DRC’S MOMENT OF TRUTH

A Heart of Lightness in the Congo, finally?

The DRC has just had its first real national election for a peaceful transfer of presidential authority. However, the Catholic church, and the leaked election data that appears to be the real results, claim that Martin Fayulu was the winner and not Felix Tshisekedi. SADC is pushing its idea of a government of national unity, and South Africa seems to be trying to find a way through it all without picking a winner.

With additional whistle-blower data reporting by Marianne Thamm

During the weekend, the data leaked by a whistle-blower claiming to be a DRC National Independent Electoral Commission (CENI) high-level insider appears to confirm the claim by the Catholic election observers that Martin Fayulu was the true winner. The data claims Fayulu garnered 59.42% of the vote and not 34.7%, as announced in provisional results released by the commission on 10 January. This would indicate potential massive electoral fraud.

The whistle-blower-supplied data, which has not yet been fully independently verified, indicates that Fayulu received 9,325,786 (or 59.42 percent) of some 15 million votes cast, compared with provisional victor, Felix Tshisekedi, of the Union for Democracy and Social Progress’s 2,977,290 votes, which amounts to only 18.9 percent.

Outgoing President Joseph Kabila’s handpicked successor, Emmanuel Ramazani, according to the leaked data based on a 2,060 page-breakdown of votes cast from each and every voting post in DRC, received 2,910,227 or 18.5 percent of the vote.

With a voting population of around 40 million, the 15 million votes cast, as claimed by the whistle-blower, reveal a low turnout for these crucial presidential elections.

* * *

‘The mind of man is capable of anything – because everything is in it, all the past as well as the future.’

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

For half a millennium, the vast territory in the centre of the African continent, now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the DRC, has had both very bad press and even worse events befall it. For several hundred years, from the late 15th century onward, the Kongo kingdom (in south-eastern DRC and northern Angola) became a major slave trading state in association with the Portuguese and Spanish, capturing its victims from surrounding clans and kingdoms and selling them so they could labour endlessly on plantations.

Many years later, as a result of the explorations, popularisations and exploitations by Henry M Stanley (he of “Dr Livingston, I presume” fame) of his travels and then as the agent of King Leopold of Belgium, the bulk of the Congo River basin became the personal possession of Leopold. In this way, Leopold built up a vast fortune from exploiting the region’s potential for the cultivating of rubber trees, harvesting tropical hardwoods and butchering elephant for their tusks — their ivory was perfect for billiard balls and white piano keys, among other household goods.

Leopold’s mastery of the so-called “Congo Free State” was so horrendous, with a death toll numbered in the millions as indigenous inhabitants were forced to deliver specified quotas of raw latex or else (with the “or else” often meaning either the amputation of a hand or death), that eventually, international pressure liberated the territory from the grip of the king, passing that tortured land along to be a colony of Leopold’s country instead.

While Belgium’s colonial rule was less brutal than had been Leopold’s as his personal fiefdom, it was still profitable for its metropole via a flourishing system of minerals exploitation and the construction of infrastructure suited for the export of those profitable minerals.

The southeastern province, in particular, Katanga, yielded prodigious amounts of copper, cobalt and uranium, among other prized ores.

(Little known fact: The DRC’s uranium ore was a key part of the Allied war effort in World War II. It was processed in Johannesburg before being sent to its ultimate consumer – the Manhattan Project.)

But, as the decolonisation of the African continent built up steam, by the time the Belgians suddenly upped stakes, they left a nation with virtually no local medical doctors and scarcely more university-trained civil servants for senior administrative positions.

Patrice Lumumba, the country’s first prime minister, was assassinated (reportedly with the connivance of western nations) and eventually, Joseph Mobutu (later relabelled as Mobutu Sese Seko) emerged as the country’s president after more chaos.

In the meantime, Moise Tshombe had led a rebellion of the breakaway province of Katanga (with its mineral wealth) — in association with the European-based mining houses operating there. Along the way, UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld died in a suspicious plane crash in 1961 just over the border in what is now Zambia, while en route to broker a peace deal for the Congo.

Under Mobutu’s three decades of rule, the country’s economy and political system both decayed, while the levels of corruption reached astonishing levels. Mobutu’s renamed nation of Zaire became a must-visit for journalists and disaster-essayists to catalogue the ultimate horrors of the big-man, post-colonial rule in a fast-failing African nation. (Of course, the writer Joseph Conrad had been there first, with his cautionary tale of barbaric primitivism and depravity after Mr Kurtz went up-river. But others, like Ryszard Kapuscinski, found their own ways of telling a similar sad tale.)

Among other Ozymandias-like delusions, Mobutu had built a vast palace and airstrip capable of receiving a Concorde jet, set in the jungle at Gbabolite, and untold millions more were secreted abroad. In the meantime, rebellions in the eastern part of the nation broke out and two terrible civil wars, complete with child soldiers and rape as a tool of control over subject populations, coupled with invasions by armies based in Rwanda and Burundi, all contributed to the disorder, destruction and death on a monumental scale.

Eventually, Joseph Kabila, succeeding his assassinated father, Laurent Kabila, took control and ruled for 18 years and, then, to the surprise of many, announced in 2018 that there would be elections for a new president and parliament — and that he would not run. In a near-miracle, the country actually held an election on 30 December, and it took place largely without bloodshed.

Kabila had originally taken charge in 2001 and he had ruled the country ever since. First elected in 2006 and then again in 2011, amid claims of fraud, he should have left office in 2016 in response to constitutional limits, but he postponed elections and tried to tweak the constitution in his favour instead. Kabila’s reign, like his predecessors’ times in power, has been marked by accusations of graft and cronyism in the impoverished nation, to the extent he risked sparking more violence — such as the kind that had erupted in December 2017 after he initially refused to step down — if he did not leave office.

By the end of the poll, several provinces did not actually cast votes, reportedly on instructions by health authorities, warning an Ebola epidemic could be spread further by gatherings at polling stations. (There remains a bit of confusion as to who, precisely, decided to put off that polling, and rumours persist it was meant to tamp down the tally in support of opposition to Kabila’s designated successor.)

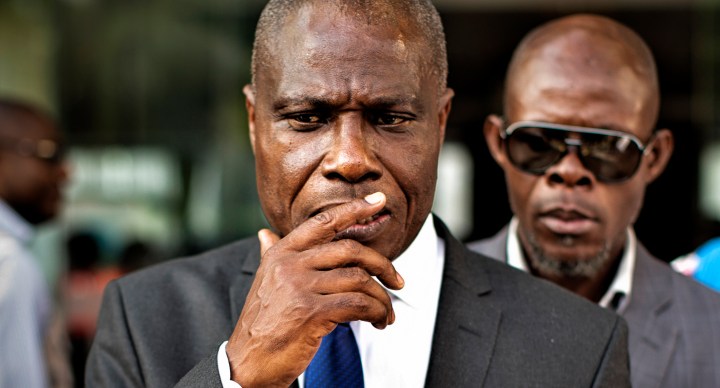

By 10 January 2019, the country’s electoral commission had initially declared Felix Tshisekedi, the leader of the main opposition party, had won the election with just under 39% of the vote. Almost immediately, Martin Fayulu, head of a second opposition party, charged that the result was “rigged, fabricated and invented”. Meanwhile, the Catholic Church — which had placed more than 40,000 election monitors at polling stations all across the nation — claims Fayulu actually won by a convincing margin instead. Kabila’s handpicked successor came third.

Tshisekedi is the son of the longtime opposition leader, Etienne Tshisekedi. Tshisekedi the younger had initially decided not to run in the election — opting originally to join a united opposition. Ultimately, however, he went with his own bid for national leadership, with a platform of leadership to tackle the country’s immense poverty amid great mineral wealth.

Given Tshishikedi’s unexpected ‘victory’, not surprisingly, there are suspicions that his surprise win — after polls had indicated Fayulu was at the pole position — meant Tshisekedi had reached a quiet, backroom power-sharing deal with Kabila. That would continue to give the current president and his cronies access to some of the wealth from the country’s extraordinary mineral reserves.

Besides the mineral resources noted earlier, the DRC is also one of the world’s leading suppliers of coltan. Coltan, or columbite-tantalite, is the mineral from which niobium and tantalum are extracted. Tantalum is crucial for electric car batteries and tantalum capacitors for electronic products. Revenue from coltan mining has contributed to the financing of several of the DRC’s deadly conflicts, and human rights abuses such as child and forced labour are common in its mining.

The Roman Catholic Church was particularly engaged in this election. Given its share of the population of around 40%, and the fact that it runs so many of the nation’s schools and hospitals, it is seen by many as a moral anchor amid so much governmental thievery and corruption. Several years ago it had brokered the ultimately failed deal between Kabila and protesters, and during 2018 it has become a major anti-Kabila force acting to establish a democratic practice.

The National Episcopal Conference of the Congo (CENCO) had marshalled the more than 40,000 election observers to watch like hawks over voting throughout the nation. CENCO announced its tallies had shown that an absolute majority of the votes cast had actually gone to Fayulu rather than Tshisekedi.

Part of the question of who won (or who fiddled the ballots) may reside with arguments over the voting mechanisms, with the current government using an electronic voting system that was — apparently — not entirely fraud-proof. As a result, Fayulu has now taken his dispute to the country’s constitutional court for a ruling. In the meantime, both France and Belgium have indicated they have some questions about the results and French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian was also quoted suggesting Fayulu was the real winner.

Meanwhile, the UN Security Council had taken up the issue for some initial debate, and in a Sunday morning briefing, South African Minister for International Relations and Co-operation Lindiwe Sisulu aimed at clarifying her government’s position and refuting criticism South Africa had been fence sitting on the election’s legitimacy. She explained there would be further discussions and determinations at the Security Council once the observer group presented its final report at the beginning of February.

Working to position her comments in line with positions taken by SADC – the Southern African Development Community – Sisulu had argued that the Security Council should be encouraged to send mediators to the DRC, once the final tabulations are publicly announced and certified. In the interim, she commended the DRC for having achieved a peaceful election. Or, as she said:

“When you consider that there more than 600 political parties participating, 12,000 candidates for the parliamentary election, and the fact that it is the first comprehensive election in the DRC since its independence, and there may have been one or two incidents, but it was a peaceful outcome.”

Asked how much credence the South African government (or SADC for that matter) gave the CENCO concerns, the Dirco minister said the Security Council had taken the unusual step of hearing from CENCO as well as the observer mission, and the UN representative in the DRC in order to hear all sides and views. She added it was still premature to make any final judgments, and she would be guided for the future discussions, given South Africa’s capacity as Africa’s representative.

Meanwhile, a statement issued by Zambian President Edgar Lungu, operating as chairperson of SADC’s Organ of Politics, Defence and Security, called on the DRC’s politicians to consider a negotiated political settlement for an all-inclusive government.

As the statement read, “given the strong objections to the provisional results of the presidential election in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Southern African Development Community has called on all political leaders to consider a negotiated political settlement for an all-inclusive government. And SADC encourages all stakeholders in the DRC elections to pursue a negotiated political settlement for a government of national unity”.

The SADC statement went on to quote Lungu:

“SADC draws the attention of Congolese politicians to similar arrangements that were very successful in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Kenya where governments of national unity created the necessary stability for durable peace. SADC, therefore, encourages all parties to enter into a political process towards a government of national unity in order to enhance public confidence, build bridges and reinforce democratic institutions of government and electoral process for a better Congo.”

Interestingly, absent from the media briefing, but contained in the SADC note, was a rather strong acknowledgement of those CENCO concerns, adding that SADC “feels a recount would provide the necessary reassurance to both winners and losers”.

And so we are left with charges by the Roman Catholic Church in the DRC that there had been a seriously flawed, Chicago-style ballot; there are complaints by the ostensibly losing candidate, Martin Fayulu, to the DRC’s constitutional court to ask them to invalidate the results; a UN that awaits its final report from its own observer mission before making a firm recommendation; and a SADC report encouraging the winners and losers to join hands in a government of national unity, a GNU. (A GNU, regardless of who won, might seem to obviate the need for national elections in favour of peace and stability — even if a GNU becomes the cockpit for squabbling over who controls which part of the DRC’s mineral patrimony.)

This balloting in the DRC is not over by a long shot, not least because the country has never actually had a peaceful transfer of power following an election and there is simply no experience with it. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider