TELEVISION REVIEW

The Vietnam War: The Darkest Heart is Collective

Ambitious in scope, PBS’s The Vietnam War, now showing on Netflix South Africa, is comparable to the legendary World War II series, The World at War, which riveted viewers.

Many of the best historical documentaries illuminate not only the event they’re reporting on, but also encourage audiences to reflect on the time they’re living in. Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s comprehensive 18-hour documentary series, The Vietnam War, is an unflinching portrayal of a doomed war that tore not only into Vietnam, but into the psyche of America. In exposing the fault lines between the militarists and the peaceniks (the conservatives and liberals in the US have been at loggerheads since their Civil War in 1861–1865) the series underscores what is arguably the most pressing issue facing global societies: the polarisation of the right and left.

The Vietnam War is an impressive attempt to understand what drove the conflict. The answer is complex, and the series explores how a potent mixture of ideology, blundering politicians, ignorance, arrogance and economics coalesced to create – and intensify – the devastating confrontation. Beginning with the brutal French invasion and occupation in 1865, it offers an analysis of the roots of the war. For the most part, the French colonists treated the Vietnamese as sub-human – who can forget Catherine Deneuve as Éliane in Indochine whipping her workers on the rubber plantation? As with so many of the struggles for independence from European colonisers, the Cold War cut through Vietnam.

Burns and Novick contemplate how the US got embroiled in the war, and unpicking this is the focus of the first episode. The US involvement spanned several presidents (both Republicans and Democrats), and the series tackles them all: Harry S Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower – through John F. Kennedy’s assassination to the relentless lunacy of the Lyndon B. Johnson years. In a curious twist, it’s revealed how Nixon’s Watergate scandal had its genesis in the Vietnam War. After the ignominious end to Nixon’s presidency, it would be Gerald R Ford whose short term brought the war to its dramatic and bitter dénouement.

Overall, the US involvement is an illustration of the old proverb “pride comes before a fall”. Washington seemed assured that their victory against communist Ho Chi Minh (a former US ally under the Japanese rule) and his Northern Vietnamese forces would be swift. The US Achilles’ Heel was their overconfidence, which was tied up with their legendary idea of themselves as exceptional. They underestimated their enemy. They didn’t understand how deeply the roots of nationalism were embedded in the Vietnamese psyche. Having shaken off a series of vicious colonisers (including the Chinese, French and Japanese), many Vietnamese were in no mood for more foreigners – do-gooders, hut-burners, bombers or otherwise – in their country.

As with many conflicts, both sides were flawed. Like South Africa today, South Vietnam’s government was dominated by a corrupt ruling elite, and while the middle-classes had a good life, the lower classes were excluded from economic benefits. Under these conditions, socialist ideals blossomed into communist aspirations amongst the dispossessed, and the guerrilla resistance movement of the Viet Cong began fighting for their rights in the South. While the series tends to paint Ho Chi Minh in a sympathetic light, his communist comrades in North Vietnam were little better than the incestuous, corrupt South Vietnamese leadership. Authoritarian and merciless, the eventual communist victory plunged the country into the ruthless Soviet style land reform and punitive re-education.

The US anticipated that their excellent technological advantage would win the war. It didn’t. The haunting pulsing of helicopter blades whipping through the air is the opening sound effect on episode one. As the rugged, mountainous, jungle terrain of Vietnam was tough to navigate, the US relied on helicopters to traverse this treacherous and often impenetrable landscape, and the Vietnam War assumed the moniker of The Helicopter War. With their superior air power, the US military leaders believed that tossing enough bombs, Agent Orange and napalm on Vietnam and its people would eventually break their spirit. The bombing statistics given in the series are astounding. More bombs were dropped on Vietnam than were deployed during the entirety of World War II. Instead of crushing the communists, the relentless bombings simply strengthened their resolve. And resolved they were. There’s remarkable footage of the North Vietnamese support troops (mostly women in this case) speedily repairing the legendary Ho Chi Minh Trail after yet another US bombing spree had cratered sections of it.

In this helicopter war, the bodies of US soldiers were airlifted out for burial. The Vietnamese were not afforded the same privilege – their resources needed to be directed into fighting. While a small percentage of US families didn’t get their loved ones back for burial, most Vietnamese families have never been able to find and bury their nearest and dearest. Many didn’t even know if relatives or friends had died – they lived in a grim state of limbo, hoping they might some day return.

Unable to hold any area for long, the desperate US politicians eventually began to callously calculate their military might through body counts. The death statistics are simultaneously enlightening and horrific. While 58,000 US soldiers died, their ally, South Vietnam, suffered the loss of 250,000 soldiers. Over a million North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers perished, and the series estimates that two million civilians from North and South Vietnam were killed.

Sobering statistics for a war that has primarily been told through a US lens – admittedly to English speaking audiences. Burns and Novick attempt to remedy that; while the majority of interviewees are from the US, they also interviewed many Vietnamese from both the North and the South. Through giving the Vietnamese voice to tell their own story, the complexities of this shattering civil war can be pondered. It’s the human face of the war, and the true power of the series is that it facilitates a space for those who were involved (directly and indirectly) to speak of the horrors.

This enables viewers to empathise with the impossible predicament of the canon-fodder soldiers on all sides. Importantly, through these remarkable interviews the documentary breaks the toxic deadlock of communist versus capitalist by exposing the human beings behind the ideologies. If you’ve been economically disenfranchised or had your country repeatedly colonised by inhumane regimes, it’s reasonable that communism would become an attractive system of social organisation.

As a result of its empathetic portrayal of all sides, The Vietnam War is a significant cultural artefact. The only criticism is that more airtime could have been given to the Vietnamese, however, considering it was a US production primarily for US audiences, the weighting in the favour of the US is understandable. As Burns acknowledged in an interview with the New Yorker: “After ‘The Vietnam War,’ I’ll have to lie low. A lot of people will think I’m a Commie pinko, and a lot of people will think I’m a right-wing nutcase, and that’s sort of the way it goes.” Clearly it was a tough balancing act to draw in viewers from across the political spectrum.

The series excels in its unforgiving analysis of the US ruling elite. None of the presidents nor their Secretaries of Defence knew what to do about what was (from very early on in their involvement) a hot mess of an unwinnable war. Throwing more military might at the situation simply didn’t produce results. Nor did their calculated strategy of “winning the hearts and minds” of the South Vietnamese populace. It’s impossible to win hearts and minds when you don’t know who your enemy is. The nightmare for the US soldiers was never knowing who was for them and who was against them. The Viet Cong wore no uniforms and their guerrilla tactics kept the US and their South Vietnamese ally back-footed. Of course, winning hearts and minds was never going to be successful when the homes and rice supplies of suspected Viet Cong sympathisers were routinely set alight.

There were atrocities on both sides. All-American men, brought up on a diet of Church and principles, were sent off to mow down or be mowed down – all in the name of God and capitalism. John Musgrave, a US veteran astutely observed how he dehumanized the enemy by thinking of them in derogatory terms; it was a process which enabled him to kill without remorse. He calls this strategy “Racism 101.” Another US veteran, Matt Harrison, admitted that what the war revealed to him was that “the veneer of civilisation is very thin.” Indeed. As Bao Ninh of the North Vietnamese Army says, “Who won and who lost is not a question. In war, nobody wins or loses.”

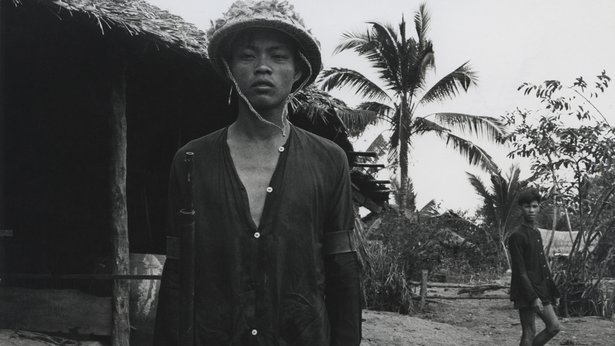

The Vietnam War, Episode 6: “Things Fall Apart” (January 1968-July 1968). Photo from www.pbs.org

What is disturbing is how cluelessly gung-ho the US presidents and their advisers were. It’s hardly a palatable picture of competent leadership. While Lyndon B Johnson was the president who signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law, he emerges as the most Hawkish of the lot. His deepening involvement in the war – and his “fake news” statements to the public – created mayhem in the US.

The journalists reporting from Vietnam – the series tends to focus on Neil Sheehan and a few others – revealed a different narrative to that of the political elite. The discrepancies between the official account and what the reporters were exposing plunged the US into a domestic crisis, and ultimately The Vietnam War depicts two countries at war with themselves: Vietnam and the US. Some of the most thought-provoking material considers what it means to be a patriot – how our ideas of what patriotism is shapes our world view, and by association structures what our responsibilities are to our nation, our ideologies, and to humanity.

There’s so much that can’t be covered in this review. A few highlights: how Robert McNamara demanded a daunting amount of data; even the data dumps Washington received didn’t lead to victory. The racism explicit in the US was transported across the Pacific and was rife amongst the US soldiers in Vietnam. Minority groups were initially over-represented in the war – a fact that fuelled much of the anti-war sentiment in the US; sending society’s most economically vulnerable out to fight for the integrity of capitalism was an irony not lost on the anti-war protesters. At some point, Jane Fonda makes an appearance as a murder-mouthed peacenik. The series suggests that Nick Ut’s famous photo of the naked 9-year-old Napalm Girl – her name is Phan Thị Kim Phúc OOnt – turned the tide of the war. It’s fascinating that much of the US public was unable to humanise their enemy. It was the dedicated journalists who documented the war that brought the US involvement to a controversial end. It wasn’t an easy loss for the South; their communist enemies were tyrannical victors.

As a video editor, for me some of the real artistry in The Vietnam War is expressed in the impressive, creative cutting. While the time it must have taken to compile and organise the mammoth amount of archive material (photographs and footage) and to structure the storylines in terms of particular markers in history is impressive, the series is cut with a heady vitality. It’s an 18-hour documentary marathon constructed of archival material and interviews, and it’s never boring. Key to this is the immersive sound design.

The soundtrack features iconic songs from the era, including hits from The Animals, Bob Dylan, Procol Harum, Jimi Hendrix, The Temptations, Janice Joplin and The Beatles (to name very few of the big names). Topped off by Peter Coyote’s assured narration of Geoffrey C. Ward’s well-researched script, the production is exceptional and rates as one of the best historical series I’ve watched. It is however relentlessly dark, and due to the heavy subject matter, I had to stagger some episodes over two viewings.

Beneath its surface, the series reveals that ideological dogmas – such as a belief in communism or socialism or capitalism – are often the result of social conditioning. Our upbringing and the ideas we’re exposed to, often governs how we perceive ourselves and our enemies. Chillingly, perhaps the entire war is best summed up as: their brainwashing versus ours. What we do for our collective beliefs is dark indeed.

Ultimately Vietnam was a war which shattered the US sense of their own exceptionalism. Arguably, the shame that began with Vietnam, culminated in Trump.

From 1966 to 1989, apartheid South Africa fought its own shattering version of Vietnam on the border of Angola and Namibia – what was then the South African protectorate of South West Africa. The South African nationalists fought against the communists. It’s sobering to watch The Vietnam War knowing that the many of the horrors of South Africa’s border war haven’t been comprehensively aired or acknowledged. Much like the Vietnam War, the veterans live in a shamed silence, living with the agony of having seen how painfully thin “the veneer of civilisation” is. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider