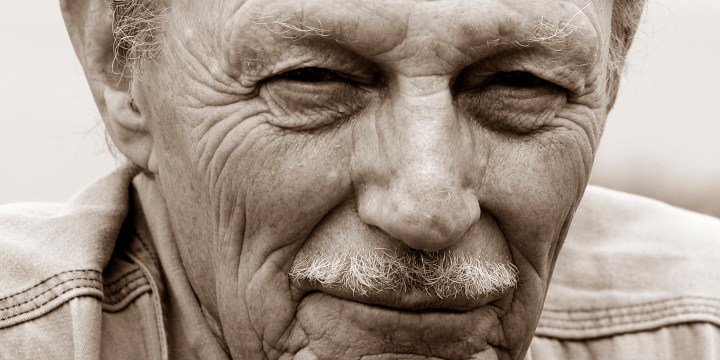

Harvey Tyson, 1928 – 2018

‘Unsinkable’ editor who always took his job seriously, but never himself

South African newspapersman Harvey Tyson died on Friday, 30 November 2018, aged 90.

Harvey Tyson lived to see the second volume of his two-part autobiography Behind The News published. His son Craig, himself a journalist and acclaimed former magazine editor, said his father had been discussing the book, End of the Deadline, which had only gone on sale the week before, and other books he still planned to write, right up to the end.

He died in Hermanus in the early hours of Friday, on his daughter Helen’s 59th birthday, surrounded by his wife and his children. He was 90 years old and had been suffering from cancer for some time.

Perhaps the best known of all the editors of The Star — he was its second-longest-serving editor — Tyson was at the helm when the paper celebrated its centenary in 1987 and would go on to oversee its highest circulation, just shy of a quarter of a million copies a day.

Born in Johannesburg and educated at Kingswood in Grahamstown, followed by a year at Rhodes University, Tyson spent more than 40 years in journalism on nine newspapers; starting at Kimberley’s Diamond Fields Advertiser, before moving to the Pretoria News and then Durban, where he would become assistant editor of the Daily News and then assistant editor of the Cape Argus. He would also spend two sojourns in Britain working variously for the Yorkshire Press, the Kentish Press, The Scotsman and the Times of London.

He left journalism for a short time to work for the Chamber of Mines in Johannesburg in their communications department before being headhunted back as the deputy editor of The Star in 1970. He succeeded John Jordi as editor, when Jordi literally died at his desk, in 1974 — beginning what would be a highly celebrated 16-year tenure as editor and latterly editor-in-chief of the Star, Saturday Star and Sunday Star.

To celebrate the paper’s centenary in 1987, at the height of the apartheid regime’s repression, Tyson arranged for the highest profile colloquium yet on press freedom, “Conflict and the Press”, to be held in Johannesburg, drawing international media luminaries such as Katherine Graham of The Washington Post and legendary British Sunday Times and The Times editor Harold Evans, and supported by newspapers in 17 countries including from behind the erstwhile Iron Curtain, prompting the ire of apartheid president PW Botha.

In 1990 he was jointly awarded the SA Union of Journalists’ highest honour for “defending the press’s freedom in its most threatened hour”. He stepped down from The Star that same year, handing over the editorship to Richard Steyn. Tyson was appointed to the board of the Argus Printing and Publishing Company for the last years of his career, when he also wrote the seminal Editors Under Fire, a treatise of newspaper publishing and editing under the apartheid security legislation. On retirement, he took up a directorship at what is today Meropa Communications, but continued to write throughout, publishing books, contributing to other books and living life to the utmost.

He climbed Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest peak, becoming at the age of 67 the oldest at that stage to summit via the difficult and very dangerous Western Breach route. He rode the Argus Cycle Tour for the first time at 80, having already taken part in 10 Tour de Farce’s, a European cycling expedition made up of former editors of The Star — Steyn and Peter Sullivan — the last editor of the Rand Daily Mail, Rex Gibson, who served afterwards as Tyson’s deputy editor-in-chief on The Star and long-time Star columnist and author James Clarke, who was the chief instigator of the Tour de Farce. He also competed, albeit without any great degree of success, in the Roof of Africa car rally at least 10 times.

“He was unsinkable,” remembered Steyn, who was hand-picked to replace him at The Star. Steyn had got to know Tyson when Steyn was editor of the Natal Witness.

“The thing I remember most about him was that he always took his job immensely seriously, but never himself; journalism was a serious passion for him.”

South African journalists, Steyn said, would forever be in Tyson’s debt for working with the then chair of Naspers, “Lang Dawid” de Villiers, to get the NP government to back down from its determination to have all journalists in the country licensed.

Gibson said Tyson had been a man who was never afraid to try something new or different.

“When I left the Rand Daily Mail I was uneasy about going to The Star, but I was never asked to modify my opinions on anything I wrote in the seven years I spent at The Star. That tells you a lot about Harvey and his real intentions because I was slightly more liberal than he was.”

Peter Mann, the chair of Meropa and night editor of The Star under Tyson, said he had been a fantastic editor.

“He was much better than he was ever been given credit for, very thoughtful and incredibly brave.”

During the worst of the states of emergency, The Star had a major from the Security Police stationed in the building with the power to stop the presses if anything undesirable was published.

“Harvey would say: ‘It’s the easiest thing in the world to get closed down,’ but the trick was to get away with publishing things the government didn’t want.”

It was one thing, said Mann, to be an activist paper and get closed down, but another thing altogether to be a big internationally respected metropolitan daily and still let the readers know what was happening all the time.

To that end, Tyson would publish blank pages in protest, with warning notes in the middle of the page or at the end of reports, he’d publish nursery rhymes poking fun at the government, among other ruses to warn readers that what was being published was heavily censored or had been done under duress.

“I had endless respect for him, he was wise and thoughtful, a lovely human being with a huge sense of humanity.”

Sullivan, who became editor of The Star after Steyn, agreed.

“He loved politics, he loved newspapering, he was constantly curious with an absolute sense of integrity and ethics that governed everything in his life.”

There were two moments of Tyson’s editorship that stood out for him, he said.

“The first was the leader that called for whites to abstain from taking part in the referendum for the tricameral Parliament. I wrote that editorial on his instruction.”

The editorial would forever tar Tyson with the sobriquet: “The editor’s indecision is final”, something that was picked up and pushed by rival editor Tertius Myburgh of the Sunday Times.

Nothing could have been further from the truth, said Sullivan.

“Harvey decided very emphatically that for whites to vote on something that blacks were excluded from — and therefore giving it a stamp of approval — was absolutely abhorrent and he wouldn’t be part of it.”

The second moment was when Tyson was given tapes of the Reverend Allan Boesak in flagrante.

“Various papers didn’t use it. Harvey and I were the only ones in the entire Star conference who decided to use it — the rationale was simple. Boesak had just been elected leader of 80 million Christians as the president of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches. He owed his position to being a moral leader, yet here he was caught acting immorally.”

The other conundrum, said Sullivan, was the source of the incriminating material — the security police themselves. Tyson’s solution was unique — and scrupulously fair.

“He divided the front page in two, top to bottom. On the one side, we ran the sex scandal, on the other a denouncement of the dirty tricks campaign.”

Looking back on his career, Tyson wrote in The Other Side:

“I confess that I’ve been in a jail… though that’s pretty common these days. In fact, I have boasted a longish criminal record. But seldom have I admitted that I slept with a nun. Some people show considerable interest and scepticism when I do confess it. Yet it is a fact. More than once a young and beautiful nun invited me into her bed which I shared with her through each night in her own nunnery.

“Once I shared — briefly in pitch darkness — a canoe with a caiman more than 2,000 miles up the Amazon. It happened in the legendary Black Lake with the pink dolphins. But that’s unlikely to interest you.

“What else?

“As a young newspaper reporter, I became, for some inexplicable reason, the momentary confidant of one of the heroes of the Boer War, the Great War, and the Second World War – who is better remembered as an author of the founding documents of the League of Nations and, 25 years later, of the United Nations – the only person in the world to sign both treaties.

“I speak of General JC Smuts. That is a small memory which I treasure, as is the finer and greater honour of conversing with that greatest of statesmen, Nelson Mandela, on private and public matters before he was everybody’s leader as president of South Africa and understandably the friend of every person in the world by the time of his death.

“Of considerably lesser interest for you should be the peculiar fact that I happened to meet all of South Africa’s prime ministers and presidents of the past 60 years, from Drs DF Malan, HF Verwoerd and ‘Lion of the North’ JG Strijdom, to BJ Vorster, PW Botha, FW de Klerk and Thabo Mbeki, as well as Roy Welensky, Hastings Banda, Ian Smith, Kenneth Kaunda, Robert Mugabe and other leaders of nations south of the Sahara. But that’s because it’s merely part of what I did for a living. This entire list may not be worth one discussion you might have been privileged to share with a true friend and incandescent freedom fighter, Helen Suzman.

“While deliberately name-dropping, I suppose I should mention that I also met one of the nicest of US presidents, one of the wittiest of British prime ministers, as well as most of the polite crowned heads of Europe from Sweden to Spain and many boring heads of state from Italy to Istanbul.

“What else? The only other experiences with which I can try to catch your interest are some of my moments of terror:

“Facing the drawn guns of East Germany’s Vopos, the people’s police, behind the Iron Curtain. Being totally lost without papers or money or any form of verbal communication in Red China shortly after the Tiananmen Square crackdown. Being stranded in Belgrade in similar circumstances on the edge of war in Bosnia. Staring at death in the eyes of the long-horned ‘lion-killer’. Or staring into the scorpion pit of a Sultan’s prison beyond the road to Samarkand.

“Or staring at Jesus, in a moment of bewilderment, in a house of ill repute.” DM

Tyson is survived by his wife, Arlene and three children from his first marriage to Colleen; Craig, Helen and Barry, all of whom were journalists at some stage; two step sons Nick and Anthony Yell and grand-children Kate, Ty, Lucy and Holly. The funeral will be held at the United Church in Hermanus at 11am on Tuesday December 11 and will be open to all.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider