly democratic South Africa, where men like him no longer had any power — still I sat sweating in the audience as Victor leaned forward on the stage…” In Stones, Lewin describes a face-to-face meeting with Victor, where he shook his hand firmly, “I’d broken out of his web of fear”.

In Stones Lewin described the build-up to his meeting with Leftwich, whom he visited in Leeds, some 40 years after the name-giving. He felt the lightness of release, the warmth of regaining what he had lost as he succeeded in shattering his own mythologies, he wrote. Unusually in our present time, for Lewin, friendship assumed almost unfathomable depths.

Lewin included a new essay in Bandiet Out of Jail — describing the state’s confiscation of the ashes of Bram Fischer, the Afrikaans lawyer and anti-apartheid activist who defended Nelson Mandela and others at the Rivonia Trial (1963-1964), where they were convicted of sabotage and sentenced to life. The essay elaborates on the Truth Commission submission of Fischer’s daughters, Ruth and Ilse.

Lewin’s own life had become inextricably linked to Bram Fischer’s before they met in prison, where he witnessed Fischer’s brutal treatment during his illness; first through his attraction to Ruth Fischer at 13; later when Bram and his wife Molly Fischer became comrades, then through his marriage to Pat Davidson, Molly Fischer‘s cousin.

In 2002 Lewin asked Helen Suzman to launch his book. Why?

“Don’t box me!” he said. “My politics haven’t changed, “the healthy dose of socialism I imbibed when I entered the left through the liberal door remains.”

He was referring to his early membership of the Liberal party, whose efforts he found to be “pathetic”. At the launch Lewin recalled Suzman’s friendliness and good cheer, “and though she disagreed with our politics and suffered battering in Parliament — she became our watchdog and protector”.

He was thrilled with Bandiet’s re-publication.

“People say I am obsessed about prison. It’s not true! Once out of there, everything changes, weighty issues of selfishness and behavioural quirks are erased by the impact of colour. When I was kicked out of the Fort (prison) I sat in a gutter and looked at the colours of the streets of Hillbrow… I have done my time, and I am free.”

Lewin’s journey had brought return: Released from prison in 1971, he was forced into exile, spending 10 years in England and a further 10 in Zimbabwe, where he founded the imprint, Baobab books. He had also headed the Institute of Advanced Journalism.

With Fiona Lloyd, his long-time partner, he extended his Truth Commission work, as an adviser to the media in crisis-stricken areas including Sierra Leone. In 2015, the international best-selling Jafta series of children’s books, set in South Africa, written by Lewin and illustrated by Lisa Kopper, was reprinted in South Africa, translated into seven languages and donated to schools across the country.

Hugh Lewin was a quiet, mild-mannered person who took his good time in all of his endeavours; he never gave up. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider