Special report

Justice Delayed: The TRC Recommendations 20 Years Later

October will mark 20 years since the TRC’s (Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s) final report, and with it comes a fair amount of reflection and criticism. Here, Brian Mphahlele, an unknown hero of the struggle, awaits the justice he was promised, and former TRC investigative head, Dumisa Ntsebeza, reflects candidly about his retrospective view on the process.

October 29 will mark 20 years since the TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission) final report’s recommendations were handed down to the newly elected ANC government. Many people have evaluated the shortcomings of the TRC, and criticised the lack of results from the commission’s ultimate inability to deliver restorative justice. The promises of the TRC are still in the process of being delivered. Most recently, the National Prosecutions Authority (NPA) announced that they will reopen 15 TRC related cases to pursue prosecutions.

Included in these recommendations are specific guidelines for financial reparations to victims, a list of over 300 perpetrators of apartheid who should be prosecuted, and specific steps for restoring dignity nationwide and equalising the playing field in a country grounded in massive inequality.

While hope remains that some of these recommendations may one day be realised, there are victims who slipped through the cracks, and still suffer significantly from trauma they personally endured during apartheid.

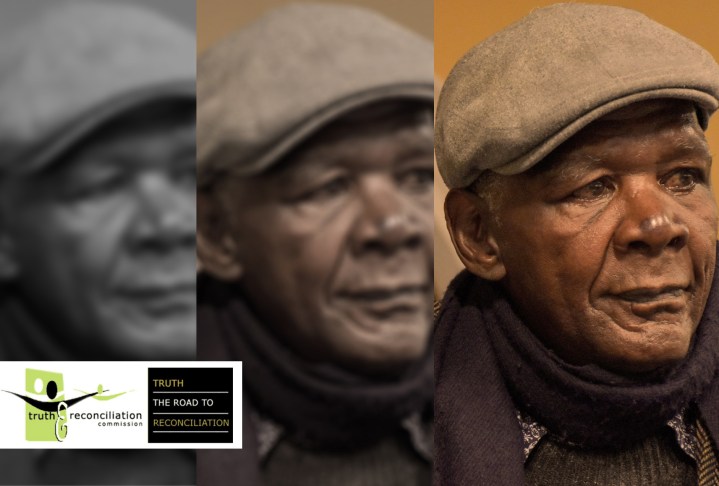

Brian Mphahlele

Brian Mphahlele awaits financial reparations for injustices he endured during Apartheid. Photo by: Adam Yates

Struggle fighter Brian Mphahlele believes the least the government can do to restore dignity to the victims of apartheid is to pay reparations in the amount the Truth and Reconciliation Commission initially recommended. Mphahlele, who was incarcerated for ten years during apartheid, sustained significant physical, emotional, and psychological damage from living in captivity. In the 26 years since apartheid ended he has received free psychological treatment but only one direct payment from the government, totaling R30,000.

Mphahlele can remember details with astounding accuracy.

He recalls both significant and insignificant dates in his lifetime with ease. He knows where he was when he listened to the Beatles benefit concert for Bangladesh. He can describe the emotional impact Steve Biko had on him when they first spoke.

He can paint a picture of the crowd that surrounded the courthouse before he received his prison sentence. He can pinpoint the exact hour in the morning in 1977 when the police surrounded his home and rounded up him and his brothers. He is haunted by an image of a hooded figure in the back of a police car that identified him, causing his capture. He knows on what floor of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission offices he officially described the injustices he suffered during apartheid.

And he vividly remembers where his incarceration, his torture, his physical and psychological damage all began. On 11 August 1976 when he found himself surrounded by fire.

On that day in August, the Cape Town education protests in Langa had turned violent. Stores and schools were engulfed in flames. Just two months after the famous Soweto uprising, the students in Cape Town took a stand against Bantu education and the Afrikaans curriculum.

On 11 August, Mphahlele played a central role in the protests. “I made petrol bombs,” he admits. While courageous in his fight, his choice to take a leading role in the protests forced him to go on the run. For three months, Mphahlele was trying to come up with a plan to escape the country. But in early January of 1977, he awoke late at night to loud knocks on his front door. Police officers had surrounded his home as part of a widespread community raid looking for anti-apartheid activists. Mphahlele was captured and put on trial.

The trial lasted 14 days. Mphahlele’s ultimate conviction for arson resulted in a 10-year long prison sentence which he fully served.

The first four years of Mphahlele’s imprisonment were at the Allandale Correctional Centre, the final six were at Block F on Robben Island. During this time, Mphahlele was the victim of constant abuse. He spent a significant amount of time in solitary confinement. He was often beaten, electrocuted, and tortured, sustaining irreversible brain damage.

“Mr. Mphahlele was a victim of apartheid State security branch; he was subjected to severe, unspeakable horror of torture including long periods of solitary confinement,” states a letter from the Trauma Centre where Mphahlele received six years of treatment. The letter continues, “It was however that due to the torture coupled with psychological sensory deprivation… resulted in him suffering from post traumatic stress disorder… While we could work with improving his social adjustment and build communal support… the organic damage to the brain cannot be altered.”

The TRC set out to restore dignity to people who suffered like Mphahlele. Many of the commission’s recommendations from its final report have yet to be delivered.

Nearly 30 years since his release from prison, Mphahlele holds his head high. While some days he can’t scrap together enough money for a taxi fare, and he spends hours waiting at a public hospital to get glaucoma eye drops, he remains motivated and on days he can afford it, hopeful as well.

The battle Mphahlele is currently fighting, and one which he has been fighting for 23 years, is to receive reparations for victims of apartheid. “I don’t want to give up,” Mphahlele explains, “good reparations can help you restore your dignity.”

Mphahlele looks around the country and sees poverty, violence, and crime. He sees significant groups of people that are disillusioned and demoralised by the government. “People have lost hope in a government that has made false promises.” The false promises Mphahlele is referring to are those regarding reconciliation and reparations.

In a life altered by tragedy and torture, Mphahlele caught some initial breaks when it came to the TRC. When Mphahlele first went to the TRC, reparations hadn’t even crossed his mind. “I never thought of reparations [during the struggle]. All I was fighting for was freedom. So people can live freely. Peace and harmony, that’s all.”

Mphahlele reflects, “I [went to the TRC because I] needed psychological help.” At the time, in the mid 1990s, Mphahlele’s undiagnosed PTSD was debilitating. He made his statement to the TRC and was immediately recommended to a trauma centre. He received years of free medical and psychological help for his injuries. He is one of the 21,676 officially identified victims of apartheid. And he is one of the 17,408 that have received reparations in the form of monetary payment from the government.

An excerpt from a medical letter detailing the impact of Brian Mphalele’s incarceration on his health.

However, Mphahlele finds the one-time payment of R30,000 “an insult to us all.” Former South African President Thabo Mbeki, “never went according to the [TRC recommendations],” recommendations that, if followed, would have provided Mphahlele with annual payments of R30,000 for a period of six years.

Mphahlele knows these reparations would have been transformative for him, but he has resigned to acknowledging that the past is the past. His voice tenses when he recalls the government closing down the TRC with R850-million still left for distribution to apartheid victims. Money that was said to go to supporting infrastructure, a task that “nobody asked for,” according to Mphahlele.

That fund has now grown to R1.5-billion. And Mphahlele will continue fighting until that money is distributed to people whose lives were irreparably damaged by inhumane treatment of the apartheid regime. There is a suffocating sense of abandonment felt by Mphahlele, one that is shared by thousands of apartheid victims who are still awaiting reparations.

Despite his frustration, Mphahlele remains hopeful. His face glows when he talks about his tight-knit community in Langa, where walking down the street everybody knows one another. He imagines a country in which those in power start caring about poor and vulnerable populations, a time where there is free quality healthcare, free education, and affordable housing options for all.

“As a person who has fought and sacrificed his life for this country, I am a wounded man, I am a broken man,” laments Mphahlele. He pauses, to carefully choose his words before continuing. “I did not fight for liberation [so that] at the end of it I will be driving a Ferrari. No, my struggle was, and is still, never laced with greed and corruption. It’s not. All I want to see is people living happily, living in harmony. The apartheid years are over. We always pray that it must never happen again in this country or anywhere in the world.”

He pauses again, letting the weight of the words ring true out loud.

“Yeah, I think that’s all I have to say.”

Dumisa Ntsebeza

Dumisa Ntsebeza remains proud of his work in the TRC, but frustrated with the ANC’s treatment of recommendations. Photo by: Adam Yates

Who’s to blame? While there are a series of criticisms for the TRC itself, a former commissioner, Dumisa Ntsebeza believes the real blame lies elsewhere. When investigating the content of the recommendations, Ntsebeza argues, it is clear that what unfolded after the TRC’s conclusion is a distant reality from what the commissioners recommended.

When Dumisa Ntsebeza was named as a commissioner to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission he was not particularly thrilled.

“I had done everything to discourage them from appointing me,” he recalls. “One of the reasons is we found it difficult to come to terms with the whole process was the amnesty provision.”

The now infamous amnesty provision was a central component of the TRC. It promised amnesty to all those who perpetrated violent acts during apartheid, assuming they testified and met certain criteria. Those criteria were that they told the truth, they provided all relevant information, they proved they were acting with political objectives, and that they applied for amnesty within an allotted time period. A time period that was pushed back twice to allow for more applicants. If the defendant met all these criteria, they were granted amnesty and shielded from further prosecution.

However, once Ntsebeza accepted the position to head the investigative section of the commission, the committee became very important to him. He hoped the commission would restore dignity by legitimising the voices of victims in giving them the opportunity to share their stories.

When people criticise the TRC, or the delay in action following the TRC final report, what they’re really doing is falsely empowering the commission with a capacity Ntsebeza believes they never had in the first place.

He explains, “I don’t know why people scapegoat the TRC. [I’d imagine] some scapegoat because their knowledge of the TRC is superficial and flawed.”

One continuous criticism of the commission is the fact that it was incomplete.

According to Marjorie Jobson, the National Director of the Khulumani Support group, there are about 80,000 people that have never even been recognised as victims of apartheid because they weren’t able to offer a formal statement to the TRC.

“One of the gravest injustices in South Africa is that we’ve closed the door on thousands of victims,” Jobson says. Khulumani has been collecting data related to apartheid victims for 23 years and the organisation has amassed a massive database of statements and victim stories.

Jobson iterates a series of flaws in the TRC statement collection process. These problem include an excessive focus on urban areas, standardised guidelines for statement collection that ostracised certain victims, and, perhaps most glaringly, the closing down of statement collection after a mere 18 months. To this day, victims who did not manage to come forward during the TRC are still unable to do so in any official capacity.

“Time was not on our side so we then realised we can’t do, and shouldn’t pretend we did, in-depth reporting,” Ntsebeza contends. “It was intended to be a broad brush against the canvas [we wanted] to have everyone that emerged from such a dark place put forth a sample of what it was like, a sample of compelling evidential value.” Not the “universal panacea” some believe it to have been.

Ntzebeza admits that the TRC deserves blame for some of the language in the preamble that may have given the wrong impression about the TRC’s wherewithal, but it is a “false nomenclature” to call the TRC a reconstruction of society. Ntsebeza states that “Our mandate was to investigate with [the goal] of completing as complete a picture of the years between 1960-1994 as possible.” In order to do so in the time they had, the commissioners could not speak to every victim and hear every story.

At the end of the day the TRC was a beginning not an end, says Ntsebeza. There is still “unfinished business” in the reconciliation process. Furthermore, he thinks that the recommendations were specific, seriously developed, and could have made a major impact in the restoration of dignity to apartheid victims. If the suggestions were followed, South Africa, Ntsebeza believes, would be a different place today. “There was no political will, the new democratic government didn’t hold up their part of the bargain.”

In Dumisa’s eyes the ANC government, not the TRC itself, deserves the blame.

“On 27 October 1998 we get an application brought by ANC President Thabo Mbeki interdicting over the handing over of recommendations.” This symbolic act, two nights before the TRC recommendations were supposed to go public, served as an immediate red flag to Ntsebeza.

“To me, that was symbolic of how there was noticeable and demonstrable disconnect between the Madiba legacy and the [new legacy] that was manifesting itself… [The ANC] wanted the final report to not be published so whatever they though detrimental to their support would not be known.”

Investigating the content of the report backs Ntsebeza’s claims that the work of the commissioners seems to have been ignored.

The report itself

There are 46 pages of recommendations at the end of the TRC final report. The recommendations were in “regard to the creation of institutions conducive to a stable and fair society” as well as “recommendations concerning any matter with a view to promoting or achieving national unity and reconciliation”.

The recommendations span a variety of topics, such as healthcare, business, the environment, and the economy. The recommendations are ambitiously optimistic for the vision of a new South Africa, yet the recommendations for prosecutions and reparations seem reasonably attainable.

Ntsebeza recalls the directive in the TRC report was that “Anyone who did not apply for amnesty and those who lied… should be prosecuted ASAP.” However, due to orders from the ANC, no prosecutions were pursued. “We did not prosecute TRC related cases because of political pressure, ANC politicians said don’t prosecute these cases,” Ntsebeza remembers.

The text of the actual report reads: “Where amnesty has not been sought or has been denied, prosecution should be considered…. The commission will make available to the appropriate authorities information in its possession concerning serious allegations against individuals.”

The TRC suggested around 300 perpetrators of human rights violations to prosecute. Until the recent NPA announcement to prosecute 15 cases from this list, there had been only one person found guilty of apartheid-era crimes, Eugene de Kock. The recent resurgence in TRC related prosecutions is a welcome sign that this recommendation may be realised, albeit slowly, and twenty years after it was first suggested. The cases of Ahmed Timol, the Cradock Four, and others are currently being litigated. Many hope that the fifteen new cases taken on by the NPA will be the start to a long process of prosecuting the full list from the TRC report.

In addition to prosecutions, one of the central recommendations from the cumulative TRC report, financial reparations for victims, has yet to be realised as well. The final report offered recommendations for reparations in five different categories. Urgent interim reparation, individual reparation grants, symbolic reparation, community rehabilitation, and institutional reform.

“Without adequate reparation and rehabilitation measures, there can be no healing and reconciliation,” states Volume 5, Chapter 5, Article 21 of the TRC report. “Comprehensive forms of reparation should also be implemented to restore the physical and mental well being of victims.”

Individual reparation grants were recommended alongside other forms of financial compensation to restore dignity to victims of apartheid. Article 41 explains the purpose of the cumulative grant money as to “acknowledge the suffering caused by the gross violation that took place… enable access to services and facilities and… to subsidise daily living costs, based on socio-economic circumstances”.

When evaluating the actual roll-out of these grants, it becomes clear that among other unfulfilled promises, the South African government has failed to sufficiently provide financial reparations to a significant portion of apartheid victims.

The financial reparations that have been distributed remain far below the initial recommendation made by the TRC. Section 26 in the final report, explains that grants are to be distributed “to each victim of a gross human rights violation… paid over a period of six years”.

The 17,408 victims who have received compensation were granted one-time payments of R30,000.

Jobson believes that the TRC was never about the victims and its main purpose was to organise amnesty. Jobson complains that the dismal reality of reparations is “not what the victims were [originally] told, and [it’s] not what the world sees”.

Ntsebeza points out that the TRC proposed a 1% market tax on companies in the Johannesburg stock exchange. This could have helped collect the money necessary for the R2,500 monthly payments. Ntsebeza shakes his head. “I can’t believe the ANC let these companies off the hook.”

In his eyes, the recommendations took into account the needs of victims, it was a refusal to act that pushed the restoration of dignity aside.

The tax could have raised multi-billion rand for the Presidential Fund for reparations, reasons Ntsebeza. “You can leave it to the imagination what that money could have done.” The money, Ntsebeza declares, was “not a compensation”. He continues: “It was something more intended be symbolic. A sense of dignity to look forward to something.”

Ntsebeza agrees with Mphalele. The once-off payment of R30,000 is an “insult”. From Ntsebeza’s perspective it is the government, not the TRC, that failed to do right by victims. “The question therefore must be asked why did the ANC do this? This jury is still out.”

Despite the purposeful disregard of the TRC recommendations, Ntsebeza is proud of the work the TRC accomplished.

“Did it succeed? No, the question that needs to be asked is what would South Africa have been but for the TRC. Every day for two years people were glued to their television, people were shocked by what was revealed.” Ntsebeza continues, “We now know more facts than what we would have known [without the TRC].”

Jobson believes that the validation of the victims’ stories and lives is a continuous process. “These are the people we have to honor, there has been no honoring, there has been blatant neglect for people who need reparations to overcome what they’ve been exposed to in the internal movement to resist apartheid,” declares Jobson in desperation. Jobson believes it’s time to remind South Africans of “the cost of people, of injustice, of apartheid”.

Regardless of arguments about who the TRC was for, whether the TRC succeeded in reconciliation, and how the TRC will be remembered, the truth of today is that more than 4,000 apartheid-era victims were promised financial compensation and have yet to receive a single rand. Families of over 300 victims were promised closure on the case of their attacked loved ones and are still waiting to see justice served.

The TRC was successful in its some of its aims. As Ntsebeza recalls with vivid detail, the simple act of having one’s story publicly validated, was a significant and meaningful step for all who were involved. Apartheid was an era in which proliferating misinformation created a fabricated narrative both nationally and globally about the reality of what was happening in South Africa. It is reasonable to dream that in the wake of the absence of truth, public declarations of fact would not just be a restoration of personal dignity, but would also be the first step towards national unity. However, the story does not stop there.

Ntsebeza agrees that the international narrative that the TRC liberated South Africans of their past and resulted in a fairy tale ending for a massive human rights struggle is false. The notion that, with Desmond Tutu at the helm, Christian values prevailed and forgiveness erased the trauma of 50-plus years of oppression, is also short sighted. However, as the 20th anniversary of the recommendations approaches, reflecting on the final report suggests that some of the failures to achieve reconciliation occurred only after the TRC closed.

In the meantime, the apartheid victims who fell through the cracks, those hoping for financial reparations, or those hoping for closure on the story of a loved one’s murder, continue to hope that justice will appear, 20 years delayed. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider