Op-Ed

What ensures sporting excellence?

Fernando Alonso’s imminent retirement from Formula One inevitably draws comparisons with the sport’s greats. Considered to be one of the best of his generation, many suggest that the Spaniard’s two F1 World Championships, remarkable by anyone’s measure, sell his talents short. His record, and his retirement, provides an opportunity to ask what makes sportspeople excel and realise their true potential?

One recent survey of Millennials asked what their most important life goals were. Nearly 75% responded that a major objective was to get rich. More than half said that another goal was to become famous.

Compared to Baby Boomers (born 1946-61), GenX’ers (born 1962-81) and Millennials (born after 1982) considered goals related to “extrinsic” values (money, image, fame) more important and those related to “intrinsic” values (self-acceptance, affiliation, community) less important. In 1978, being rich ranked eighth among all the goals listed as choices. Since 1989, this goal has consistently ranked first.

Yet an ongoing Harvard study of adult development which has surveyed a group of (initially) 724 men from different social classes for 75 years shows, however, that it is our relationships with family, friends and community that keep us most healthy and happy as we go through life.

There is more to realising one’s sporting potential than having the drive and determination to succeed, to become famous and perhaps even rich. As in life more generally, success rests on choices and relationships.

Motorsport is a hi-tech pursuit. Thus reward is disproportionately skewed towards those who have access to the best team, effective aerodynamics or fast and reliable equipment. But how do they find themselves in that position? And there is more to success in the sport than simply having the best equipment or being the best driver.

What separates the likes of three-time World F1 champion Ayrton Senna, four-time champion Alain Prost and seven-time champ Michael Schumacher from others is their ability to get others working to their goals. Application is crucial; champions are the last to leave the garage. This helps to not only build a technical knowledge, but to get the team behind the driver.

This relates to communication abilities with the team, and with sponsors and the press. In a social media age this is perhaps now more necessary than ever. But having an active Twitter profile or Instagram account, or even a cool merchandising brand, is not enough. There is a need to separate oneself from the crowd in part by being personally positive and constructive in building friendships and relationships that can provide crucial support and mentorship.

Language skills are also important: English, German, French and Italian are commonly spoken up and down the pits.

Such communication, technical and mental attributes were discernible even in Senna’s second F1 season with Lotus. His then team manager, the cynical veteran Peter Warr, was astonished by the Brazilian ace’s technical capacity.

“His approach was basically,” notes Warr in Tom Rubython’s magisterial account of Senna, “to sit down with the engineers, confirm that things he was expecting to be done to the cars had been done, and talk about the set-up. He would spend a lot of time on tyres and he would work out a programme, in conjunction with the engineers and myself, of what we wanted to try in practice, how we wanted to try it, when we wanted to run full tanks, how many laps we would do on this, that and the other and so on.”

Senna’s powers of concentration were legendary, as was his assuredness, determination, single-mindedness and intellectual abilities, and maturity.

Motor racing is (in)famously a sport of excuses, in which the families behind the drivers seldom encourage honesty, preferring, naturally, to point to the fault of others over “their” driver.

Yet the importance of self-belief aside, humility is required in spades, inwardly if not publicly, to be able to address one’s faults. This quality is usually underpinned by acute self-awareness. This relates to the imperative to continuously and realistically assess one’s own goals — setting them neither too high or too easy. If necessary, change one’s goals and have a Plan B: Just like one of us (Emanuele) shifted from a focus on F1 to touring cars and ultimately to Le Mans sports-cars.

Planning and strategy are bywords for career management, longevity and versatility. Part of this demands, too, acquiring the skills and education for a life after your chosen sporting career.

A sense of timing helps. There is a need to be present in the right place at the right time with the right skills, as Schumacher proved for his sensational debut at Spa in 1991 when the Jordan car’s regular driver, Bertrand Gachot, was brought before a court to answer a charge of assaulting a London cab driver.

Of course, like talent, there is a need for fitness. This demands keeping abreast of modern training and techniques. Similarly, be on your best behaviour all the time. Be nice to the nerd: what goes round inevitably comes round.

Most sponsors and teams have a highly tuned bullshit meter. Credibility demands solid results; winning and then stepping up, rather than shooting for the stars and failing. The mindset should exude positivity and focus on “how can I improve” rather than “what I didn’t have”.

Motorsport is peculiar, given the concentration of financial and technical resources. But the same human qualities — honesty in identifying and learning from mistakes, building and nurturing relationships, communication with your team and others — apply to other sports, such as cycling.

Again, personal skills on and off the bike, an ability to learn, education and a supportive system are necessary components.

Nic White, a former pro cyclist who has turned his hand to managing and training the next generation, advises his young riders that “perseverance is key, and pays off in the long run”.

“There are no short cuts. Cycling is also about ups and downs, and you may fall off, have a setback or similar, but true character is what makes a rider return to his level, or ability and move forward (as has been the case with Daryl Impey, Chris Froome and so on).”

But, he adds, “Staying humble is also necessary: you may be on top on one day, but the very next day, you are right at the back again, having to fight your way up!”

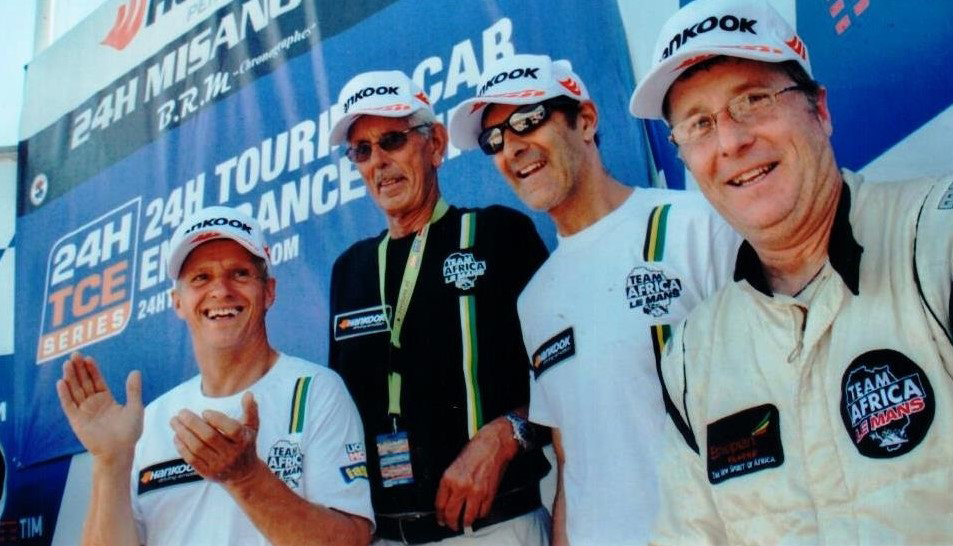

Team Africa Le Mans Third Place, Misano 24-Hour Italy 2017 Jan Lammers, Sarel vd Merwe, Emanuele Pirro and Greg Mills

In his autobiography The Climb, the four-time winner of the Tour de France (and St John’s College alumnus) Froome details the moment his career took off — the 2011 Vuelta, when he finished second. A combination of his own physical and mental maturity, better training, getting to the bottom of a lingering illness (in his case, bilharzia), and a more supportive team environment made the difference. Team Sky was a step up from the comparatively careless Barloworld, and light years away from the bureaucratic bottom-feeders who ran the Kenya national cycling team at the expense of the athletes.

Jock Boyer, the first American to ride the Tour de France in 1981, has been the coach and manager for more than a decade of what started as Team Rwanda, and has grown into Team Africa Rising. He has had to confront all manner of challenges in building an African cycle team from scratch, including creating a base of technical, organisational and other skills.

“From the outside looking in it seemed that the state of the equipment would be my biggest challenge. But it was not.

“My riders had at the most only a few years of education. They had survival skills and not much else. This would surface in the failure to understand inertia and brake at the bottom of hills, lug big gears and wonder why they were dropped by riders going at a much higher cadence, training and eating regimes… Regardless of the innate talent that is present in Rwanda, and elsewhere in Africa, a proper, wider education is essential to cycling success.”

Similarly, Douglas Ryder, the Dimension Data cycling team principal, highlights the need for a holistic approach, encompassing physical activity, biomechanics, mental energy, nutrition, recovery, life infrastructure and decision making. And, he notes, “culture, whereabouts, history in the sport all play a huge role as well as the life-changing events of what success means to the individual”.

Impey, the first South African to hold the Tour’s coveted yellow jersey, in 2013, and a professional for the last decade, says that learning from failure is a key element in his success.

“I have,” he says, “been through many tough periods on and off the bike but they have driven me to be a better athlete. It is easy to take talent for granted and once you see that you might not be able to exploit your talent again it makes you realise that you love cycling and racing and the challenges it brings. You can only be truly successful if you push through the hard times. Failing is part of the process,” he observes.

“If you are open to learning from your mistakes and try not to make them again then it’s already a small success.”

Fernando Alonso seemed to have a knack for changing teams just as their fortunes dipped. Senna and Prost, by comparison, were not only at least as good as Alonso on the track, but always put themselves in the best position with the team, as did Schumacher.

Mark Twain said: “Keep away from those who try to belittle your ambitions. Small people always do that, but the really great make you believe that you too can become great.”

Just as it would help for others to get behind you, it is important to mobilise them, too, to your ambitions. One tip here for the younger generation is to replace some screen time with people time.

Of course there is no substitute for hard work. As Nic White recalls from his time as an aspiring professional taking the hard road in Europe, is “to ‘push hard on the pedals’ – which comes from the Flemish expression: Hard op de trappers duwen, jonge!”.

But such effort is easier, in sport, as in life, if you are doing it because you like it, regardless of fortune or fame. This will not only likely ensure a long career, but a great deal of fulfilment whatever the level and successes achieved. DM

Dr Mills heads the Johannesburg-based Brenthurst Foundation, is a board member of cycling’s Team Africa Rising, and has authored eight books on motorsport, including most recently Saloons, Bars & Boykies; Pirro is a former F1 driver for Benetton and Scuderia Italia, a F1 test driver for McLaren, and a five-time winner of the Le Mans 24-hour race for Audi. Both were, a long time ago, go-karting rivals and champions with big dreams.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider