THE PROMISED LAND

Fighting for the right to stay on the land where they were born

“Why do farmers inherit their father’s houses, but me and you can’t inherit our mother’s houses on the farm?”: It’s a question asked by Elizabeth Domingo, who was born on a pear farm near Ceres. Domingo lives with her siblings and their children in a house on Platvlei Farm, the only home she’s known. Her grandfather and mother worked the land and the family enjoyed security of tenure for decades. But when her grandfather and mother died, no other member of the family provided labour on the farm and as a result they’re facing eviction. As the country continues the debate on land expropriation without compensation, the rate of farm evictions is not slowing for families who once enjoyed work opportunities and residence on agricultural land.

The dirt road that leads to Elizabeth Domingo’s house is muddy after the morning rain, the pear orchards that line the road are bare, only rain drips from their branches. She sits in her living room beside the fireplace, it’s unlit, but the smell of a recent fire to warm the house during cold winter evenings lingers.

“Why do farmers inherit their father’s houses, but me and you can’t inherit our mother’s houses on the farm?” Domingo, 45, asks, wringing her hands. She and her extended family live in a seven-bedroom house on Platvlei Farm and have been given until November to vacate the property.

“I have no idea what I will do, I don’t know where we’re going to go because money is something we really don’t have. [We will] probably stand on the street, or the municipality will come and put us in a shack… it’s a very sore matter,” she says.

Elizabeth Domingo lives on a farm in Ceres and is facing eviction by the farm owner. 13 July 2018. Photo: Leila Dougan

Domingo and her family have lived on Platvlei Farm in Wolseley, near Ceres, since 1974. She was born on the farm, as she says, “when I opened my eyes, I was here”. Her grandfather, Johannes Domingo, and her mother, Susanna Domingo worked on the farm. After retiring, both Johannes and Susanna acquired life rights to residence in the house, but these were personal rights which could not be transferred to their children after they died. Johannes passed away in 1997 and Susanna in 2013.

“My grandfather was a lovely person, he was the foreman on the farm, he built this farm from scratch… And now, after 44 years [the farm owner] says because not one of us works [on the farm], now we need to get out. I feel it’s unfair towards us. Your entire life you’re here. You don’t know another place, and now you need to leave? That’s not right,” she says.

The farm owners are represented by Van Wyk Van Heerden Attorneys in Paarl. Steph Grobler, an attorney at the firm, spoke to Daily Maverick about the case and says that the eviction has been done in line with the Extension of Security of Tenure Act of 1997. According to court documents, the farm owners attempted to “negotiate a settlement” with the Domingo family in 2015, which would see them either relocate to a smaller house on the farm or elsewhere in the area. Domingo insists that they were not offered alternative housing.

But the question remains: it is fair and ethical to evict people who have lived on a farm their entire lives, such as is the case of the Domingo family?

Grobler says that it is fair to evict the family as they’re a “self-sufficient household.” According to a social worker who was sent by the Witzenberg municipality to investigate the Domingo family’s circumstances, the household’s combined income is more than R20 000 per month and they can therefore afford to support themselves outside of the farm.

Naomi Betana is a paralegal co-ordinator at the Witzenberg Rural Development Centre. The organisation offers paralegal advice to those who cannot afford private legal fees. Betana is assisting the Domingos with their case and says that the state of the family’s bank account is irrelevant.

“We could also argue, [the land owners] have so much land, why don’t they give a piece of land to us? It’s an unfair statement, because the bank account of the Domingos has nothing to do with them… What is ‘alternative accommodation’ for them? A wendy house in the informal settlement?” says Betana.

The Extension of Security of Tenure Act was designed to protect people like Domingo, farm dwellers and farm workers, from illegal and unfair evictions. The law takes long-term occupation into consideration and declares that those being evicted must be given suitable alternative accommodation prior to the eviction taking place. The act acknowledges that unfair evictions lead to “great hardship, conflict and social instability” and that the law should “regulate the eviction of vulnerable occupiers from land in a fair manner”.

But Domingo is convinced that the law only assists farm owners to legally evict people who have nowhere to go and “alternative accommodation” means being dumped in a informal settlement far away from basic services, transport, work opportunities and health facilities.

(See previous article by Daily Maverick on farm workers who were legally evicted and placed by their municipality in to an informal settlement here.)

“ESTA is not for us, it’s for the farmers,” says Domingo. “Look at how these farmers are behaving now… [ESTA] only benefits the farmer, because now he’s getting it right to evict me”.

But there are serious misconceptions surrounding the case, Grobler says.

“This is where the misconception comes in right. It’s a very, very common misconception in ESTA, people believe that you gain a protected or life status to reside on a farm if you’ve lived there more than 10 years, but section 8.4 is very particular and very specific. It says you must have attained the age of 60 and have lived on the farm for more than ten years, and then you’re considered to enjoy a life right, you as that person who has that nexus, not your family,” says Grobler.

Platvlei Farm falls within Witzenberg municipality which is part of the Cape Winelands District. An hour and a half by car from Cape Town, the municipality is mostly known for wine, fruit and vegetable produce. Agriculture is a dominant employer in the region, which has high rates of inequality.

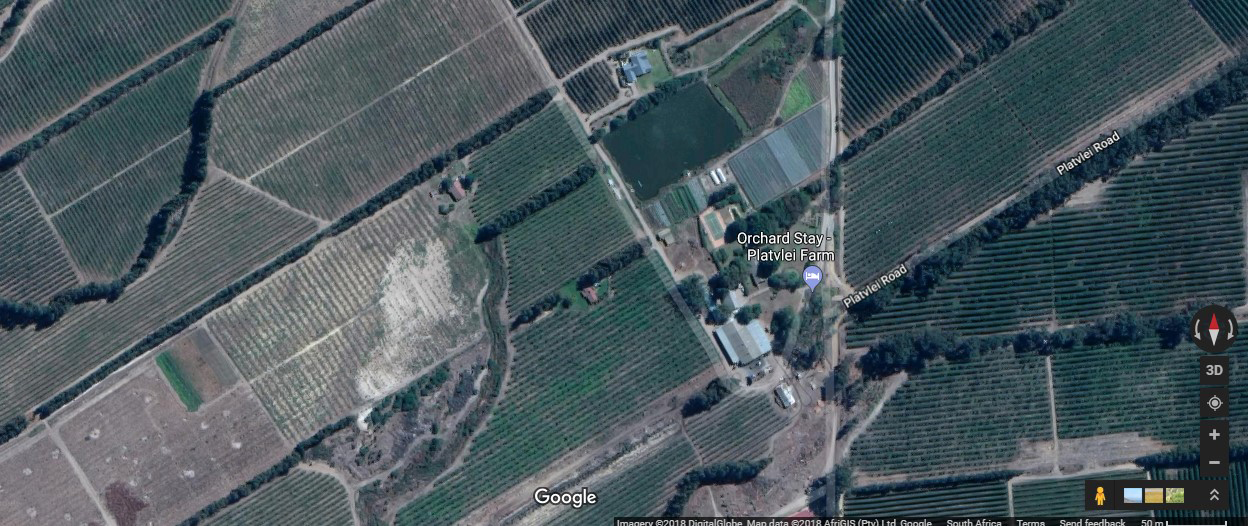

Platvlei Farm, in Wolseley, Ceres, where Elizabeth Domingo is currently being evicted from the home she’s lived in for over four decades. Courtesy of Google Maps. 23 July 2018

The municipality’s Integrated Development Plan for the 2018/2019 year, which outlines its long-term development strategy, says that illiteracy in the area sits at 36% and 18% of the population live in poverty. More than 5,000 residents are unemployed and with agriculture, forestry and fishing being the dominant employment sector, many residents rely on seasonal agricultural work or social grants.

Municipal manager David Nasson says that so far this year the municipality has received nine eviction applications. In these cases social workers are sent to the affected families to evaluate whether alternative accommodation should be provided by the municipality.

“Farm workers and especially children are very vulnerable and all evictions are extremely traumatic and emotional,” says Nasson. He says that there has been a rapid population increase in the area due to the growth in the agricultural sector. Witzenberg’s population has increased by over 20%, and the demand for housing has placed “immense pressure” on the municipality to provide services and resources.

Betana says that the municipality’s eviction count is far too low and there are a number of cases that they are not aware of.

The amount of poor people living below the poverty line in Witzenberg is sitting at 40% according to the municipality’s Integrated Development Plan. Over 50% of Witzenberg households fall into the low-income bracket and 6% of these households have no income.

At the ANC’s land summit held in Stellenbosch last month, farm worker activist Nosey Pieterse said that the Extension of Security of Tenure Act does not prevent farm evictions, rather it provides a process to evict farm workers legally without any consequences for farm owners.

“Government has failed farm workers,” he said. “Those who work the land have been reduced to Africans without their piece of Africa… some are fourth-generation farm workers are being evicted by first generation farm owners”.

He echoed sentiments by Domingo, saying that there is no appetite to develop housing on farms for workers and that farm owners would much rather evict farm dwellers and build “hokkies” in the townships made from “poles and a few iron sheets” leaving the farm whitewashed. “It’s a cleansing process,” he said.

Grobler raised concern about the narratives in the media that criticise farm owners and that agricultural land must be looked at from a commercial perspective, especially in the Western Cape where the sector provides job opportunities, generates income and “sustain[s] the food supply” in the country.

“[Y]ou can’t have every single child or grandchild of a protected occupant who is self-sufficient in their own right like in this Domingo household… have or lay a claim in terms of a real right and property to that particular household because at the end of the day, you’re going to have a really big problem with the economic sustainability of that farm,” she said.

Grobler also says that one of the reasons farm housing is so desperately needed is because current farm workers need a place to stay. “There’s only a certain amount of housing available on a farm, so once protected occupants have lived out their life rights, and they pass on, that house needs to become available for employees currently working on the farm.”

According to Grobler, having families like the Domingo’s occupy farm housing without them working on the farm could place significant strain on the farms economic stability. The reason is because new labourers who actually work on the farm need to be transported to and from work (at cost to the farm owner), as opposed to enjoying employment benefits such as housing. These labourers work “strange, arbitrary hours”and therefore need to live on the farm. In short, the Domingo’s should move on so that new employees can have the chance to live close to their workplace.

“If we want to ensure job creation, we want to ensure the fact that these farms in the Western Cape who do provide a lot of jobs, are able to continue exporting and contributing to the economics of this country,” said Grobler.

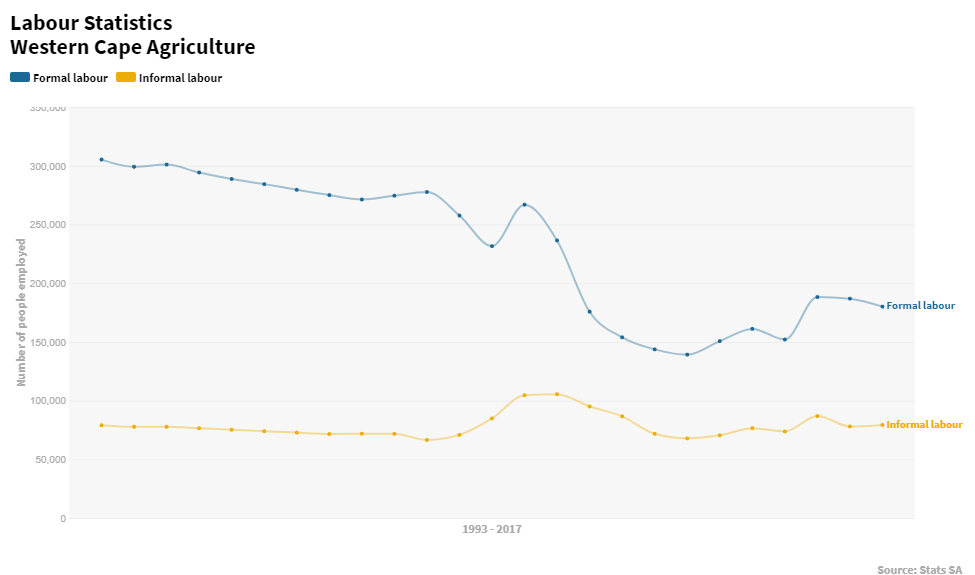

According to the Western Cape Department of Agriculture, the amount of formal workers in the sector has dropped dramatically since the birth of democracy. In 1993, the department recorded 300,000 formal workers in the province. In 2017 this number dropped to 180,000 people. This indicates a staggering 40% loss of employment in the Western Cape alone.

Informal labour figures in the sector have remained fairly consistent over the same period of time, sitting at almost 80,000 people who are employed on an informal basis. The data received from the department only indicates labour force and does not provide detail on the living arrangements of these workers.

Mercia Andrews, director of the Trust for Community Outreach and Education, says her organisation is demanding “a moratorium on evictions” and that they want “greater intervention” from the state when it comes to the evictions of farm workers and farm dwellers. The trust works closely with communities all over the country to educate citizens about their rights to land and to organise and mobilise for a better quality of life for those living in rural areas.

“It’s a contradiction when we are discussing land expropriation without compensation and the state is not intervening when people are being evicted,” says Andrew. “Their rights to possible land and possible security of tenure are being violated all the time”.

According to Andrews land patterns have “hardly shifted” and the Constitution should be changed in order to aid transformation.

“The Western Cape is an interesting example of prime commercial land that has largely remained in white-owned hands… we need a whole reconceptualisation of how land reform and land redistribution should take place,” she says.

Betana says that one of the projects her organisation is undertaking is to get the Witzenberg municipality to build houses specifically for farm workers with the financial backing of land owners. “We’re living in an agricultural area, farm workers will be dismissed or retire, so there needs to be a separate housing list for farm workers. Land owners must come to the table and make a contribution,” she says.

“Some of us just want a bit of land where we can live with our children” she says.

Elizabeth Domingo’s house seen through pear orchards on a farm in Ceres. She and her family are facing eviction by the farm owner. 13 July 2018. Photo: Leila Dougan

Domingo is continuing to fight her eviction because it’s the only house she has ever known. “It’s safe for us, it’s safe for our children, I can walk alone at night at 10 or 11 o’clock, nothing happens to me. But if I go and live in the town I can’t walk outside at 11pm,” she says.

She smiles as she recalls some of her childhood memories on Platvlei farm, eating grapes from the vines that once grew around her house, building sandpits under the plum trees and the time her grandmother built a swimming pool out of stone in the front garden. “You crawl in there and your skin is raw from crawling [over the stones],” she says with a laugh, holding her knees as though the childhood grazes remain.

“Our children also still enjoy it here. If we have to go I’ll miss it,” she says, before adding that the those who own the land also “grew up” in that house. The families of the land workers and land owners knew one another and remained respectful and civil until their relationship broke down due to the eviction case.

“As long as you can work for a farmer, is it fine. But the day you can’t any more, the farmer doesn’t worry about you any more. What did my grandpa get out of this deal? Nothing! We got nothing!” she says.

“So I feel I can get this house. That’s what I feel. They can give me this house.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider