GIANT LEGACY

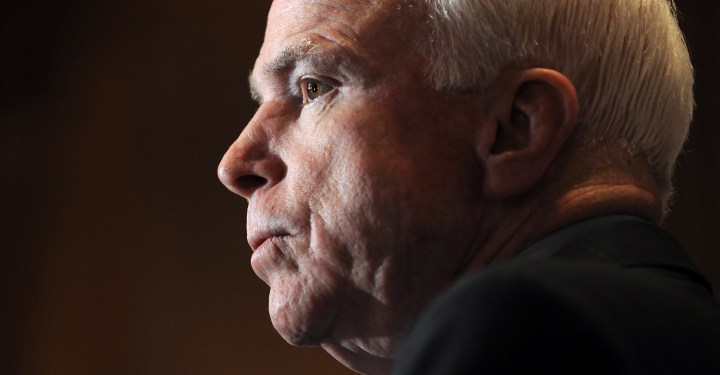

Remembering the complexities of John McCain, America’s maverick

The immediate reaction to US senator John McCain’s death within the context of the age of Trump brings to mind ongoing debates about Nelson Mandela and his legacy. Although McCain and Mandela are different politicians who lived in different countries, there are competing perspectives on Mandela’s legacy that illustrate the tension between how we want to and how we ought to remember politicians.

Last weekend, John McCain died at the age of 81, after battling brain cancer. Over the span of his career, he was an immensely influential Republican figure in American politics, for reasons that should be celebrated as well as criticised. Looking back on the scope of his career and influence is a reminder of the complexities of reflecting on a politician’s career in their moment of death, and the tension between how we want to and how we ought to remember politicians.

In American political culture, one in which myth-making plays an oversized role, McCain occupies storied ground. He served in the airforce during the Vietnam War and eventually became a prisoner of war (POW). Later, he served as a member of the House of Representatives, and then as senator, in the state of Arizona, for more than 35 years. He ran for president in 2000 and again in 2008, on the back of his popular persona as a maverick politician that he came to embrace.

American politicians tend to be viewed favourably after they die, but McCain’s persona seems to have enhanced the immediate hagiography of his legacy. McCain came to be known as a maverick for his experiences as a POW, the perception that he took on hardline Republican positions and for his candid demeanour and openness with members of the media. As a result, journalists have reacted to his death with immense sadness, lamenting the huge loss McCain represents in American politics — after all, McCain didn’t refer to the media as his “base” for no reason.

A significant portion of the praise being heaped on McCain, some of which tiptoes along the threshold of revisionist history, is a product of “the age of Trump”, a catch-all term that refers to the hyperpartisan, increased polarisation of American political discourse, and reduces otherwise nuanced events to their relation to US President Donald Trump.

In light of this praise, McCain’s death and the example his influence in politics leaves us with, is an occasion for reflecting on the importance of maintaining civility in politics, and the bipartisan allure of sticking to principles, not postures.

However, viewing McCain’s legacy through the lens of the age of Trump, obfuscates the consequences of the positions McCain took in American politics, and underlines the myopia of wanting to remember politicians in a certain light.

McCain’s criticism of Trump over the last two-and-a half-years seems to have prompted people to want to remember him as a maverick politician that favoured civility and principles, rather than a complex politician with flaws and shifting positions that we perhaps ought to remember him as.

His positions on immigration and foreign policy demonstrate the tension of these two competing frames. Despite the tendency of the Republican Party to paint immigration as a source of national anxiety, and as an economic burden, McCain repeatedly demonstrated his willingness to work across the partisan divide, and formulate a practical solution to a crucial issue that impacted tens of millions of people.

Despite these efforts, McCain’s position on immigration hasn’t always been so principled. During his 2010 senate re-election campaign, he supported the controversial immigration bill SB1070 in Arizona, which gave police the power to request immigration papers from arrested suspects. Moreover, that same campaign ran an advertisement calling for that “danged fence” along the border to be completed.

When it came to foreign policy, McCain was perhaps the American politician most supportive of military intervention. While the popular perception of the George W Bush administration is that it was filled with hawks such as Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, it was McCain and the gravitas of his maverick persona that generated bipartisan support and comforted Democratic politicians reluctant to openly embrace the military invasion of Iraq, the consequences of which also led to McCain supporting intervening in Syria.

To see McCain as a beacon of civility in the age of Trump can overlook the disastrous ways in which his appetite for military intervention was equally a part of his maverick persona.

But despite this aggression, McCain was also instrumental in restoring diplomatic relations with Vietnam and establishing relationships with some of his former captors from his time as a POW at the infamous Hanoi Hilton. He also repeatedly spoke out against the use of torture, because of its ineffectiveness in producing meaningful information and intelligence, and the ways in which it diminished the standards of American pride.

The development of McCain’s positions on immigration and foreign policy demonstrate that politicians hold positions that aren’t easily categorised. The terrain of politics is constantly shifting, which means the development of our understanding of politicians needs to be flexible enough to grapple with this complex reality.

The immediate reaction to McCain’s death within the context of the age of Trump brings to mind ongoing debates about Nelson Mandela and his legacy in relation to the Rainbow Nation. Although McCain and Mandela are completely different politicians that lived in different countries, there are competing perspectives on Mandela’s legacy that illustrate the tension between how we want to and how we ought to remember politicians.

Some people want to remember Mandela as a saintly figure that led South Africa to the promised land of democracy. Others want to remember him as a sell-out that eschewed total revolution for neoliberalism.

Both positions are aware of the volatility and vulnerability of the early 1990s, but are more grounded in relation to present challenges, which filter the ways in which we look back on Mandela’s legacy as either an example to be followed or denounced.

Time will tell if the trajectory of McCain’s legacy in American politics will follow a similar course. Whatever the case may be, when we try to contort the memory of politicians like McCain, to serve the needs or soothe the anxieties of the present, we run the risk of failing to learn from them. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider