OP-ED

Graeme Williams vs Hank Willis Thomas: Acceptable artistic appropriation — or just plain old theft?

A prominent American artist has been accused of stealing and profiting from an image taken by a South African photographer in 1990, weeks after Nelson Mandela was released from prison. The image of a group of black children taunting armed white policemen symbolised the sudden shift of power in the country in the final days of apartheid. Photographer Graeme Williams was astounded to see his photograph, massively enlarged and drained of colour, in a work signed by Hank Willis Thomas and exhibited at the Johannesburg Art Fair.

In the muted, murky colours of the vintage photograph, young black kids are kicking up their legs in a loose-limbed and joyous adaption of the toyi-toyi, the southern African liberation movement march/dance/statement. They are dressed in an array of possibly hand-me-down clothes and oversized, weary shoes except for the child leading this little band; he is barefoot. Another of the boys is leaning back as he dances along, looking up at a squad of young men dressed in dull blue uniforms. The policemen sit atop a giant armoured vehicle; most of them are looking off to the right. They do not look like they are about to break out in dance any time soon.

“It must’ve been so confusing for them,” recalls Graeme Williams, “because they were convinced of their rightness and that the job that they were doing was righteous and patriotic, whereas these little kids just look like they are having a big jol and it’s just that sort of the looseness and freedom of the kids compared to the sort of hunched body language of the cops.”

The image appears to be a symbol of its time and place: Thokoza township in 1990.

“That particular visit was quite vivid because it was such a short time after Mandela was released… we’d waited so long for this kind of moment to happen. There was a real powerful feeling of excitement and the sense that change was imminent… and there was no turning back to apartheid.”

When Barack Obama was running against the late John McCain in 2008, Newsweek magazine ran a significant piece in which they asked each candidate to discuss what best depicted their world view. Obama (or members of his team) chose Williams’ image from Thokoza, combining it with an extract from a speech he gave, “There is a struggle going on! A struggle that demands we choose sides. It’s a choice between dignity and servitude. A choice between right and wrong.”

That image does indeed have an uplifting quality, a sense of joy even if the viewer is unaware of the history of police in Casspirs looming above small black children. Williams was covering the rally, and key to the assignment was to get Nelson Mandela interacting with his supporters. It is easy to forget that even being in possession of a photograph or likeness of Mandela had been a criminal offence a year before — Mandela’s image was a sought-after commodity in the news world. Once Williams had made photographs of Mandela, he looked around, searching for what attracted him beyond the obvious news shot.

What he saw was, he says, a simple and clean shot with a fairly obvious message.

“You just frame an image and it comes from an instinctual point rather than rather than a kind of intellectual (process).”

“The image is compositionally straightforward: it’s a classic composition of thirds. You know, where you’ve got the image dominated by the police in the top third and the top of the fence cuts the image into top and bottom halves… the obvious separation between the cops and the toyi-toyi-ing kids.”

There is more to the image, the cops are almost all looking to the right of the frame and out, while the kids are looking left, into space.

“They’re looking into the future and the cops were looking at a dismal future… and the children dancing into their future. It is kind of interesting and you wonder where their life paths have gone, but there is this wonderful innocence and the apparent lack of fear of those cops in the Casspir.

“But there’s no ways you can take all that in at the time and that is why so few images actually last, because a whole lot of factors that come into play in order to make them work on multiple levels. I can take credit for a bit of instinct but the rest there was a lot of luck and it was good timing!”

Besides Obama, others recognised the iconic nature of that image. On Williams’ Facebook page of 7 September 2018, he wrote:

“Last night at the opening of the Johannesburg Art Fair, I was disturbed to find a displayed image of mine credited to another photographer. By slightly whitening part of the image (possibly some comment on whiteness vs blackness) African American artist, Hank Willis Thomas has attempted to make this image his own.

“My unaltered image has been published and exhibited many times. In 2008, as Barack Obama sought the presidency and raced for the position against John McCain, Newsweek magazine ran a story asking each candidate to discuss what best personified their world view. This image that I took in Thokoza (1990) during a Nelson Mandela rally was used to illustrate Obama’s world view.

“Thomas is quoted as saying: ‘I do think appropriation is akin to stealing, even though I think the ownership of advertising images is questionable. But for me it would feel more like stealing if I thought ‘I really wish I’d taken that image myself so I’m just going to use it.’

“Well Hank, I am glad that we agree on that point.”

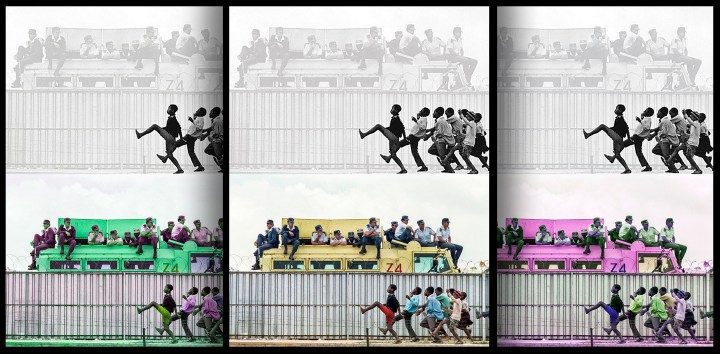

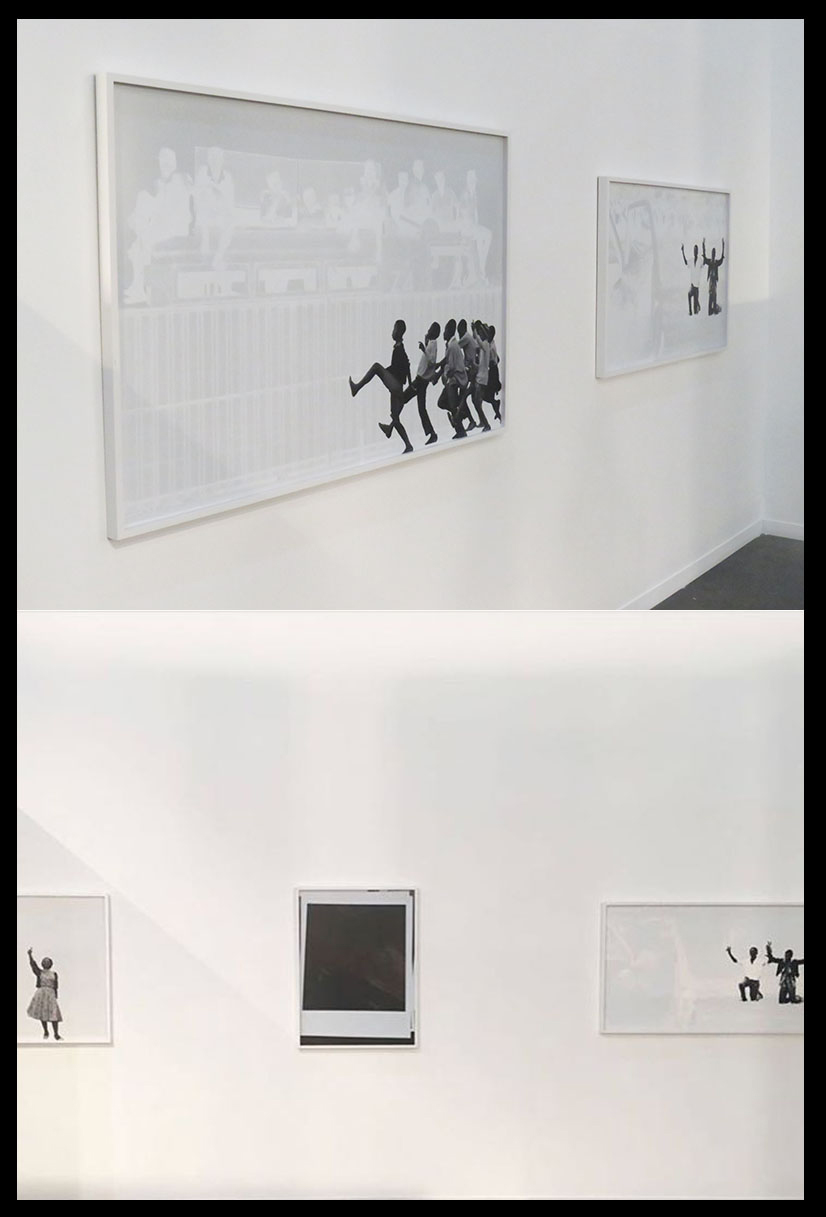

William’s appropriated image is a massively enlarged copy wherein the dancing children have been desaturated and the rest has been smeared with a chalkish white; whitewashed. There is no credit to be seen as to who the original photographer and copyright owner is.

Thomas did not approach Williams for permission to use the image. It would seem from interviews subsequently granted that the US-based artist does this regularly. He has appropriated news images from Peter Magubane, Alf Kumalo and Ian Berry. Thomas says he regularly uses images from the Drum magazine archive for his pieces. There has been a spate of articles on the subject.

The original image by Graeme Williams.

‘ By slightly whitening part of the image (possibly some comment on whiteness vs blackness) African American artist, Hank Willis Thomas has attempted to make this image his own,’ says photographer Graeme Williams.

When Neelike Jayawardane approached Thomas, she writes that he rather disingenuously said:

“Questions of presentation, representation, ethics, appropriation, commodity, ownership, authorship, exploitation, and subjectivity have been raised within the field since its beginnings and will be into the future.” Indeed, they have, but not in any way to support what he has done and is doing in appropriating/stealing/borrowing with permission.

The Goodman Gallery quickly took down the work, but refused to admit that there was any wrong involved. Thomas eventually offered to leave the appropriated work with Williams for a year, so he could live with it and then decide if he wanted to destroy it — together. Perhaps Thomas was thinking of how to get more publicity out of this theft. Williams declined — he has the original version to live with.

Charl Blignaut in City Press wrote:

“Asked why he never sought Williams’ permission, he said: ‘This is not a new issue and it was already made when I realised it was his. I work with archives around the world, in this case mostly with the Baileys [African History] Archives.’ ”

American copyright law makes greater allowance for what is termed free use and according to the principles of fair use Thomas says:

“I’ve altered it enough to make a new work. If he doesn’t agree then that’s a grey area right there. I also think about other grey areas like does the photographer always get permission from the subjects they photograph? Why can I not use an image of people at a public event at a moment that changed history? Who can claim ownership of the people in the image?”

Could Thomas be implying that Williams should somehow have sought permission from the subjects in a news image from a public place, and further that Williams has thus exploited the subjects? Does this mean that he, Thomas, believes he is somehow righting the historic inequalities of apartheid by making a lot of money from selling an image he has no legal or moral rights to?

It seems Thomas is implying that the children have been deprived of their rights by the photographer, this implicating him in the apartheid system. And to really interrogate that implied blow for justice, can Thomas answer why he has also appropriated works by black South African photojournalists like Ernst Cole, Alf Kumalo and Magubane (who incidentally spent nearly two years in solitary confinement, courtesy of the apartheid regime)?

Thomas has likened what he does to sampling or remixing, but fails or chooses not to note that the original artist gets a percentage of royalties from a subsequent remix. Thomas also told City Press that Williams must “take the money, take the image, I won’t reproduce it”. – Williams has declined that too.

Money makes everything ugly, of course. The weirdness of an art world that exhibits the American derivative of an appropriated, or borrowed, or stolen (choose your term) image from recent South African history for the asking price of $36,000 when the original photograph has never been sold for more than $1,200 makes one’s head spin. It is as if a great moment captured in a certain sometimes prosaic and democratic medium needs to be re-interpreted by someone who speaks the jargon of the art world to ensure it is properly valued.

The best part of this entire debacle is that it has allowed many more people to see this quite fantastic and timeless image. Not that many news images find a second life as a timeless and universal rebuttal of oppression and pessimism. It is exciting when a photographic work transcends its original mandate as a communication of the moment, a news event.

“It is the simplicity of the message that has kind of given this image longevity and meaning to South Africans,” says Williams.

In the original news image, one sees that the entire photograph seems to have been smeared with mud; to have a kind of dull, grainy coating.

Williams recalls that the films from that day were “processed in three-day old chemicals. And I was a hopeless colour printer”.

“I would tell them (the picture desk editors) that the drum scanner was getting the colour wrong and that they should fix it in London.”

The history of the image intertwines with the lore of a working photojournalist shooting day after day in a war zone; occasionally glimpsing, and successfully recording, a sliver of the irrepressible human spirit. DM

© Greg Marinovich 2018, photographs copyright Graeme Williams 1990/2018

Become an Insider

Become an Insider