BOOK REVIEW

Ton Vosloo’s book has lessons for today’s political journalists who actively take sides

The debate over whether Naspers’s Ton Vosloo and his allies supported the more ‘enlightened’ apartheid thugs misses the point. The gravest sin of the Afrikaans media was not what it said but what it systematically hid from its public: the forced removals, the prison torture, the slave working conditions, the censorship, the petty segregation, the daily humiliations — all the conditions that defined apartheid and made it so horrifying to the rest of the world.

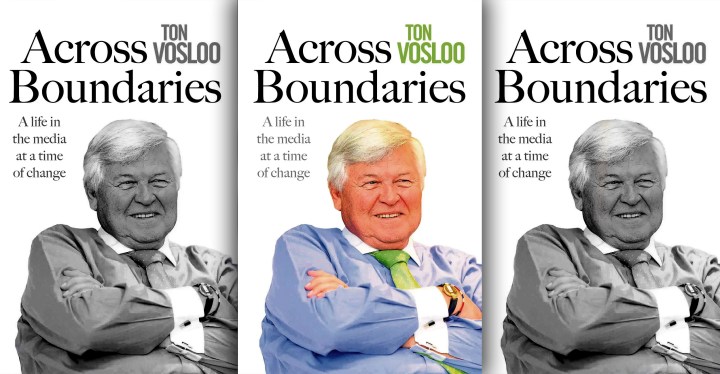

There is a throwaway line that made me gasp while reading Ton Vosloo’s autobiography, Across Boundaries: A life in the media in a time of change, launched in September 2018.

In 1989, Vosloo — then managing director of what was still Nasionale Pers (and today is Naspers) was central to the National Party’s internal battle for power between State President PW Botha and the new party leader FW de Klerk. In the book, he tells of a conversation with FW:

“The press statement FW wanted to make was in line with a draft statement I had read out to him earlier.”

Vosloo, as head of a media company, was drafting statements for the leader of a political party. He adds, enigmatically: “FW greatly appreciated our ardent support and friendship,” without telling us how the president-elect showed this appreciation.

It was never a secret that Vosloo’s Nasionale Pers was close to the National Party government. The company was started in 1915 as part of the Afrikaans nationalist “baaskap” project. Cabinet ministers sat on its board and its senior political writers attended closed party meetings. But the deep intimacy of the relationship and the detail of how the journalists and editors were compromised, is still salutory.

Vosloo loomed large in South Africa’s media for more than four decades, during which time he was editor of Beeld, managing director of Nasionale Pers and finally chair of Naspers. He can claim much of the credit for leading the company out of its parochial, ethnocentric roots into the global giant it is today, by a long way Africa’s biggest company and still growing.

Vosloo was at the helm when the company moved into pay-TV, spread across Africa and listed on the stock exchange. And he can claim credit for appointing and backing Koos Bekker, who took the company into the digital era and made it a global player.

It is disappointing then, after a life of such good fortune and successful leadership, that this avuncular figure — known for his generosity and benignity — should be unable to come fully to terms with the role he, his newspapers and his company played during apartheid. Vosloo argues repeatedly — almost too often — that his newspapers’ support for the verligte arm of the NP led the way to its final victory and enabled FW to release Mandela and begin negotiations.

He makes much of a 1981 column in which he raised the possibility of negotiations with the ANC. This was hailed in international media as an admission from within the ruling party that its policies were failing. Indeed, these were bold words in the context of the Afrikaans media. But a close reading of the column shows him saying talks could only happen if the ANC “would undergo a purge in respect of its behaviour pattern”.

In other words, one could talk to the ANC if it ceased to be the ANC, and he sneered at those — such as parliamentary opposition leader Frederik van Zyl Slabbert — who would talk to black leadership on its own terms.

Beeld under him developed “the reputation of a trendsetting daily whose reformist agenda paved the way for radical political change,” he says. There is truth in this if you stay within the laager, and compare yourself to the far rightwing papers, but it is an absurdity if you look at it in a wider context.

He reminds us — with regret — that as late as 1987, he fired Fairlady editor Dene Smuts because of the political coverage she began offering in the magazine, even though she did little more than acknowledge there might be political life beyond the NP. This was at a time when the country was aflame with insurrection and the political momentum had shifted decisively from the Union Buildings to the township streets and the factory floor. And the company forced out its much-respected chair, Lang Dawid de Villiers, for the unforgivable sin of supporting an independent (non-NP) parliamentary candidate.

Although Vosloo retells these decisions with regret, it is hard to credit the company for the forward-looking policies and open-mindedness that he claims for it when they were demonstrating that it was still intolerable in the late 1980s to stray beyond the narrow and already-doomed confines of the ruling party.

Indeed, his papers were vitriolic in their condemnation of the Afrikaners who went off to meet the ANC in the historic and breakthrough Dakar talks of 1987. While Vosloo is honest enough to describe this as a “mistake and an embarrassment”, that is as far as he will go.

The debate over whether Vosloo and his allies supported the more “enlightened” apartheid thugs misses the point. The gravest sin of the Afrikaans media was not what it said but what it systematically hid from its public: the forced removals, the prison torture, the slave working conditions, the censorship, the petty segregation, the daily humiliations — all the conditions that defined apartheid and made it so horrifying to the rest of the world.

These were barely reported in his newspapers, leaving them with the legacy of having encouraged the wilful myopia and ignorance that enabled the perpetuation of the barbaric conditions of apartheid which still mark and divide our country.

Vosloo could not bring himself to go the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to deal with this, and this led to a bitter internal fight with 120 of his journalists who — under the leadership of the brave Tim du Plessis — did so. Each said with great eloquence what Vosloo could not — and still cannot — quite say:

“I was blind and deaf to the political aspirations, anger and suffering of my fellow South Africans. I… did not properly inform readers of the injustices of apartheid… I offer my sincerest apology and fully commit myself to prevent the past from being repeated.”

This book should have been an important accounting of the past, of a proud and respected Afrikaans leader coming to terms with the horrors of apartheid and his and his institutions’ central roles in it.

Instead it is another sad monument to the half-hearted acknowledgement by many white South Africans, incapable of accepting responsibility for the treatment of their countrymen and women, and the deep and ugly scars it has left across our landscape.

Still, this book should be read by today’s political journalists, many of whom have become as obsessed as he was with the arcane and tortuous internal shenanigans of the ruling party, and have little hesitation in actively taking sides in internal battles and shifting with the slightest of breezes. The result is the poverty and pointlessness of much of our political coverage.

Vosloo’s book is a reminder of the roots of this journalistic insider culture, and what a dead-end it is for reporters and editors. DM

Across the Boundaries is published by Jonathan Ball (2108).

Harber is the Caxton Professor of Journalism, Wits University

Become an Insider

Become an Insider